[Updated on 2019-02-14: add ULMFiT and GPT-2.]

[Updated on 2020-02-29: add ALBERT.]

[Updated on 2020-10-25: add RoBERTa.]

[Updated on 2020-12-13: add T5.]

[Updated on 2020-12-30: add GPT-3.]

[Updated on 2021-11-13: add XLNet, BART and ELECTRA; Also updated the Summary section.]

We have seen amazing progress in NLP in 2018. Large-scale pre-trained language modes like OpenAI GPT and BERT have achieved great performance on a variety of language tasks using generic model architectures. The idea is similar to how ImageNet classification pre-training helps many vision tasks (*). Even better than vision classification pre-training, this simple and powerful approach in NLP does not require labeled data for pre-training, allowing us to experiment with increased training scale, up to our very limit.

(*) He et al. (2018) found that pre-training might not be necessary for image segmentation task.

In my previous NLP post on word embedding, the introduced embeddings are not context-specific — they are learned based on word concurrency but not sequential context. So in two sentences, “I am eating an apple” and “I have an Apple phone”, two “apple” words refer to very different things but they would still share the same word embedding vector.

Despite this, early adoption of word embeddings in problem-solving is to use them as additional features for an existing task-specific model and in a way the improvement is bounded.

In this post, we will discuss how various approaches were proposed to make embeddings dependent on context, and to make them easier and cheaper to be applied to downstream tasks in general form.

CoVe

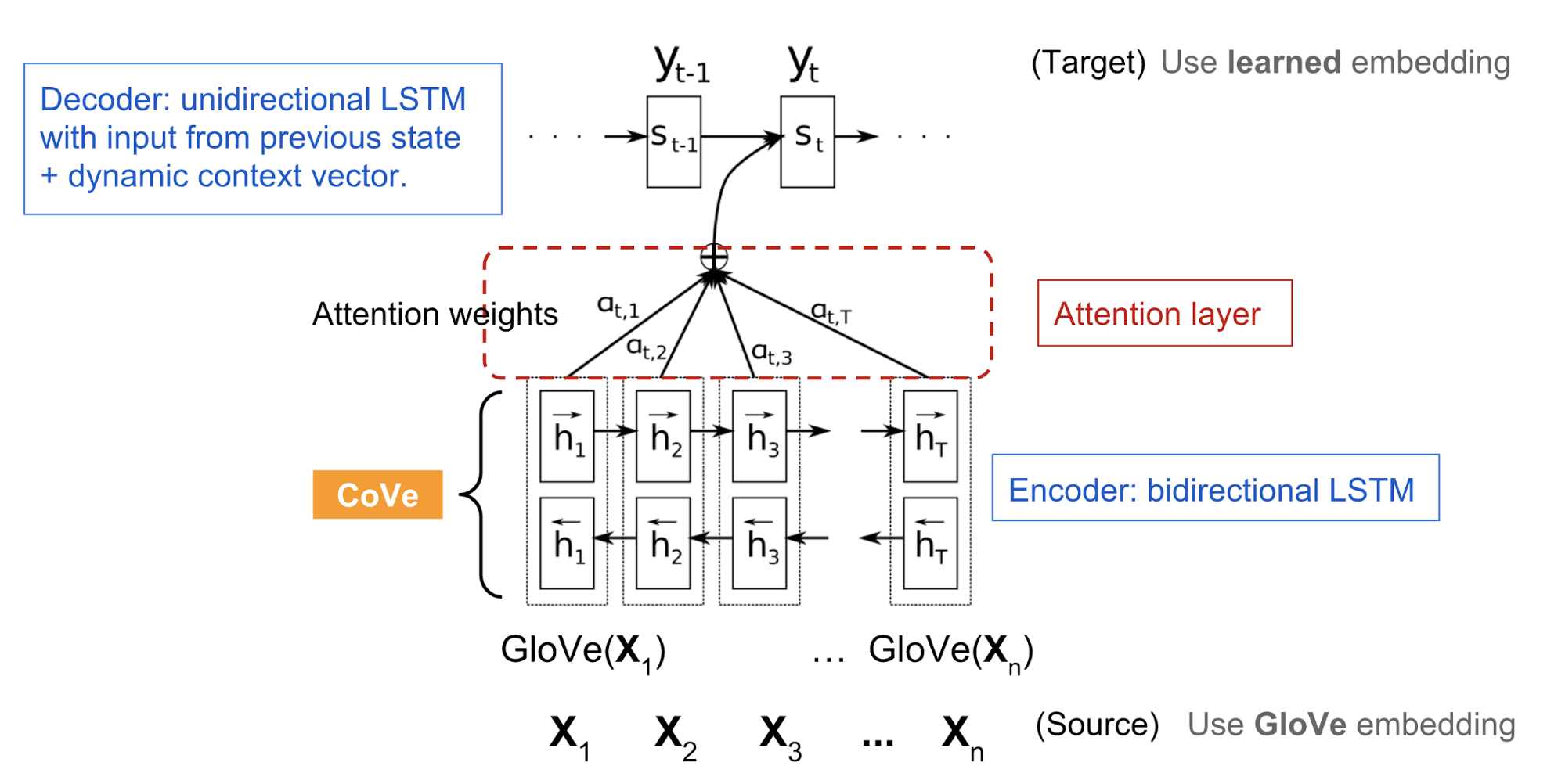

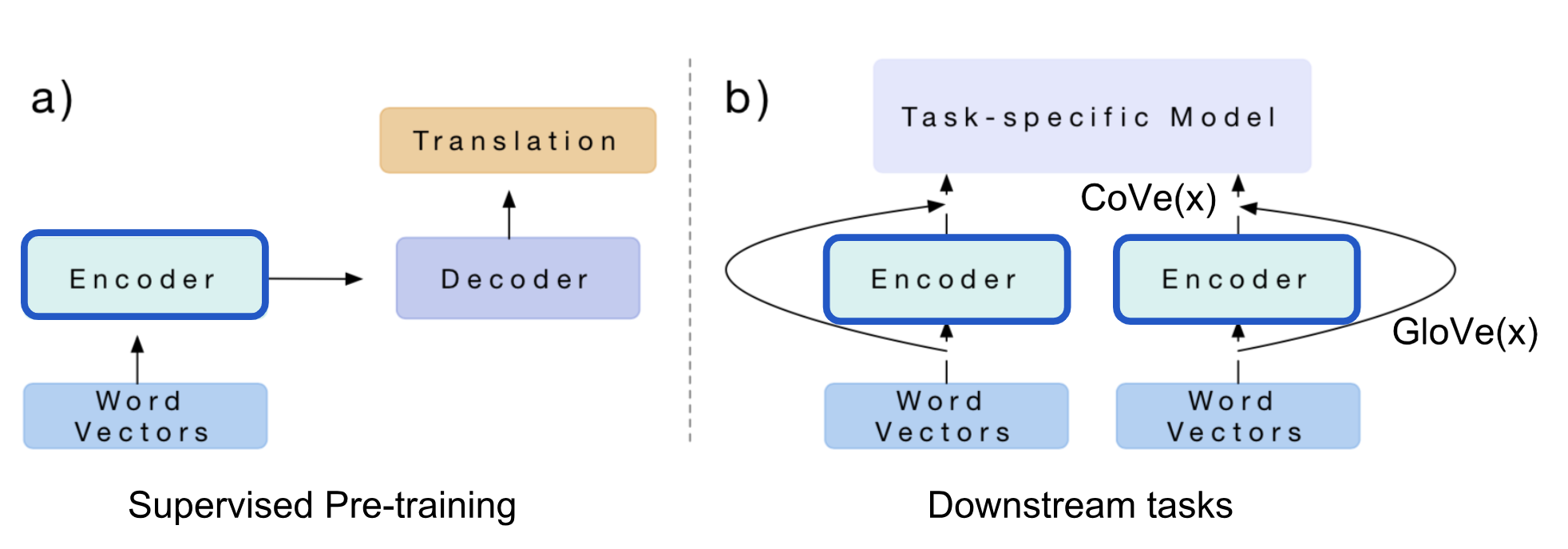

CoVe (McCann et al. 2017), short for Contextual Word Vectors, is a type of word embeddings learned by an encoder in an attentional seq-to-seq machine translation model. Different from traditional word embeddings introduced here, CoVe word representations are functions of the entire input sentence.

NMT Recap

Here the Neural Machine Translation (NMT) model is composed of a standard, two-layer, bidirectional LSTM encoder and an attentional two-layer unidirectional LSTM decoder. It is pre-trained on the English-German translation task. The encoder learns and optimizes the embedding vectors of English words in order to translate them to German. With the intuition that the encoder should capture high-level semantic and syntactic meanings before transforming words into another language, the encoder output is used to provide contextualized word embeddings for various downstream language tasks.

- A sequence of $n$ words in source language (English): $x = [x_1, \dots, x_n]$.

- A sequence of $m$ words in target language (German): $y = [y_1, \dots, y_m]$.

- The GloVe vectors of source words: $\text{GloVe}(x)$.

- Randomly initialized embedding vectors of target words: $z = [z_1, \dots, z_m]$.

- The biLSTM encoder outputs a sequence of hidden states: $h = [h_1, \dots, h_n] = \text{biLSTM}(\text{GloVe}(x))$ and $h_t = [\overrightarrow{h}_t; \overleftarrow{h}_t]$ where the forward LSTM computes $\overrightarrow{h}_t = \text{LSTM}(x_t, \overrightarrow{h}_{t-1})$ and the backward computation gives us $\overleftarrow{h}_t = \text{LSTM}(x_t, \overleftarrow{h}_{t-1})$.

- The attentional decoder outputs a distribution over words: $p(y_t \mid H, y_1, \dots, y_{t-1})$ where $H$ is a stack of hidden states $\{h\}$ along the time dimension:

Use CoVe in Downstream Tasks

The hidden states of NMT encoder are defined as context vectors for other language tasks:

The paper proposed to use the concatenation of GloVe and CoVe for question-answering and classification tasks. GloVe learns from the ratios of global word co-occurrences, so it has no sentence context, while CoVe is generated by processing text sequences is able to capture the contextual information.

Given a downstream task, we first generate the concatenation of GloVe + CoVe vectors of input words and then feed them into the task-specific models as additional features.

Summary: The limitation of CoVe is obvious: (1) pre-training is bounded by available datasets on the supervised translation task; (2) the contribution of CoVe to the final performance is constrained by the task-specific model architecture.

In the following sections, we will see that ELMo overcomes issue (1) by unsupervised pre-training and OpenAI GPT & BERT further overcome both problems by unsupervised pre-training + using generative model architecture for different downstream tasks.

ELMo

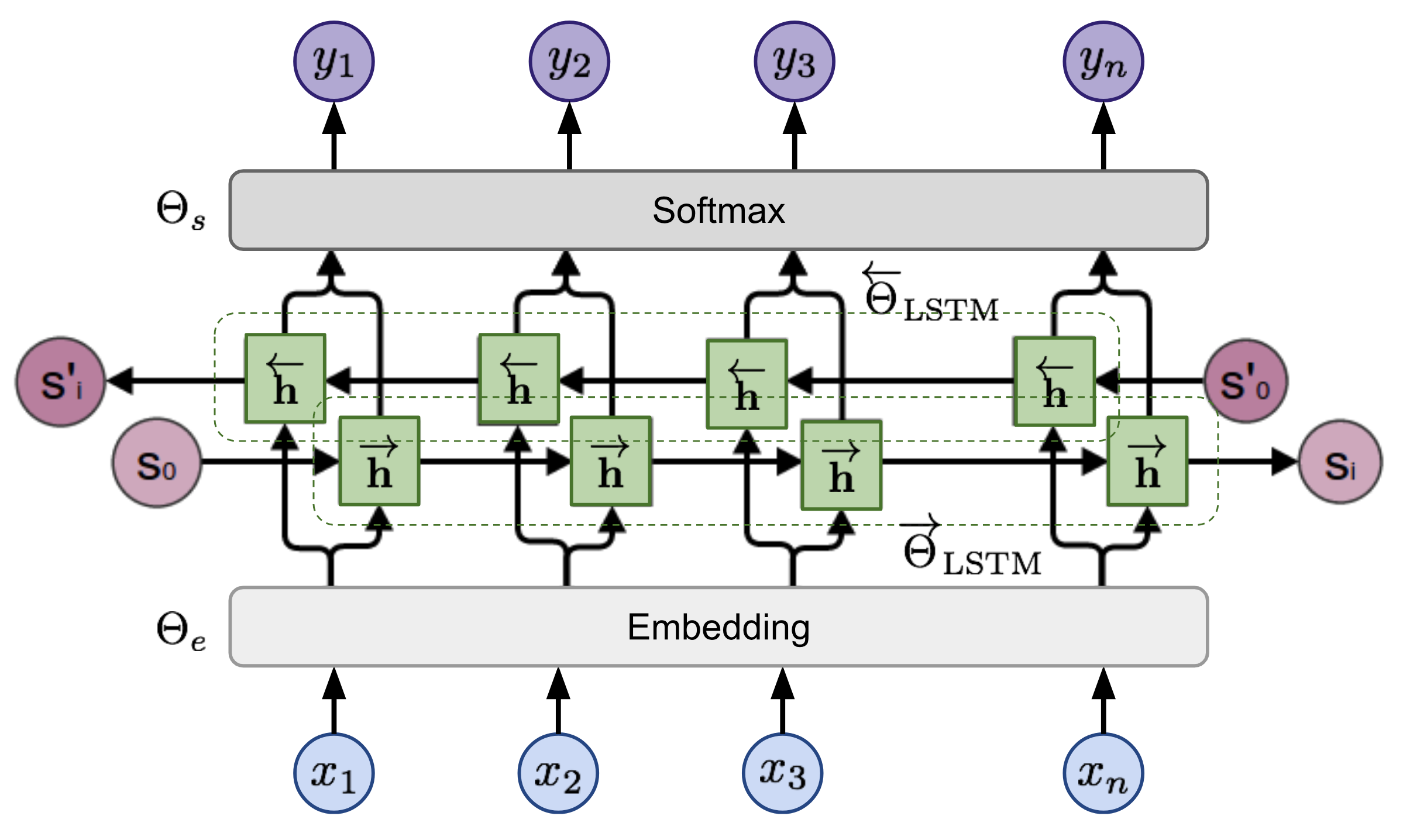

ELMo, short for Embeddings from Language Model (Peters, et al, 2018) learns contextualized word representation by pre-training a language model in an unsupervised way.

Bidirectional Language Model

The bidirectional Language Model (biLM) is the foundation for ELMo. While the input is a sequence of $n$ tokens, $(x_1, \dots, x_n)$, the language model learns to predict the probability of next token given the history.

In the forward pass, the history contains words before the target token,

In the backward pass, the history contains words after the target token,

The predictions in both directions are modeled by multi-layer LSTMs with hidden states $\overrightarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,\ell}$ and $\overleftarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,\ell}$ for input token $x_i$ at the layer level $\ell=1,\dots,L$. The final layer’s hidden state $\mathbf{h}_{i,L} = [\overrightarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,L}; \overleftarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,L}]$ is used to output the probabilities over tokens after softmax normalization. They share the embedding layer and the softmax layer, parameterized by $\Theta_e$ and $\Theta_s$ respectively.

The model is trained to minimize the negative log likelihood (= maximize the log likelihood for true words) in both directions:

ELMo Representations

On top of a $L$-layer biLM, ELMo stacks all the hidden states across layers together by learning a task-specific linear combination. The hidden state representation for the token $x_i$ contains $2L+1$ vectors:

where $\mathbf{h}_{0, \ell}$ is the embedding layer output and $\mathbf{h}_{i, \ell} = [\overrightarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,\ell}; \overleftarrow{\mathbf{h}}_{i,\ell}]$.

The weights, $\mathbf{s}^\text{task}$, in the linear combination are learned for each end task and normalized by softmax. The scaling factor $\gamma^\text{task}$ is used to correct the misalignment between the distribution of biLM hidden states and the distribution of task specific representations.

To evaluate what kind of information is captured by hidden states across different layers, ELMo is applied on semantic-intensive and syntax-intensive tasks respectively using representations in different layers of biLM:

- Semantic task: The word sense disambiguation (WSD) task emphasizes the meaning of a word given a context. The biLM top layer is better at this task than the first layer.

- Syntax task: The part-of-speech (POS) tagging task aims to infer the grammatical role of a word in one sentence. A higher accuracy can be achieved by using the biLM first layer than the top layer.

The comparison study indicates that syntactic information is better represented at lower layers while semantic information is captured by higher layers. Because different layers tend to carry different type of information, stacking them together helps.

Use ELMo in Downstream Tasks

Similar to how CoVe can help different downstream tasks, ELMo embedding vectors are included in the input or lower levels of task-specific models. Moreover, for some tasks (i.e., SNLI and SQuAD, but not SRL), adding them into the output level helps too.

The improvements brought up by ELMo are largest for tasks with a small supervised dataset. With ELMo, we can also achieve similar performance with much less labeled data.

Summary: The language model pre-training is unsupervised and theoretically the pre-training can be scaled up as much as possible since the unlabeled text corpora are abundant. However, it still has the dependency on task-customized models and thus the improvement is only incremental, while searching for a good model architecture for every task remains non-trivial.

Cross-View Training

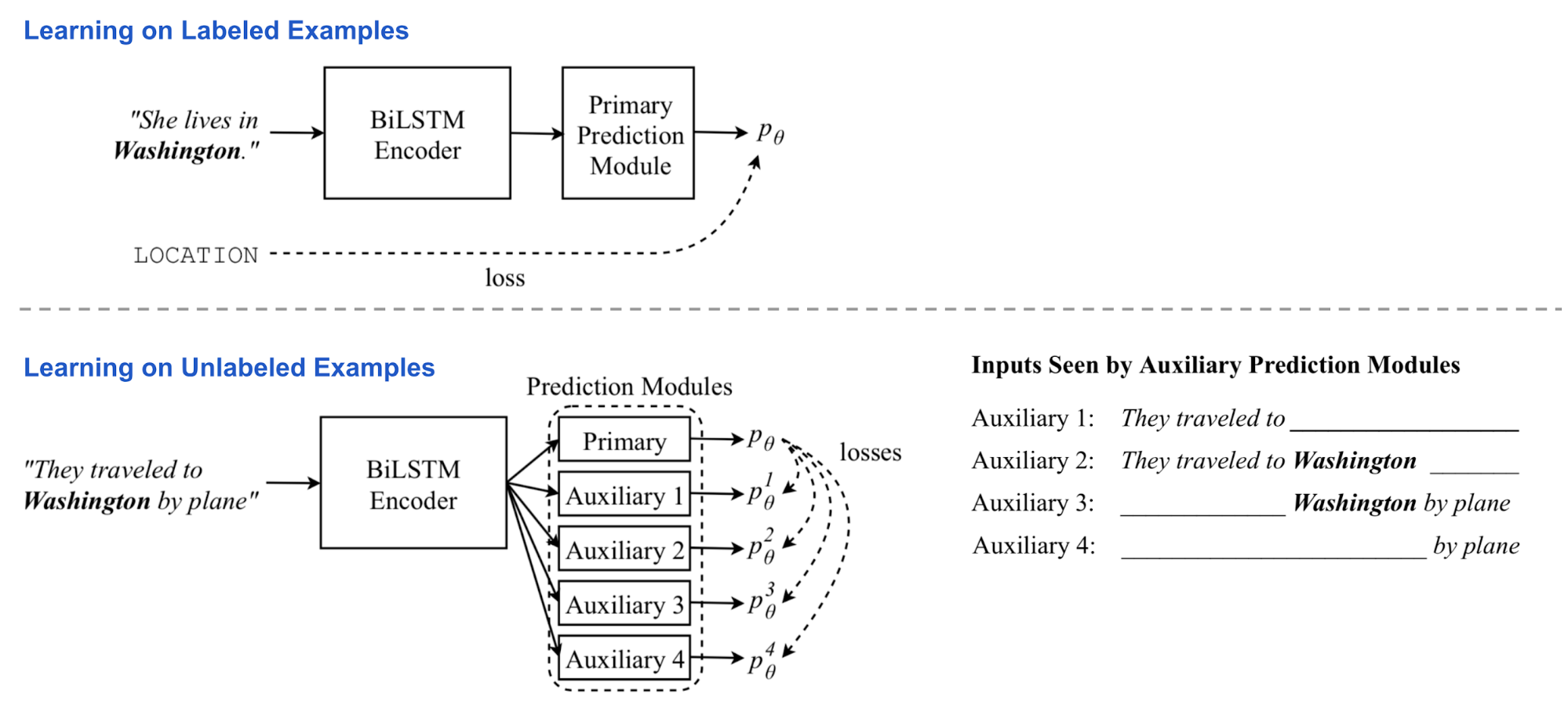

In ELMo the unsupervised pre-training and task-specific learning happen for two independent models in two separate training stages. Cross-View Training (abbr. CVT; Clark et al., 2018) combines them into one unified semi-supervised learning procedure where the representation of a biLSTM encoder is improved by both supervised learning with labeled data and unsupervised learning with unlabeled data on auxiliary tasks.

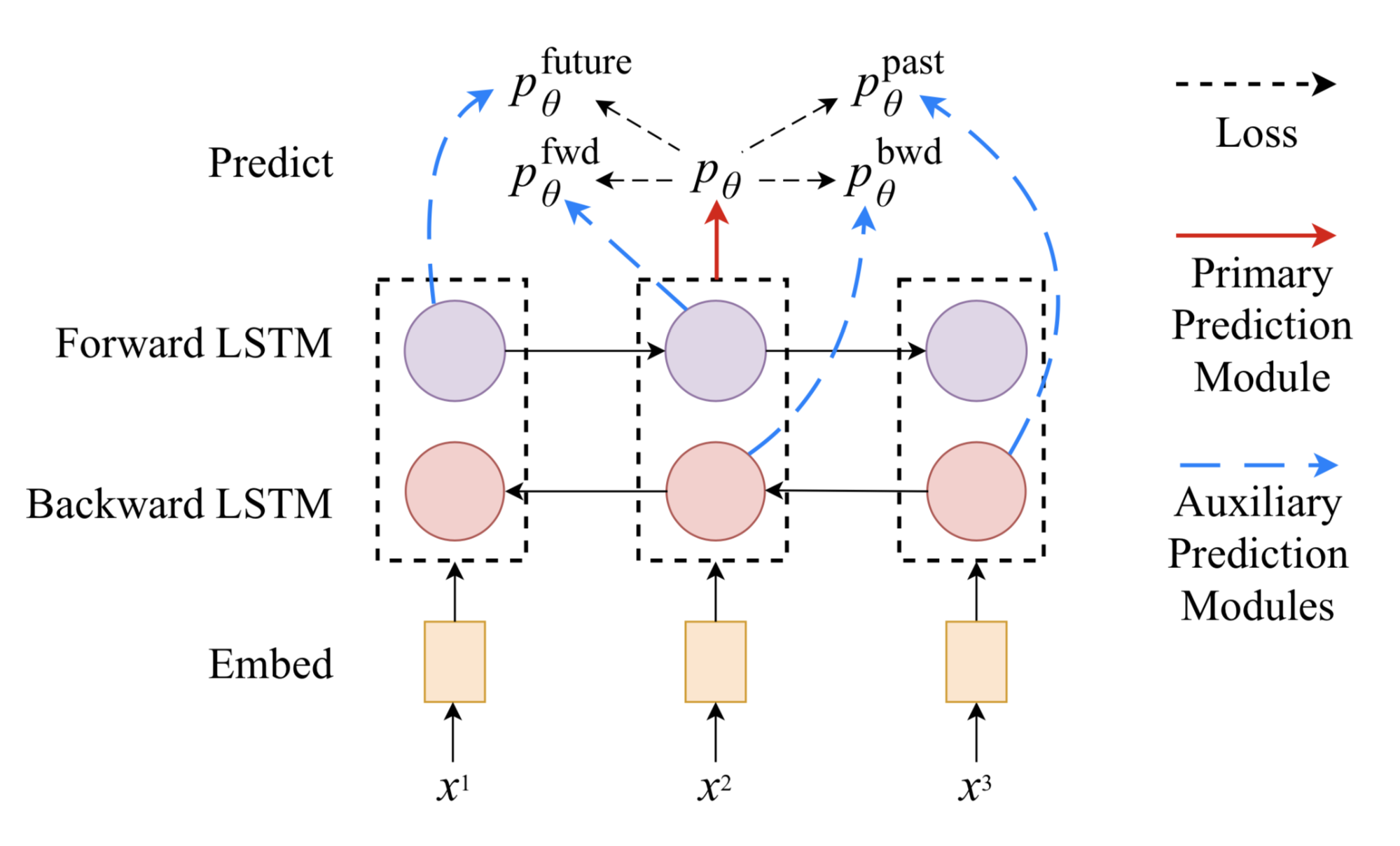

Model Architecture

The model consists of a two-layer bidirectional LSTM encoder and a primary prediction module. During training, the model is fed with labeled and unlabeled data batches alternatively.

- On labeled examples, all the model parameters are updated by standard supervised learning. The loss is the standard cross entropy.

- On unlabeled examples, the primary prediction module still can produce a “soft” target, even though we cannot know exactly how accurate they are. In a couple of auxiliary tasks, the predictor only sees and processes a restricted view of the input, such as only using encoder hidden state representation in one direction. The auxiliary task outputs are expected to match the primary prediction target for a full view of input.

In this way, the encoder is forced to distill the knowledge of the full context into partial representation. At this stage, the biLSTM encoder is backpropagated but the primary prediction module is fixed. The loss is to minimize the distance between auxiliary and primary predictions.

Multi-Task Learning

When training for multiple tasks simultaneously, CVT adds several extra primary prediction models for additional tasks. They all share the same sentence representation encoder. During supervised training, once one task is randomly selected, parameters in its corresponding predictor and the representation encoder are updated. With unlabeled data samples, the encoder is optimized jointly across all the tasks by minimizing the differences between auxiliary outputs and primary prediction for every task.

The multi-task learning encourages better generality of representation and in the meantime produces a nice side-product: all-tasks-labeled examples from unlabeled data. They are precious data labels considering that cross-task labels are useful but fairly rare.

Use CVT in Downstream Tasks

Theoretically the primary prediction module can take any form, generic or task-specific design. The examples presented in the CVT paper include both cases.

In sequential tagging tasks (classification for every token) like NER or POS tagging, the predictor module contains two fully connected layers and a softmax layer on the output to produce a probability distribution over class labels. For each token $\mathbf{x}_i$, we take the corresponding hidden states in two layers, $\mathbf{h}_1^{(i)}$ and $\mathbf{h}_2^{(i)}$:

The auxiliary tasks are only fed with forward or backward LSTM state in the first layer. Because they only observe partial context, either on the left or right, they have to learn like a language model, trying to predict the next token given the context. The fwd and bwd auxiliary tasks only take one direction. The future and past tasks take one step further in forward and backward direction, respectively.

Note that if the primary prediction module has dropout, the dropout layer works as usual when training with labeled data, but it is not applied when generating “soft” target for auxiliary tasks during training with unlabeled data.

In the machine translation task, the primary prediction module is replaced with a standard unidirectional LSTM decoder with attention. There are two auxiliary tasks: (1) apply dropout on the attention weight vector by randomly zeroing out some values; (2) predict the future word in the target sequence. The primary prediction for auxiliary tasks to match is the best predicted target sequence produced by running the fixed primary decoder on the input sequence with beam search.

ULMFiT

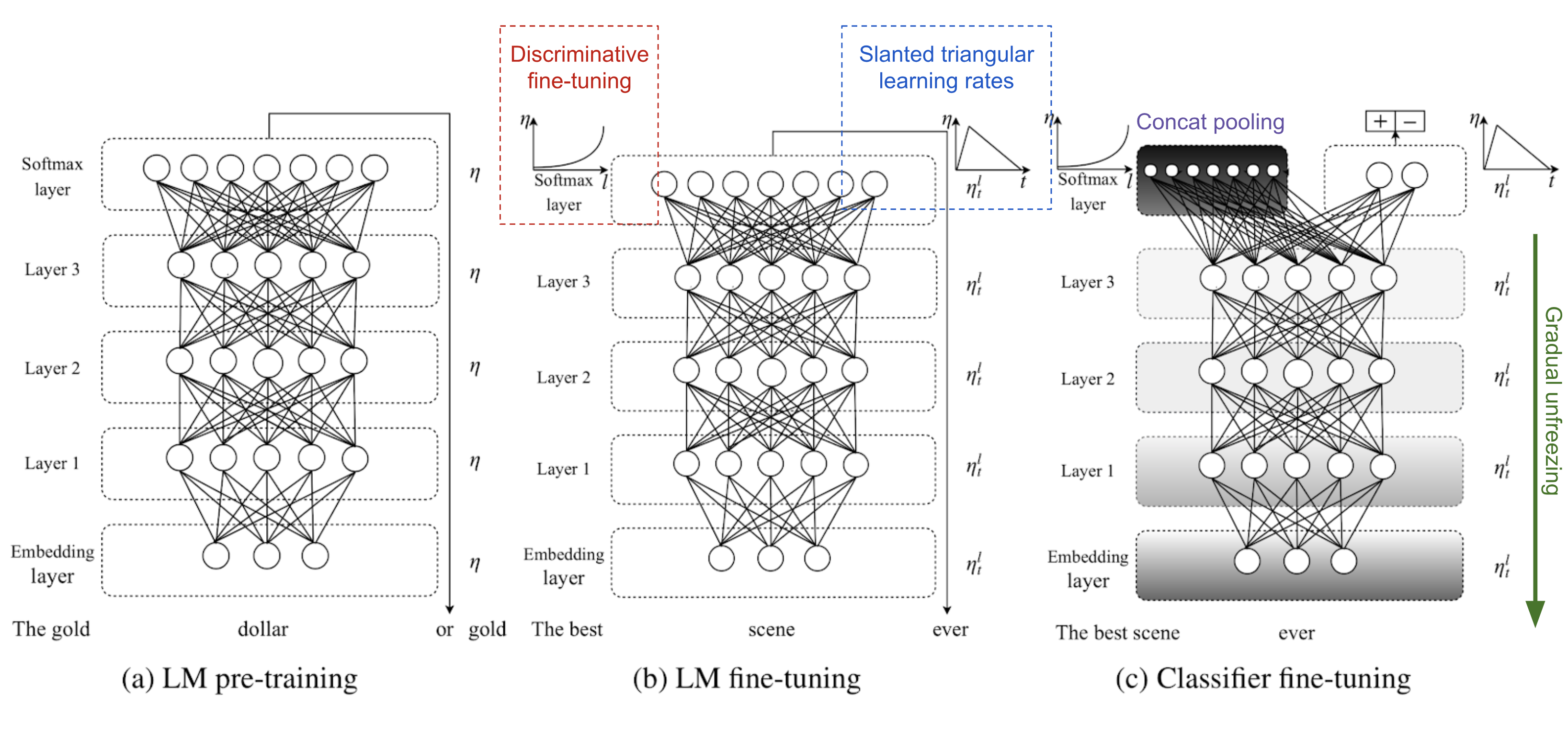

The idea of using generative pretrained LM + task-specific fine-tuning was first explored in ULMFiT (Howard & Ruder, 2018), directly motivated by the success of using ImageNet pre-training for computer vision tasks. The base model is AWD-LSTM.

ULMFiT follows three steps to achieve good transfer learning results on downstream language classification tasks:

-

General LM pre-training: on Wikipedia text.

-

Target task LM fine-tuning: ULMFiT proposed two training techniques for stabilizing the fine-tuning process. See below.

-

Discriminative fine-tuning is motivated by the fact that different layers of LM capture different types of information (see discussion above). ULMFiT proposed to tune each layer with different learning rates, $\{\eta^1, \dots, \eta^\ell, \dots, \eta^L\}$, where $\eta$ is the base learning rate for the first layer, $\eta^\ell$ is for the $\ell$-th layer and there are $L$ layers in total.

-

Slanted triangular learning rates (STLR) refer to a special learning rate scheduling that first linearly increases the learning rate and then linearly decays it. The increase stage is short so that the model can converge to a parameter space suitable for the task fast, while the decay period is long allowing for better fine-tuning.

- Target task classifier fine-tuning: The pretrained LM is augmented with two standard feed-forward layers and a softmax normalization at the end to predict a target label distribution.

-

Concat pooling extracts max-polling and mean-pooling over the history of hidden states and concatenates them with the final hidden state.

-

Gradual unfreezing helps to avoid catastrophic forgetting by gradually unfreezing the model layers starting from the last one. First the last layer is unfrozen and fine-tuned for one epoch. Then the next lower layer is unfrozen. This process is repeated until all the layers are tuned.

GPT

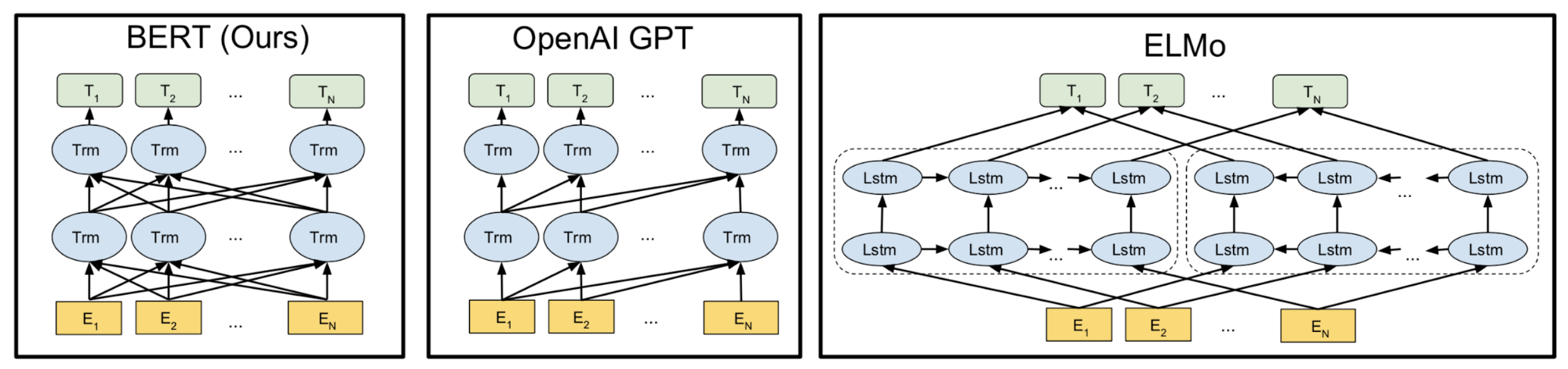

Following the similar idea of ELMo, OpenAI GPT, short for Generative Pre-training Transformer (Radford et al., 2018), expands the unsupervised language model to a much larger scale by training on a giant collection of free text corpora. Despite of the similarity, GPT has two major differences from ELMo.

- The model architectures are different: ELMo uses a shallow concatenation of independently trained left-to-right and right-to-left multi-layer LSTMs, while GPT is a multi-layer transformer decoder.

- The use of contextualized embeddings in downstream tasks are different: ELMo feeds embeddings into models customized for specific tasks as additional features, while GPT fine-tunes the same base model for all end tasks.

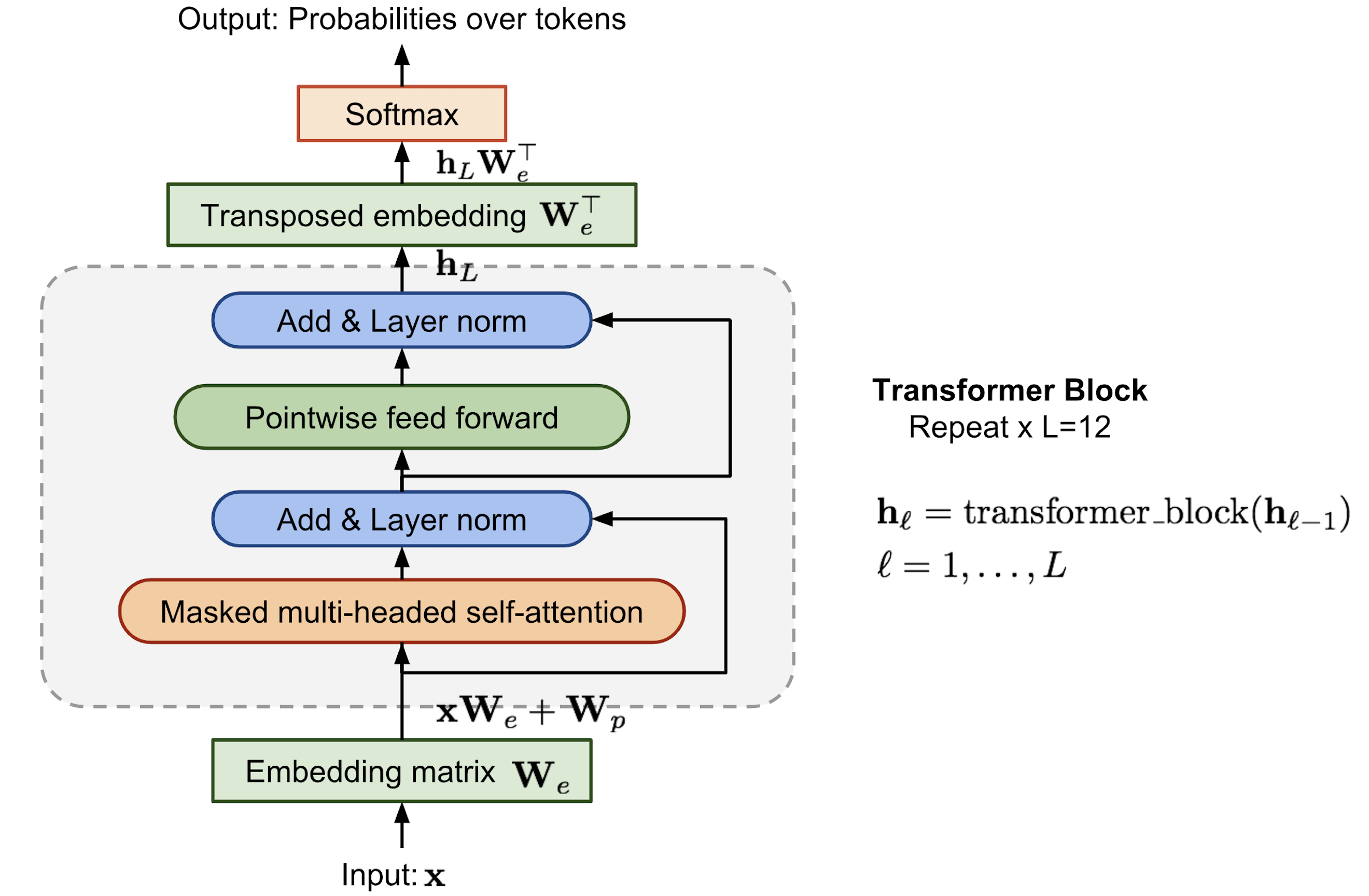

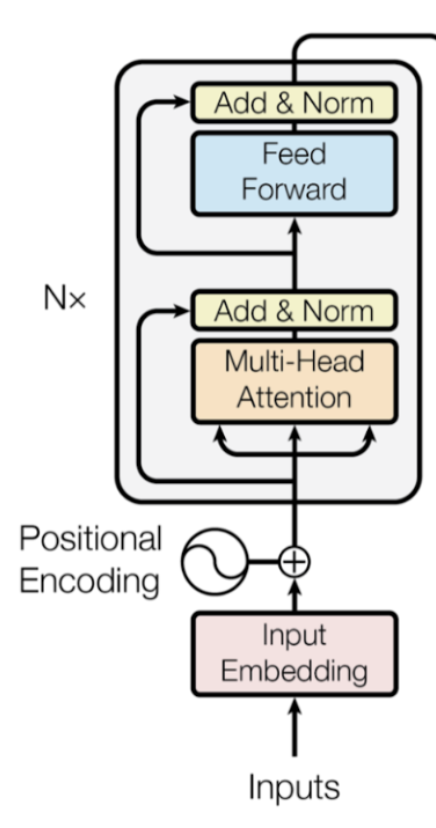

Transformer Decoder as Language Model

Compared to the original transformer architecture, the transformer decoder model discards the encoder part, so there is only one single input sentence rather than two separate source and target sequences.

This model applies multiple transformer blocks over the embeddings of input sequences. Each block contains a masked multi-headed self-attention layer and a pointwise feed-forward layer. The final output produces a distribution over target tokens after softmax normalization.

The loss is the negative log-likelihood, same as ELMo, but without backward computation. Let’s say, the context window of the size $k$ is located before the target word and the loss would look like:

Byte Pair Encoding

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) is used to encode the input sequences. BPE was originally proposed as a data compression algorithm in 1990s and then was adopted to solve the open-vocabulary issue in machine translation, as we can easily run into rare and unknown words when translating into a new language. Motivated by the intuition that rare and unknown words can often be decomposed into multiple subwords, BPE finds the best word segmentation by iteratively and greedily merging frequent pairs of characters.

Supervised Fine-Tuning

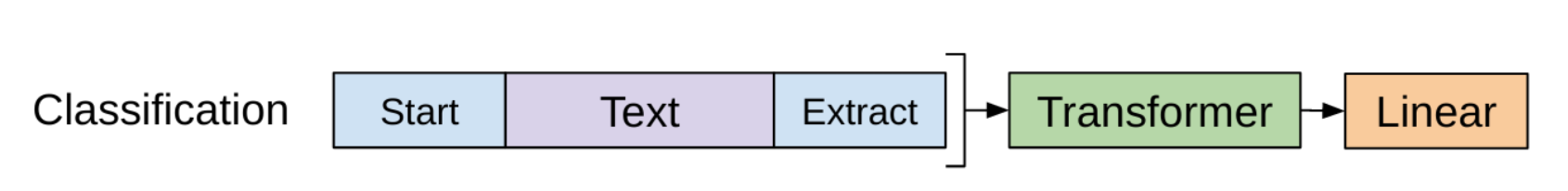

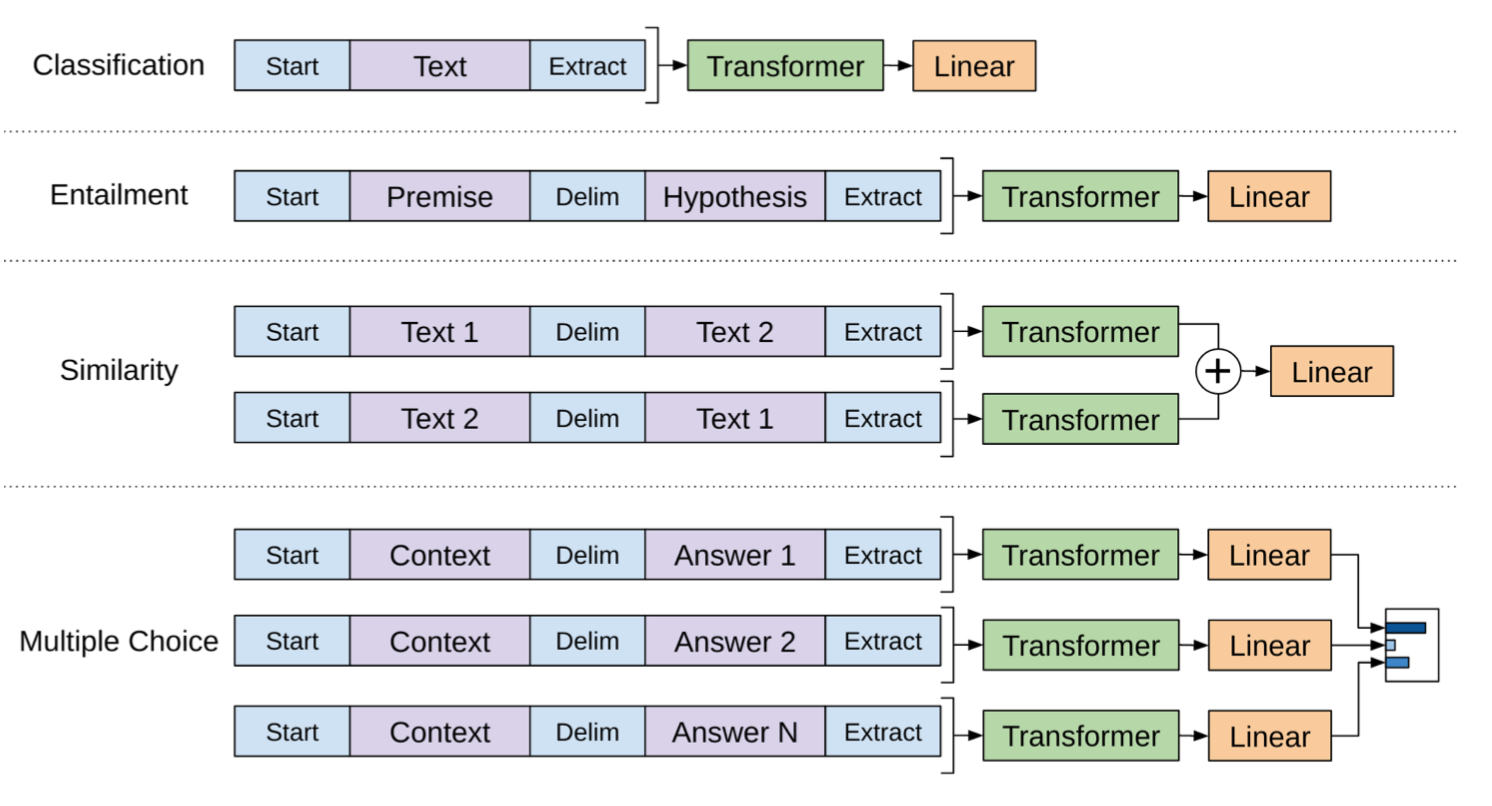

The most substantial upgrade that OpenAI GPT proposed is to get rid of the task-specific model and use the pre-trained language model directly!

Let’s take classification as an example. Say, in the labeled dataset, each input has $n$ tokens, $\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \dots, x_n)$, and one label $y$. GPT first processes the input sequence $\mathbf{x}$ through the pre-trained transformer decoder and the last layer output for the last token $x_n$ is $\mathbf{h}_L^{(n)}$. Then with only one new trainable weight matrix $\mathbf{W}_y$, it can predict a distribution over class labels.

The loss is to minimize the negative log-likelihood for true labels. In addition, adding the LM loss as an auxiliary loss is found to be beneficial, because:

- (1) it helps accelerate convergence during training and

- (2) it is expected to improve the generalization of the supervised model.

With similar designs, no customized model structure is needed for other end tasks (see Fig. 7). If the task input contains multiple sentences, a special delimiter token ($) is added between each pair of sentences. The embedding for this delimiter token is a new parameter we need to learn, but it should be pretty minimal.

For the sentence similarity task, because the ordering does not matter, both orderings are included. For the multiple choice task, the context is paired with every answer candidate.

Summary: It is super neat and encouraging to see that such a general framework is capable to beat SOTA on most language tasks at that time (June 2018). At the first stage, generative pre-training of a language model can absorb as much free text as possible. Then at the second stage, the model is fine-tuned on specific tasks with a small labeled dataset and a minimal set of new parameters to learn.

One limitation of GPT is its uni-directional nature — the model is only trained to predict the future left-to-right context.

BERT

BERT, short for Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (Devlin, et al., 2019) is a direct descendant to GPT: train a large language model on free text and then fine-tune on specific tasks without customized network architectures.

Compared to GPT, the largest difference and improvement of BERT is to make training bi-directional. The model learns to predict both context on the left and right. The paper according to the ablation study claimed that:

“bidirectional nature of our model is the single most important new contribution”

Pre-training Tasks

The model architecture of BERT is a multi-layer bidirectional Transformer encoder.

To encourage the bi-directional prediction and sentence-level understanding, BERT is trained with two tasks instead of the basic language task (that is, to predict the next token given context).

*Task 1: Mask language model (MLM)

From Wikipedia: “A cloze test (also cloze deletion test) is an exercise, test, or assessment consisting of a portion of language with certain items, words, or signs removed (cloze text), where the participant is asked to replace the missing language item. … The exercise was first described by W.L. Taylor in 1953.”

It is unsurprising to believe that a representation that learns the context around a word rather than just after the word is able to better capture its meaning, both syntactically and semantically. BERT encourages the model to do so by training on the “mask language model” task:

- Randomly mask 15% of tokens in each sequence. Because if we only replace masked tokens with a special placeholder

[MASK], the special token would never be encountered during fine-tuning. Hence, BERT employed several heuristic tricks:- (a) with 80% probability, replace the chosen words with

[MASK]; - (b) with 10% probability, replace with a random word;

- (c) with 10% probability, keep it the same.

- (a) with 80% probability, replace the chosen words with

- The model only predicts the missing words, but it has no information on which words have been replaced or which words should be predicted. The output size is only 15% of the input size.

Task 2: Next sentence prediction

Motivated by the fact that many downstream tasks involve the understanding of relationships between sentences (i.e., QA, NLI), BERT added another auxiliary task on training a binary classifier for telling whether one sentence is the next sentence of the other:

- Sample sentence pairs (A, B) so that:

- (a) 50% of the time, B follows A;

- (b) 50% of the time, B does not follow A.

- The model processes both sentences and output a binary label indicating whether B is the next sentence of A.

The training data for both auxiliary tasks above can be trivially generated from any monolingual corpus. Hence the scale of training is unbounded. The training loss is the sum of the mean masked LM likelihood and mean next sentence prediction likelihood.

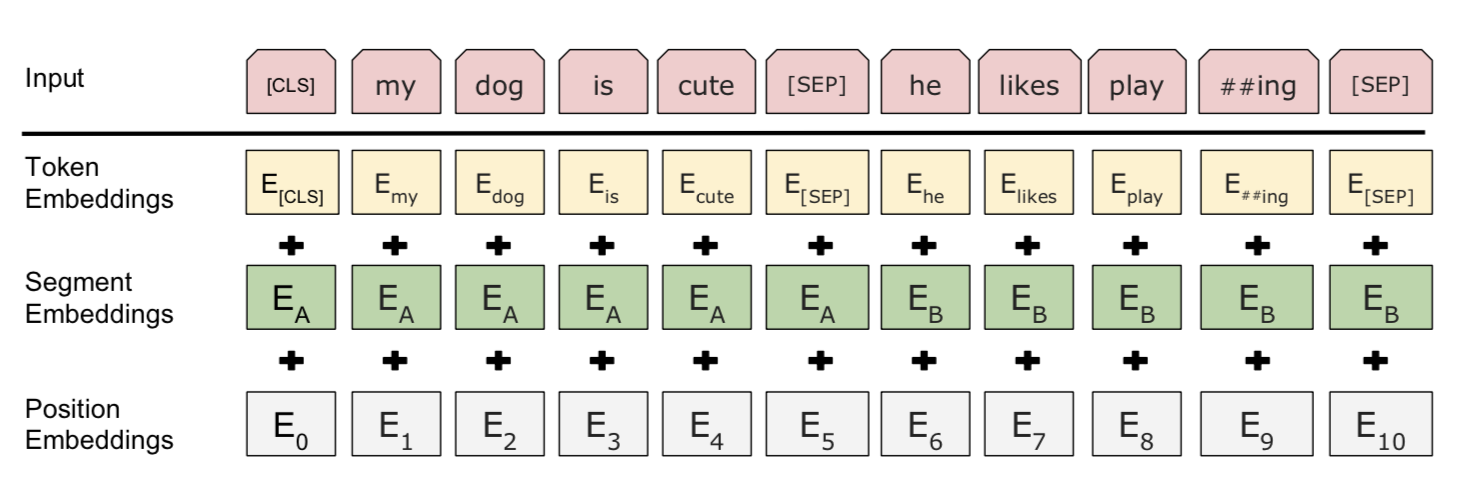

Input Embedding

The input embedding is the sum of three parts:

- WordPiece tokenization embeddings: The WordPiece model was originally proposed for Japanese or Korean segmentation problem. Instead of using naturally split English word, they can be further divided into smaller sub-word units so that it is more effective to handle rare or unknown words. Please read linked papers for the optimal way to split words if interested.

- Segment embeddings: If the input contains two sentences, they have sentence A embeddings and sentence B embeddings respectively and they are separated by a special character

[SEP]; Only sentence A embeddings are used if the input only contains one sentence. - Position embeddings: Positional embeddings are learned rather than hard-coded.

Note that the first token is always forced to be [CLS] — a placeholder that will be used later for prediction in downstream tasks.

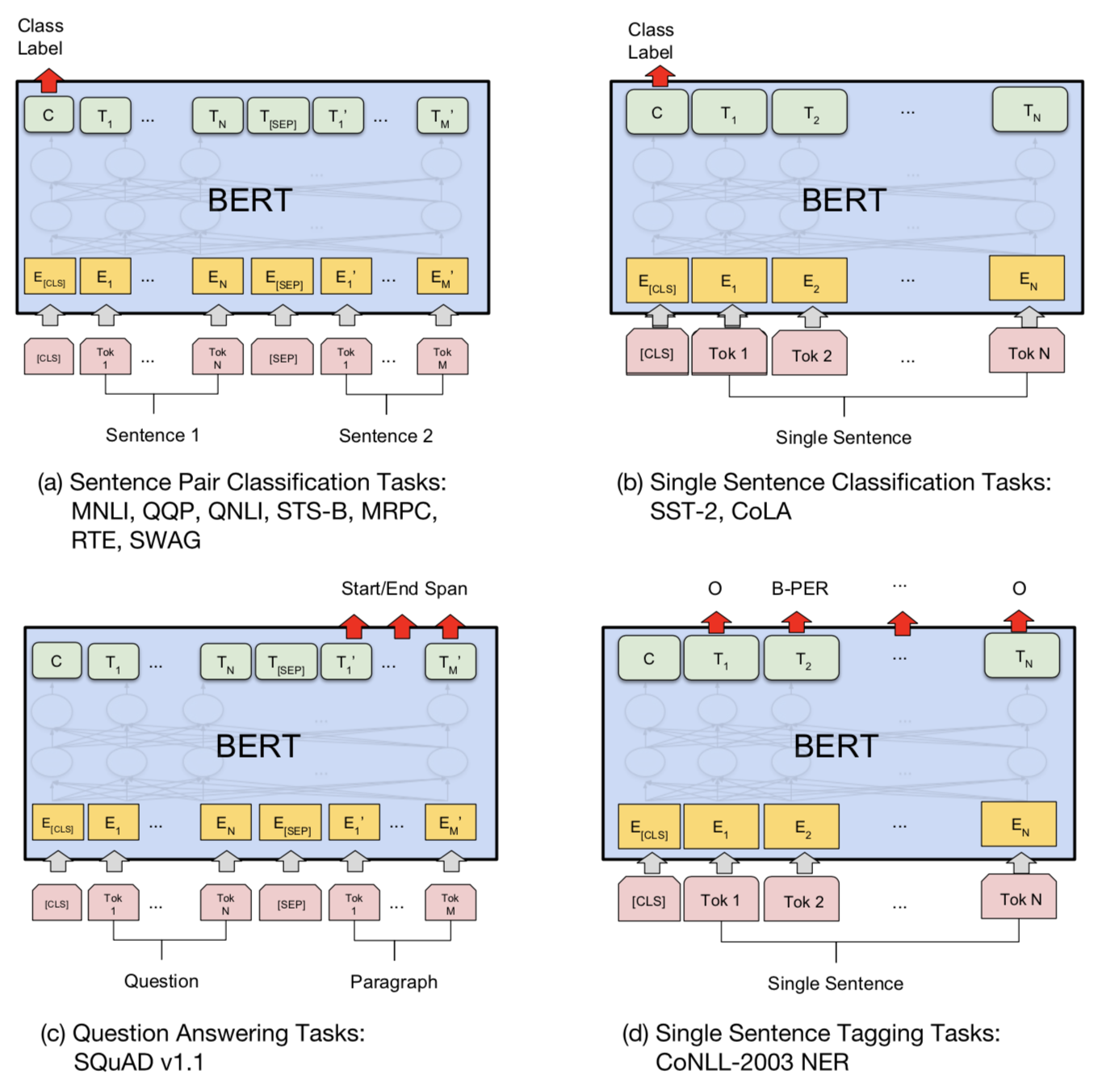

Use BERT in Downstream Tasks

BERT fine-tuning requires only a few new parameters added, just like OpenAI GPT.

For classification tasks, we get the prediction by taking the final hidden state of the special first token [CLS], $\mathbf{h}^\text{[CLS]}_L$, and multiplying it with a small weight matrix, $\text{softmax}(\mathbf{h}^\text{[CLS]}_L \mathbf{W}_\text{cls})$.

For QA tasks like SQuAD, we need to predict the text span in the given paragraph for an given question. BERT predicts two probability distributions of every token, being the start and the end of the text span. Only two new small matrices, $\mathbf{W}_\text{s}$ and $\mathbf{W}_\text{e}$, are newly learned during fine-tuning and $\text{softmax}(\mathbf{h}^\text{(i)}_L \mathbf{W}_\text{s})$ and $\text{softmax}(\mathbf{h}^\text{(i)}_L \mathbf{W}_\text{e})$ define two probability distributions.

Overall the add-on part for end task fine-tuning is very minimal — one or two weight matrices to convert the Transform hidden states to an interpretable format. Check the paper for implementation details for other cases.

A summary table compares differences between fine-tuning of OpenAI GPT and BERT.

| | OpenAI GPT | BERT |

| Special char | [SEP] and [CLS] are only introduced at fine-tuning stage. | [SEP] and [CLS] and sentence A/B embeddings are learned at the pre-training stage. |

| Training process | 1M steps, batch size 32k words. | 1M steps, batch size 128k words. |

| Fine-tuning | lr = 5e-5 for all fine-tuning tasks. | Use task-specific lr for fine-tuning. |

ALBERT

ALBERT (Lan, et al. 2019), short for A Lite BERT, is a light-weighted version of BERT model. An ALBERT model can be trained 1.7x faster with 18x fewer parameters, compared to a BERT model of similar configuration. ALBERT incorporates three changes as follows: the first two help reduce parameters and memory consumption and hence speed up the training speed, while the third one proposes a more chanllenging training task to replace the next sentence prediction (NSP) objective.

Factorized Embedding Parameterization

In BERT, the WordPiece tokenization embedding size $E$ is configured to be the same as the hidden state size $H$. That is saying, if we want to increase the model size (larger $H$), we need to learn a larger tokenization embedding too, which is expensive because it depends on the vocabulary size ($V$).

Conceptually, because the tokenization embedding is expected to learn context-independent representation and the hidden states are context-dependent, it makes sense to separate the size of the hidden layers from the size of vocabulary embedding. Using factorized embedding parameterization, the large vocabulary embedding matrix of size $V \times H$ is decomposed into two small matrices of size $V \times E$ and $E \times H$. Given $H \gt E$ or even $H \gg E$, factorization can result in significant parameter reduction.

Cross-layer Parameter Sharing

Parameter sharing across layers can happen in many ways: (a) only share feed-forward part; (b) only share attention parameters; or (c) share all the parameters. This technique reduces the number of parameters by a ton and does not damage the performance too much.

Sentence-Order Prediction (SOP)

Interestingly, the next sentence prediction (NSP) task of BERT turned out to be too easy. ALBERT instead adopted a sentence-order prediction (SOP) self-supervised loss,

- Positive sample: two consecutive segments from the same document.

- Negative sample: same as above, but the segment order is switched.

For the NSP task, the model can make reasonable predictions if it is able to detect topics when A and B are from different contexts. In comparison, SOP is harder as it requires the model to fully understand the coherence and ordering between segments.

GPT-2

The OpenAI GPT-2 language model is a direct successor to GPT. GPT-2 has 1.5B parameters, 10x more than the original GPT, and it achieves SOTA results on 7 out of 8 tested language modeling datasets in a zero-shot transfer setting without any task-specific fine-tuning. The pre-training dataset contains 8 million Web pages collected by crawling qualified outbound links from Reddit. Large improvements by OpenAI GPT-2 are specially noticeable on small datasets and datasets used for measuring long-term dependency.

Zero-Shot Transfer

The pre-training task for GPT-2 is solely language modeling. All the downstream language tasks are framed as predicting conditional probabilities and there is no task-specific fine-tuning.

- Text generation is straightforward using LM.

- Machine translation task, for example, English to Chinese, is induced by conditioning LM on pairs of “English sentence = Chinese sentence” and “the target English sentence =” at the end.

- For example, the conditional probability to predict might look like:

P(? | I like green apples. = 我喜欢绿苹果。 A cat meows at him. = 一只猫对他喵。It is raining cats and dogs. =")

- For example, the conditional probability to predict might look like:

- QA task is formatted similar to translation with pairs of questions and answers in the context.

- Summarization task is induced by adding

TL;DR:after the articles in the context.

BPE on Byte Sequences

Same as the original GPT, GPT-2 uses BPE but on UTF-8 byte sequences. Each byte can represent 256 different values in 8 bits, while UTF-8 can use up to 4 bytes for one character, supporting up to $2^{31}$ characters in total. Therefore, with byte sequence representation we only need a vocabulary of size 256 and do not need to worry about pre-processing, tokenization, etc. Despite of the benefit, current byte-level LMs still have non-negligible performance gap with the SOTA word-level LMs.

BPE merges frequently co-occurred byte pairs in a greedy manner. To prevent it from generating multiple versions of common words (i.e. dog., dog! and dog? for the word dog), GPT-2 prevents BPE from merging characters across categories (thus dog would not be merged with punctuations like ., ! and ?). This tricks help increase the quality of the final byte segmentation.

Using the byte sequence representation, GPT-2 is able to assign a probability to any Unicode string, regardless of any pre-processing steps.

Model Modifications

Compared to GPT, other than having many more transformer layers and parameters, GPT-2 incorporates only a few architecture modifications:

- Layer normalization was moved to the input of each sub-block, similar to a residual unit of type “building block” (differently from the original type “bottleneck”, it has batch normalization applied before weight layers).

- An additional layer normalization was added after the final self-attention block.

- A modified initialization was constructed as a function of the model depth.

- The weights of residual layers were initially scaled by a factor of $1/ \sqrt{N}$ where N is the number of residual layers.

- Use larger vocabulary size and context size.

RoBERTa

RoBERTa (short for Robustly optimized BERT approach; Liu, et al. 2019) refers to a new receipt for training BERT to achieve better results, as they found that the original BERT model is significantly undertrained. The receipt contains the following learnings:

- Train for longer with bigger batch size.

- Remove the next sentence prediction (NSP) task.

- Use longer sequences in training data format. The paper found that using individual sentences as inputs hurts downstream performance. Instead we should use multiple sentences sampled contiguously to form longer segments.

- Change the masking pattern dynamically. The original BERT applies masking once during the data preprocessing stage, resulting in a static mask across training epochs. RoBERTa applies masks in 10 different ways across 40 epochs.

RoBERTa also added a new dataset CommonCrawl News and further confirmed that pretraining with more data helps improve the performance on downstream tasks. It was trained with the BPE on byte sequences, same as in GPT-2. They also found that choices of hyperparameters have a big impact on the model performance.

T5

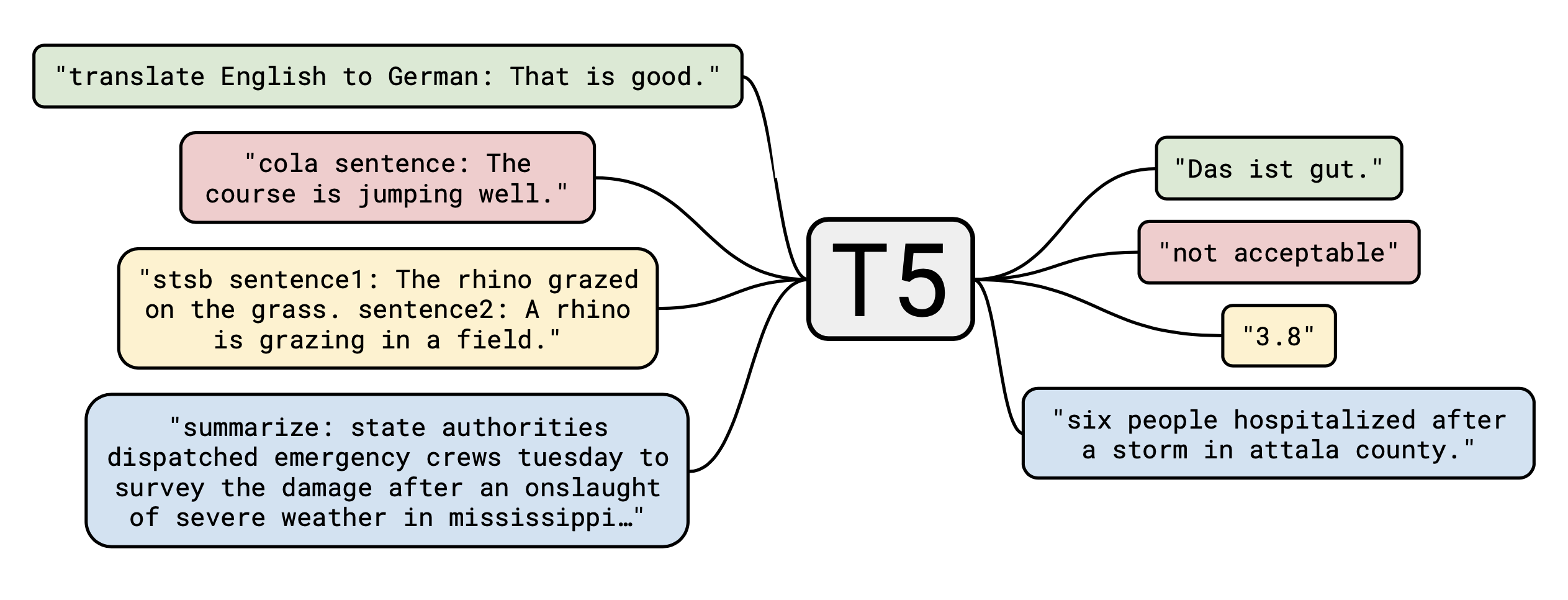

The language model T5 is short for “Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer” (Raffel et al., 2020). The encoder-decoder implementation follows the original Transformer architecture: tokens → embedding → encoder → decoder → output. T5 adopts the framework “Natural Language Decathlon” (McCann et al., 2018), where many common NLP tasks are translated into question-answering over a context. Instead of an explicit QA format, T5 uses short task prefixes to distinguish task intentions and separately fine-tunes the model on every individual task. The text-to-text framework enables easier transfer learning evaluation with the same model on a diverse set of tasks.

The model is trained on Web corpus extracted from Apr 2019 with various filters applied. The model is fine-tuned for each downstream task separately via “adapter layers” (add an extra layer for training) or “gradual unfreezing” (see ULMFiT). Both fine-tuning approaches only update partial parameters while keeping the majority of the model parameters unchanged. T5-11B achieved SOTA results on many NLP tasks.

As the authors mentioned in the paper “…our goal is not to propose new methods but instead to provide a comprehensive perspective on where the field stands”, the T5 long paper described a lot of training setup and evaluation processes in detail, a good read for people who are interested in training a LM from scratch.

GPT-3

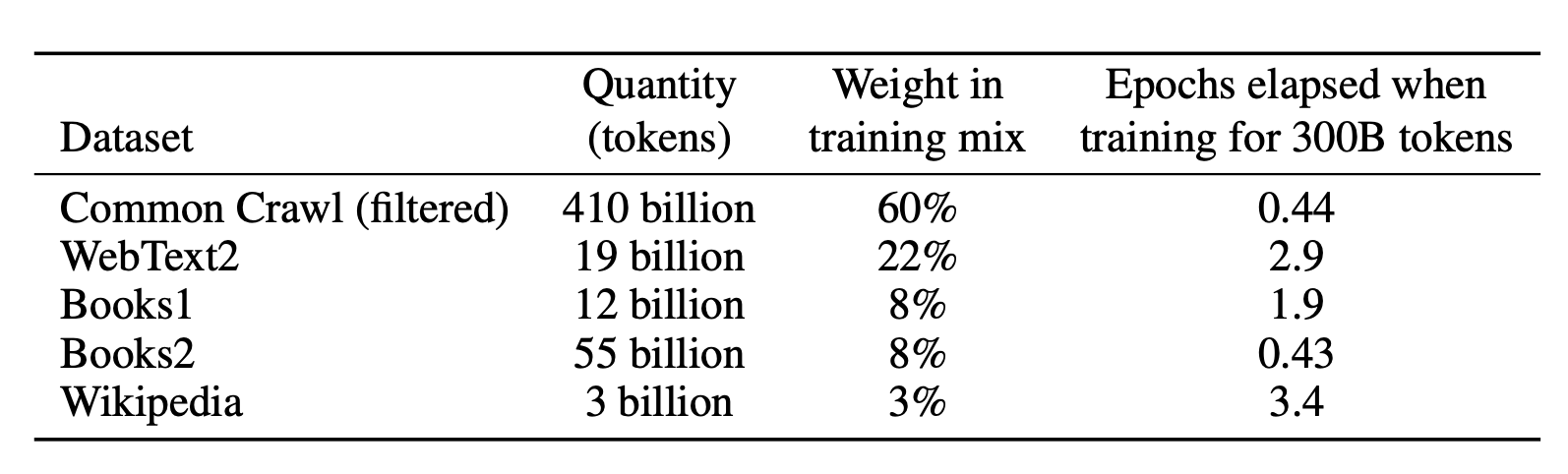

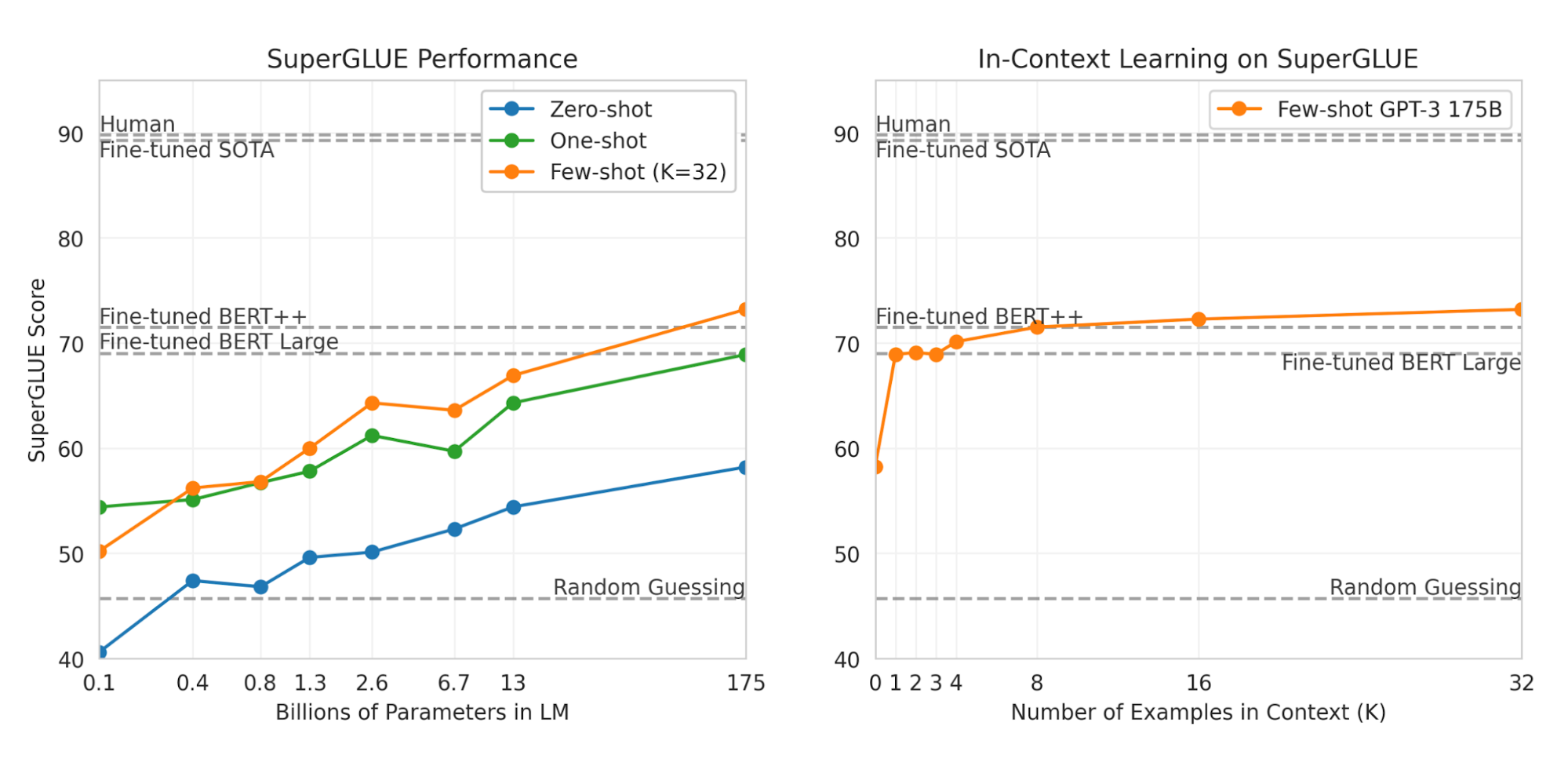

GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020) has the same architecture as GPT-2 but contains 175B parameters, 10x larger than GPT-2 (1.5B). In addition, GPT-3 uses alternating dense and locally banded sparse attention patterns, same as in sparse transformer. In order to fit such a huge model across multiple GPUs, GPT-3 is trained with partitions along both width and depth dimension. The training data is a filtered version of Common Crawl mixed with a few other high-quality curated datasets. To avoid the contamination that downstream tasks might appear in the training data, the authors attempted to remove all the overlaps with all the studied benchmark dataset from the training dataset. Unfortunately the filtering process is not perfect due to a bug.

For all the downstream evaluation, GPT-3 is tested in the few-shot setting without any gradient-based fine-tuning. Here the few-shot examples are provided as part of the prompt. GPT-3 achieves strong performance on many NLP datasets, comparable with fine-tuned BERT models.

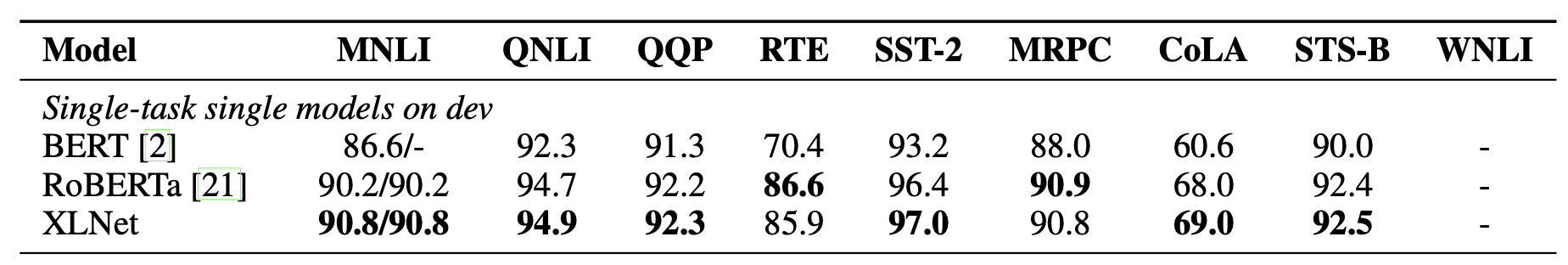

XLNet

The Autoregressive (AR) model such as GPT and autoencoder (AE) model such as BERT are two most common ways for language modeling. However, each has their own disadvantages: AR does not learn the bidirectional context, which is needed by downstream tasks like reading comprehension and AE assumes masked positions are independent given all other unmasked tokens which oversimplifies the long context dependency.

XLNet (Yang et al. 2019) generalizes the AE method to incorporate the benefits of AR. XLNet proposed the permutation language modeling objective. For a text sequence, it samples a factorization order $\mathbf{z}$ and decomposes the likelihood $p_\theta(\mathbf{x})$ according to this factorization order,

where $\mathcal{Z}_T$ is a set of all possible permutation of length $T$; $z_t$ and $\mathbf{z}_{<t}$ denote the $t$-th element and the first $t-1$ elements of a permutation $\mathbf{z} \in \mathcal{Z}_T$.

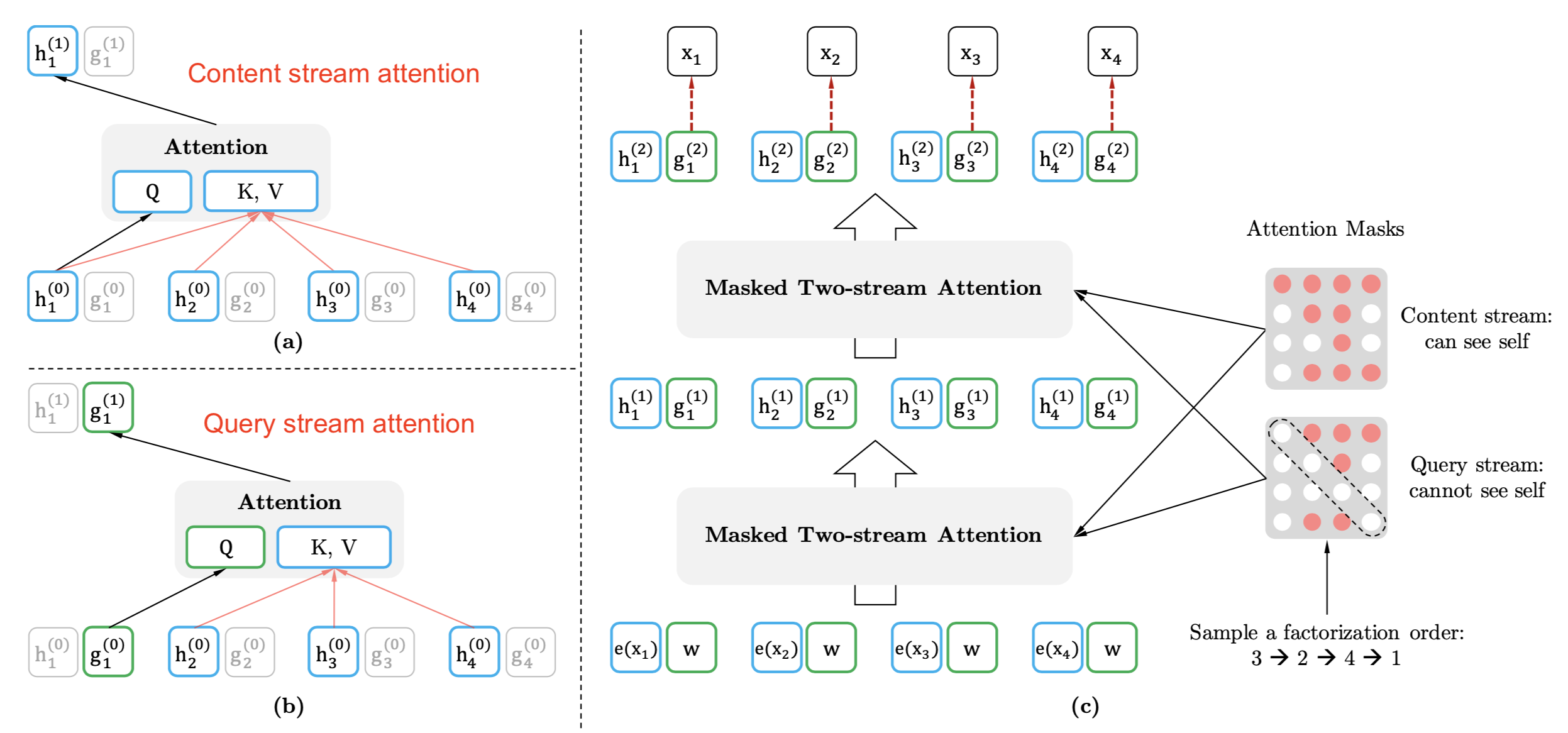

Note that the naive representation of the hidden state of the context, $h_\theta (\mathbf{x}_{\mathbf{z}_{<t}})$ in red, does not depend on which position the model tries to predict, as the permutation breaks the default ordering. Therefore, XLNet re-parameterized it to a function of the target position too, $g_\theta (\mathbf{x}_{\mathbf{z}_{<t}}, z_t)$ in blue.

However, two different requirements on $g_\theta (\mathbf{x}_{\mathbf{z}_{<t}}, z_t)$ lead to a two-stream self-attention design to accommodate:

- When predicting $x_{z_t}$, it should only encode the position $z_t$ but not the content $x_{z_t}$; otherwise it is trivial. This is wrapped into the “query representation” $g_{z_t} = g_\theta (\mathbf{x}_{\mathbf{z}_{<t}}, z_t)$ does not encode $x_{z_t}$.

- When predicting $x_j$ where $j > t$, it should encode the content $x_{z_t}$ as well to provide the full context. This is the “content representation” $h_{z_t} = h_\theta(\mathbf{x}_{\leq t})$.

Conceptually, the two streams of representations are updated as follows,

Given the difficulty of optimization in permutation language modeling, XLNet is set to only predict the last chunk of tokens in a factorization order.

The name in XLNet actually comes from Transformer-XL. It incorporates the design of Transformer-XL to extend the attention span by reusing hidden states from previous segments.

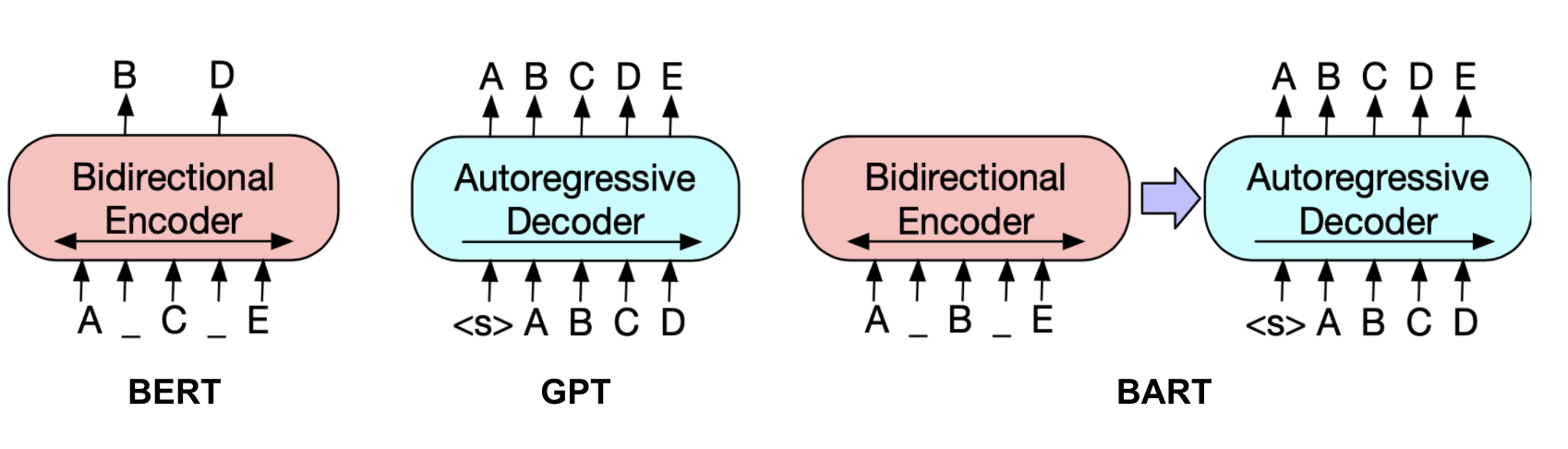

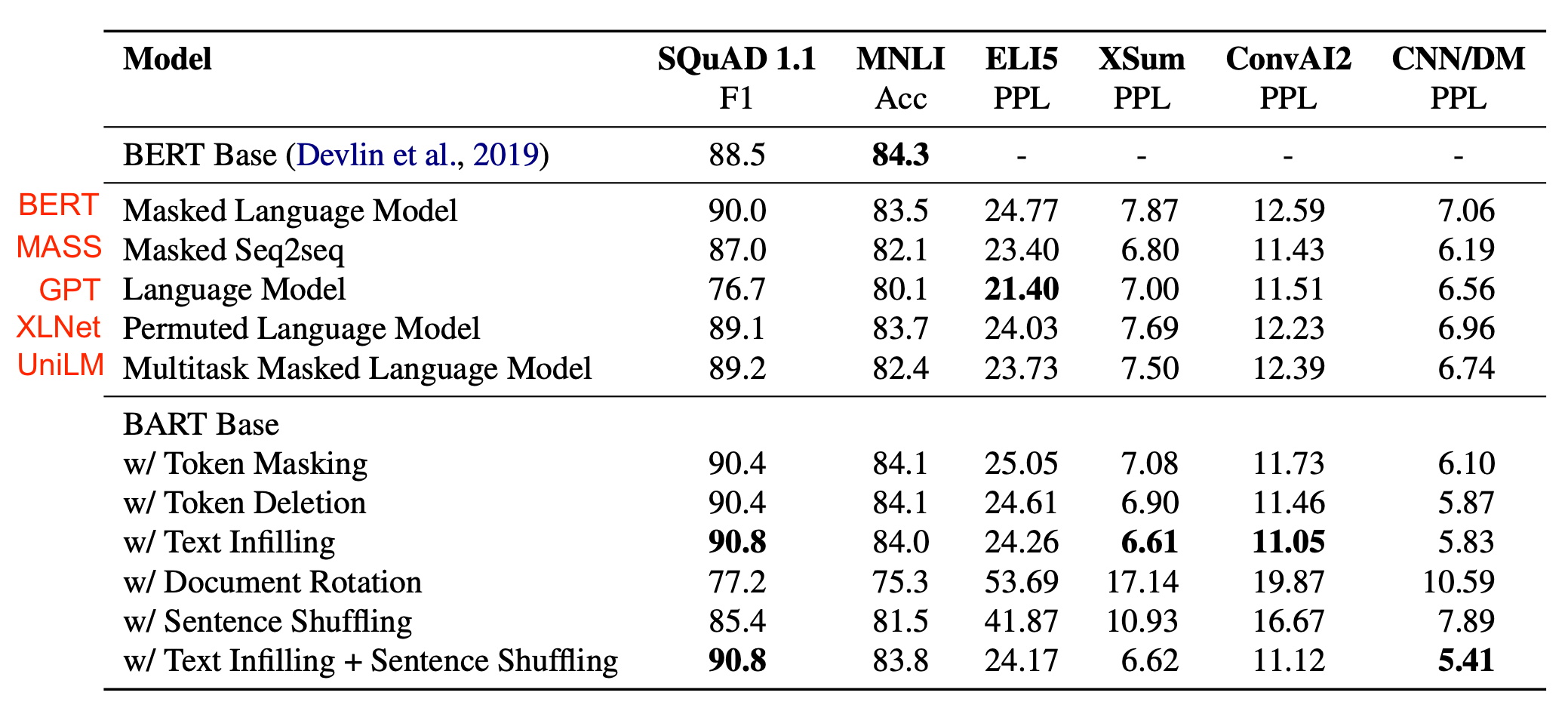

BART

BART (Lewis et al., 2019) is a denoising autoencoder to recover the original text from a randomly corrupted version. It combines Bidirectional and AutoRegressive Transformer: precisely, jointly training BERT-like bidirectional encoder and GPT-like autoregressive decoder together. The loss is simply just to minimize the negative log-likelihood.

They experimented with a variety of noising transformations, including token masking, token deletion, text infilling (i.e. A randomly sampled text span, which may contain multiple tokens, is replaced with a [MASK] token), sentence permutation, documentation rotation (i.e. A document is rotated to begin with a random token.). The best noising approach they discovered is text infilling and sentence shuffling.

Learnings from their experiments:

- The performance of pre-training methods varies significantly across downstream tasks.

- Token masking is crucial, as the performance is poor when only sentence permutation or documentation rotation is applied.

- Left-to-right pre-training improves generation.

- Bidirectional encoders are crucial for SQuAD.

- The pre-training objective is not the only important factor. Architectural improvements such as relative-position embeddings or segment-level recurrence matter too.

- Autoregressive language models perform best on ELI5.

- BART achieves the most consistently strong performance.

ELECTRA

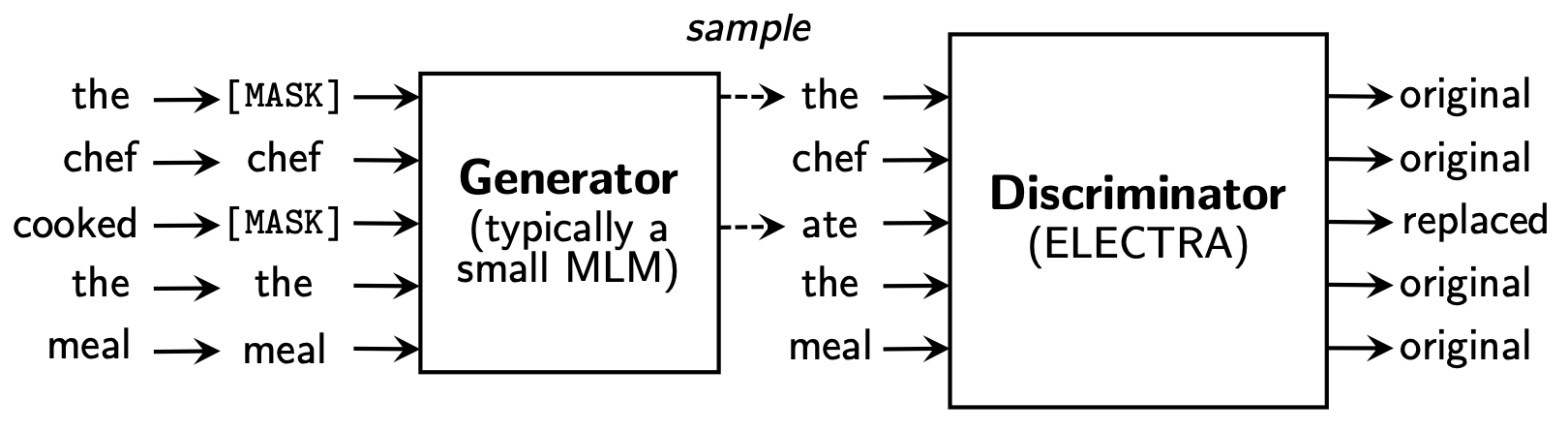

Most current pre-training large language models demand a lot of computation resources, raising concerns about their cost and accessibility. ELECTRA (“Efficiently Learning an Encoder that Classifies Token Replacements Accurately”; Clark et al. 2020) aims to improve the pre-training efficiency, which frames the language modeling as a discrimination task instead of generation task.

ELECTRA proposes a new pretraining task, called “Replaced Token Detection” (RTD). Let’s randomly sample $k$ positions to be masked. Each selected token in the original text is replaced by a plausible alternative predicted by a small language model, known as the generator $G$. The discriminator $D$ predicts whether each token is original or replaced.

The loss for the generator is the negative log-likelihood just as in other language models. The loss for the discriminator is the cross-entropy. Note that the generator is not adversarially trained to fool the discriminator but simply to optimize the NLL, since their experiments show negative results.

They found it more beneficial to only share the embeddings between generator & discriminator while using a small generator (1/4 to 1/2 the discriminator size), rather than sharing all the weights (i.e. two models have to be the same size then). In addition, joint training of the generator and discriminator works better than two-stage training of each alternatively.

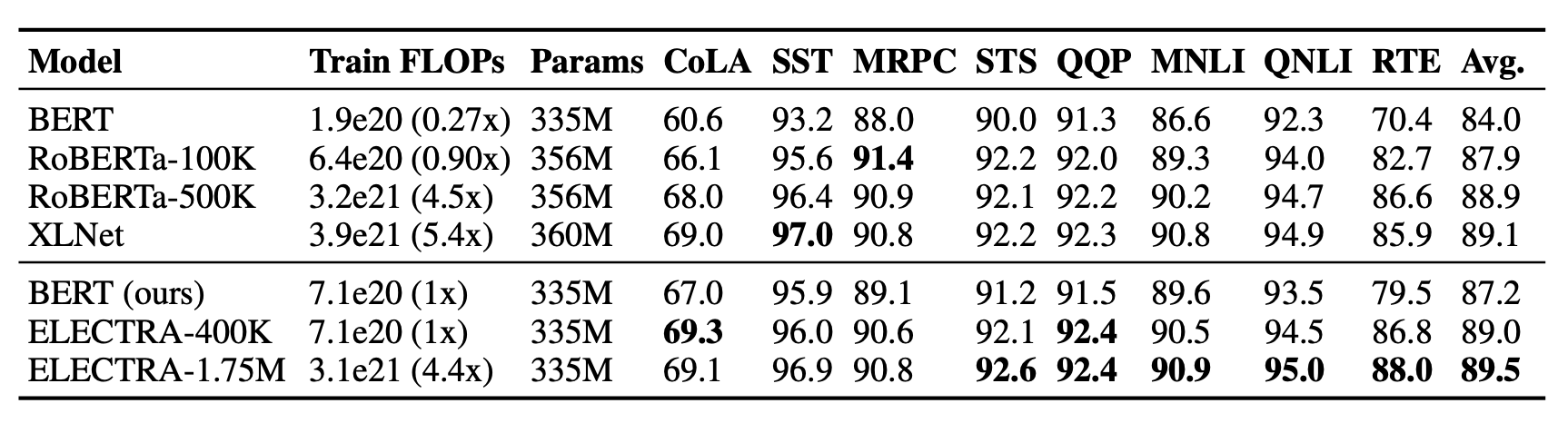

After pretraining the generator is discarded and only the ELECTRA discriminator is fine-tuned further for downstream tasks. The following table shows ELECTRA’s performance on the GLUE dev set.

Summary

| Base model | Pretraining Tasks | |

|---|---|---|

| CoVe | seq2seq NMT model | supervised learning using translation dataset. |

| ELMo | two-layer biLSTM | next token prediction |

| CVT | two-layer biLSTM | semi-supervised learning using both labeled and unlabeled datasets |

| ULMFiT | AWD-LSTM | autoregressive pretraining on Wikitext-103 |

| GPT | Transformer decoder | next token prediction |

| BERT | Transformer encoder | mask language model + next sentence prediction |

| ALBERT | same as BERT but light-weighted | mask language model + sentence order prediction |

| GPT-2 | Transformer decoder | next token prediction |

| RoBERTa | same as BERT | mask language model (dynamic masking) |

| T5 | Transformer encoder + decoder | pre-trained on a multi-task mixture of unsupervised and supervised tasks and for which each task is converted into a text-to-text format. |

| GPT-3 | Transformer decoder | next token prediction |

| XLNet | same as BERT | permutation language modeling |

| BART | BERT encoder + GPT decoder | reconstruct text from a noised version |

| ELECTRA | same as BERT | replace token detection |

Metric: Perplexity

Perplexity is often used as an intrinsic evaluation metric for gauging how well a language model can capture the real word distribution conditioned on the context.

A perplexity of a discrete proability distribution $p$ is defined as the exponentiation of the entropy:

Given a sentence with $N$ words, $s = (w_1, \dots, w_N)$, the entropy looks as follows, simply assuming that each word has the same frequency, $\frac{1}{N}$:

The perplexity for the sentence becomes:

A good language model should predict high word probabilities. Therefore, the smaller perplexity the better.

Common Tasks and Datasets

- SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset): A reading comprehension dataset, consisting of questions posed on a set of Wikipedia articles, where the answer to every question is a span of text.

- RACE (ReAding Comprehension from Examinations): A large-scale reading comprehension dataset with more than 28,000 passages and nearly 100,000 questions. The dataset is collected from English examinations in China, which are designed for middle school and high school students.

- See more QA datasets in a later post.

Commonsense Reasoning

- Story Cloze Test: A commonsense reasoning framework for evaluating story understanding and generation. The test requires a system to choose the correct ending to multi-sentence stories from two options.

- SWAG (Situations With Adversarial Generations): multiple choices; contains 113k sentence-pair completion examples that evaluate grounded common-sense inference

Natural Language Inference (NLI): also known as Text Entailment, an exercise to discern in logic whether one sentence can be inferred from another.

- RTE (Recognizing Textual Entailment): A set of datasets initiated by text entailment challenges.

- SNLI (Stanford Natural Language Inference): A collection of 570k human-written English sentence pairs manually labeled for balanced classification with the labels

entailment,contradiction, andneutral. - MNLI (Multi-Genre NLI): Similar to SNLI, but with a more diverse variety of text styles and topics, collected from transcribed speech, popular fiction, and government reports.

- QNLI (Question NLI): Converted from SQuAD dataset to be a binary classification task over pairs of (question, sentence).

- SciTail: An entailment dataset created from multiple-choice science exams and web sentences.

Named Entity Recognition (NER): labels sequences of words in a text which are the names of things, such as person and company names, or gene and protein names

- CoNLL 2003 NER task: consists of newswire from the Reuters, concentrating on four types of named entities: persons, locations, organizations and names of miscellaneous entities.

- OntoNotes 5.0: This corpus contains text in English, Arabic and Chinese, tagged with four different entity types (PER, LOC, ORG, MISC).

- Reuters Corpus: A large collection of Reuters News stories.

- Fine-Grained NER (FGN)

Sentiment Analysis

- SST (Stanford Sentiment Treebank)

- IMDb: A large dataset of movie reviews with binary sentiment classification labels.

Semantic Role Labeling (SRL): models the predicate-argument structure of a sentence, and is often described as answering “Who did what to whom”.

Sentence similarity: also known as paraphrase detection

- MRPC (MicRosoft Paraphrase Corpus): It contains pairs of sentences extracted from news sources on the web, with annotations indicating whether each pair is semantically equivalent.

- QQP (Quora Question Pairs) STS Benchmark: Semantic Textual Similarity

Sentence Acceptability: a task to annotate sentences for grammatical acceptability.

- CoLA (Corpus of Linguistic Acceptability): a binary single-sentence classification task.

Text Chunking: To divide a text in syntactically correlated parts of words.

Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging: tag parts of speech to each token, such as noun, verb, adjective, etc. the Wall Street Journal portion of the Penn Treebank (Marcus et al., 1993).

Machine Translation: See Standard NLP page.

- WMT 2015 English-Czech data (Large)

- WMT 2014 English-German data (Medium)

- IWSLT 2015 English-Vietnamese data (Small)

Coreference Resolution: cluster mentions in text that refer to the same underlying real world entities.

Long-range Dependency

- LAMBADA (LAnguage Modeling Broadened to Account for Discourse Aspects): A collection of narrative passages extracted from the BookCorpus and the task is to predict the last word, which require at least 50 tokens of context for a human to successfully predict.

- Children’s Book Test: is built from books that are freely available in Project Gutenberg. The task is to predict the missing word among 10 candidates.

Multi-task benchmark

- GLUE multi-task benchmark: https://gluebenchmark.com

- decaNLP benmark: https://decanlp.com

Unsupervised pretraining dataset

- Books corpus: The corpus contains “over 7,000 unique unpublished books from a variety of genres including Adventure, Fantasy, and Romance.”

- 1B Word Language Model Benchmark

- English Wikipedia: ~2500M words

Cited as:

@article{weng2019LM,

title = "Generalized Language Models",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2019",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2019-01-31-lm/"

}

Reference

[1] Bryan McCann, et al. “Learned in translation: Contextualized word vectors.” NIPS. 2017.

[2] Kevin Clark et al. “Semi-Supervised Sequence Modeling with Cross-View Training.” EMNLP 2018.

[3] Matthew E. Peters, et al. “Deep contextualized word representations.” NAACL-HLT 2017.

[4] OpenAI Blog “Improving Language Understanding with Unsupervised Learning”, June 11, 2018.

[5] OpenAI Blog “Better Language Models and Their Implications.” Feb 14, 2019.

[6] Jeremy Howard and Sebastian Ruder. “Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification.” ACL 2018.

[7] Alec Radford et al. “Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training”. OpenAI Blog, June 11, 2018.

[8] Jacob Devlin, et al. “BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding.” arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

[9] Mike Schuster, and Kaisuke Nakajima. “Japanese and Korean voice search.” ICASSP. 2012.

[10] Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap between Human and Machine Translation

[11] Ashish Vaswani, et al. “Attention is all you need.” NIPS 2017.

[12] Peter J. Liu, et al. “Generating wikipedia by summarizing long sequences.” ICLR 2018.

[13] Sebastian Ruder. “10 Exciting Ideas of 2018 in NLP” Dec 2018.

[14] Alec Radford, et al. “Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners.”. 2019.

[15] Rico Sennrich, et al. “Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.07909. 2015.

[16] Zhenzhong Lan, et al. “ALBERT: A Lite BERT for Self-supervised Learning of Language Representations.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1909.11942 (2019).

[17] Yinhan Liu, et al. “RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1907.11692 (2019).

[18] Tom B Brown, et al. “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners” NeuriPS 2020.

[19] Zhilin Yang et al. “XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding.” NeuriPS 2019.

[20] Mike Lewis et al. “BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension.” ACL 2020.

[21] Kevin Clark et al. “ELECTRA: Pre-training Text Encoders as Discriminators Rather Than Generators.” ICLR 2020.

[22] Colin Raffel, et al. “Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer” JMLR 2020.