[Updated on 2019-05-27: add the section on Lottery Ticket Hypothesis.]

If you are like me, entering into the field of deep learning with experience in traditional machine learning, you may often ponder over this question: Since a typical deep neural network has so many parameters and training error can easily be perfect, it should surely suffer from substantial overfitting. How could it be ever generalized to out-of-sample data points?

The effort in understanding why deep neural networks can generalize somehow reminds me of this interesting paper on System Biology — “Can a biologist fix a radio?” (Lazebnik, 2002). If a biologist intends to fix a radio machine like how she works on a biological system, life could be hard. Because the full mechanism of the radio system is not revealed, poking small local functionalities might give some hints but it can hardly present all the interactions within the system, let alone the entire working flow. No matter whether you think it is relevant to DL, it is a very fun read.

I would like to discuss a couple of papers on generalizability and complexity measurement of deep learning models in the post. Hopefully, it could shed light on your thinking path towards the understanding of why DNN can generalize.

Classic Theorems on Compression and Model Selection

Let’s say we have a classification problem and a dataset, we can develop many models to solve it, from fitting a simple linear regression to memorizing the full dataset in disk space. Which one is better? If we only care about the accuracy over training data (especially given that testing data is likely unknown), the memorization approach seems to be the best — well, it doesn’t sound right.

There are many classic theorems to guide us when deciding what types of properties a good model should possess in such scenarios.

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s Razor is an informal principle for problem-solving, proposed by William of Ockham in the 14th century:

“Simpler solutions are more likely to be correct than complex ones.”

The statement is extremely powerful when we are facing multiple candidates of underlying theories to explain the world and have to pick one. Too many unnecessary assumptions might seem to be plausible for one problem, but harder to be generalized to other complications or to eventually lead to the basic principles of the universe.

Think of this, it took people hundreds of years to figure out that the sky is blue in the daytime but reddish at sunset are because of the same reason (Rayleigh scattering), although two phenomena look very different. People must have proposed many other explanations for them separately but the unified and simple version won eventually.

Minimum Description Length principle

The principle of Occam’s Razor can be similarly applied to machine learning models. A formalized version of such concept is called the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle, used for comparing competing models / explanations given data observed.

“Comprehension is compression.”

The fundamental idea in MDL is to view learning as data compression. By compressing the data, we need to discover regularity or patterns in the data with the high potentiality to generalize to unseen samples. Information bottleneck theory believes that a deep neural network is trained first to represent the data by minimizing the generalization error and then learn to compress this representation by trimming noise.

Meanwhile, MDL considers the model description as part of the compression delivery, so the model cannot be arbitrarily large.

A two-part version of MDL principle states that: Let $\mathcal{H}^{(1)}, \mathcal{H}^{(2)}, \dots$ be a list of models that can explain the dataset $\mathcal{D}$. The best hypothesis among them should be the one that minimizes the sum:

- $L(\mathcal{H})$ is the length of the description of model $\mathcal{H}$ in bits.

- $L(\mathcal{D}\vert\mathcal{H})$ is the length of the description of the data $\mathcal{D}$ in bits when encoded with $\mathcal{H}$.

In simple words, the best model is the smallest model containing the encoded data and the model itself. Following this criterion, the memorization approach I proposed at the beginning of the section sounds horrible no matter how good accuracy it can achieve on the training data.

People might argue Occam’s Razor is wrong, as given the real world can be arbitrarily complicated, why do we have to find simple models? One interesting view by MDL is to consider models as “languages” instead of fundamental generative theorems. We would like to find good compression strategies to describe regularity in a small set of samples, and they do not have to be the “real” generative model for explaining the phenomenon. Models can be wrong but still useful (i.e., think of any Bayesian prior).

Kolmogorov Complexity

Kolmogorov Complexity relies on the concept of modern computers to define the algorithmic (descriptive) complexity of an object: It is the length of the shortest binary computer program that describes the object. Following MDL, a computer is essentially the most general form of data decompressor.

The formal definition of Kolmogorov Complexity states that: Given a universal computer $\mathcal{U}$ and a program $p$, let’s denote $\mathcal{U}(p)$ as the output of the computer processing the program and $L(p)$ as the descriptive length of the program. Then Kolmogorov Complexity $K_\mathcal{U}$ of a string $s$ with respect to a universal computer $\mathcal{U}$ is:

Note that a universal computer is one that can mimic the actions of any other computers. All modern computers are universal as they can all be reduced to Turing machines. The definition is universal no matter which computers we are using, because another universal computer can always be programmed to clone the behavior of $\mathcal{U}$, while encoding this clone program is just a constant.

There are a lot of connections between Kolmogorov Complexity and Shannon Information Theory, as both are tied to universal coding. It is an amazing fact that the expected Kolmogorov Complexity of a random variable is approximately equal to its Shannon entropy (see Sec 2.3 of the report). More on this topic is out of the scope here, but there are many interesting readings online. Help yourself :)

Solomonoff’s Inference Theory

Another mathematical formalization of Occam’s Razor is Solomonoff’s theory of universal inductive inference (Solomonoff, 1964). The principle is to favor models that correspond to the “shortest program” to produce the training data, based on its Kolmogorov complexity

Expressive Power of DL Models

Deep neural networks have an extremely large number of parameters compared to the traditional statistical models. If we use MDL to measure the complexity of a deep neural network and consider the number of parameters as the model description length, it would look awful. The model description $L(\mathcal{H})$ can easily grow out of control.

However, having numerous parameters is necessary for a neural network to obtain high expressivity power. Because of its great capability to capture any flexible data representation, deep neural networks have achieved great success in many applications.

Universal Approximation Theorem

The Universal Approximation Theorem states that a feedforward network with: 1) a linear output layer, 2) at least one hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons and 3) some activation function can approximate any continuous functions on a compact subset of $\mathbb{R}^n$ to arbitrary accuracy. The theorem was first proved for sigmoid activation function (Cybenko, 1989). Later it was shown that the universal approximation property is not specific to the choice of activation (Hornik, 1991) but the multilayer feedforward architecture.

Although a feedforward network with a single layer is sufficient to represent any function, the width has to be exponentially large. The universal approximation theorem does not guarantee whether the model can be learned or generalized properly. Often, adding more layers helps to reduce the number of hidden neurons needed in a shallow network.

To take advantage of the universal approximation theorem, we can always find a neural network to represent the target function with error under any desired threshold, but we need to pay the price — the network might grow super large.

Proof: Finite Sample Expressivity of Two-layer NN

The Universal Approximation Theorem we have discussed so far does not consider a finite sample set. Zhang, et al. (2017) provided a neat proof on the finite-sample expressivity of two-layer neural networks.

A neural network $C$ can represent any function given a sample size $n$ in $d$ dimensions if: For every finite sample set $S \subseteq \mathbb{R}^d$ with $\vert S \vert = n$ and every function defined on this sample set: $f: S \mapsto \mathbb{R}$, we can find a set of weight configuration for $C$ so that $C(\boldsymbol{x}) = f(\boldsymbol{x}), \forall \boldsymbol{x} \in S$.

The paper proposed a theorem:

There exists a two-layer neural network with ReLU activations and $2n + d$ weights that can represent any function on a sample of size $n$ in $d$ dimensions.

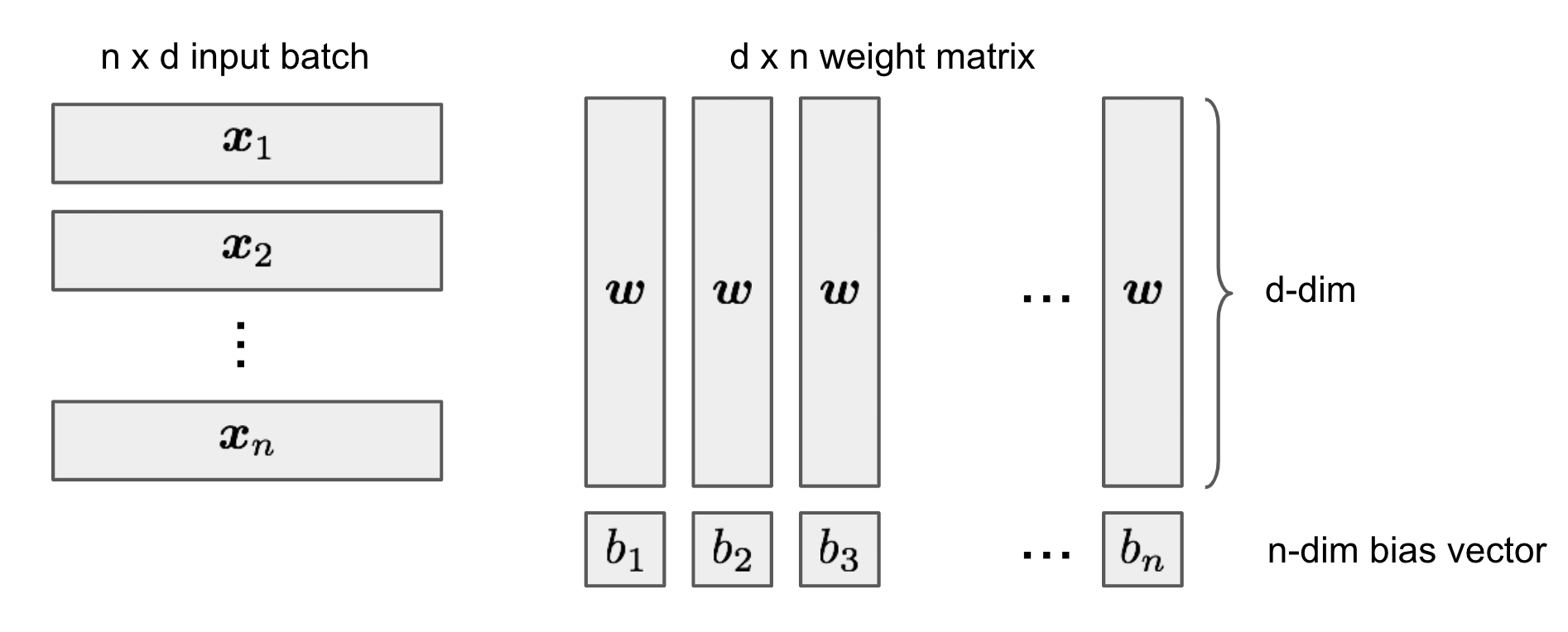

Proof. First we would like to construct a two-layer neural network $C: \mathbb{R}^d \mapsto \mathbb{R}$. The input is a $d$-dimensional vector, $\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d$. The hidden layer has $h$ hidden units, associated with a weight matrix $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times h}$, a bias vector $-\mathbf{b} \in \mathbb{R}^h$ and ReLU activation function. The second layer outputs a scalar value with weight vector $\boldsymbol{v} \in \mathbb{R}^h$ and zero biases.

The output of network $C$ for a input vector $\boldsymbol{x}$ can be represented as follows:

where $\boldsymbol{W}_{(:,i)}$ is the $i$-th column in the $d \times h$ matrix.

Given a sample set $S = \{\boldsymbol{x}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n\}$ and target values $\boldsymbol{y} = \{y_1, \dots, y_n \}$, we would like to find proper weights $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times h}$, $\boldsymbol{b}, \boldsymbol{v} \in \mathbb{R}^h$ so that $C(\boldsymbol{x}_i) = y_i, \forall i=1,\dots,n$.

Let’s combine all sample points into one batch as one input matrix $\mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}$. If set $h=n$, $\mathbf{X}\mathbf{W} - \boldsymbol{b}$ would be a square matrix of size $n \times n$.

We can simplify $\mathbf{W}$ to have the same column vectors across all the columns:

Let $a_i = \boldsymbol{x}_i \boldsymbol{w}$, we would like to find a suitable $\boldsymbol{w}$ and $\boldsymbol{b}$ such that $b_1 < a_1 < b_2 < a_2 < \dots < b_n < a_n$. This is always achievable because we try to solve $n+d$ unknown variables with $n$ constraints and $\boldsymbol{x}_i$ are independent (i.e. pick a random $\boldsymbol{w}$, sort $\boldsymbol{x}_i \boldsymbol{w}$ and then set $b_j$’s as values in between). Then $\mathbf{M}_\text{ReLU}$ becomes a lower triangular matrix:

It is a nonsingular square matrix as $\det(\mathbf{M}_\text{ReLU}) \neq 0$, so we can always find suitable $\boldsymbol{v}$ to solve $\boldsymbol{v}\mathbf{M}_\text{ReLU}=\boldsymbol{y}$ (In other words, the column space of $\mathbf{M}_\text{ReLU}$ is all of $\mathbb{R}^n$ and we can find a linear combination of column vectors to obtain any $\boldsymbol{y}$).

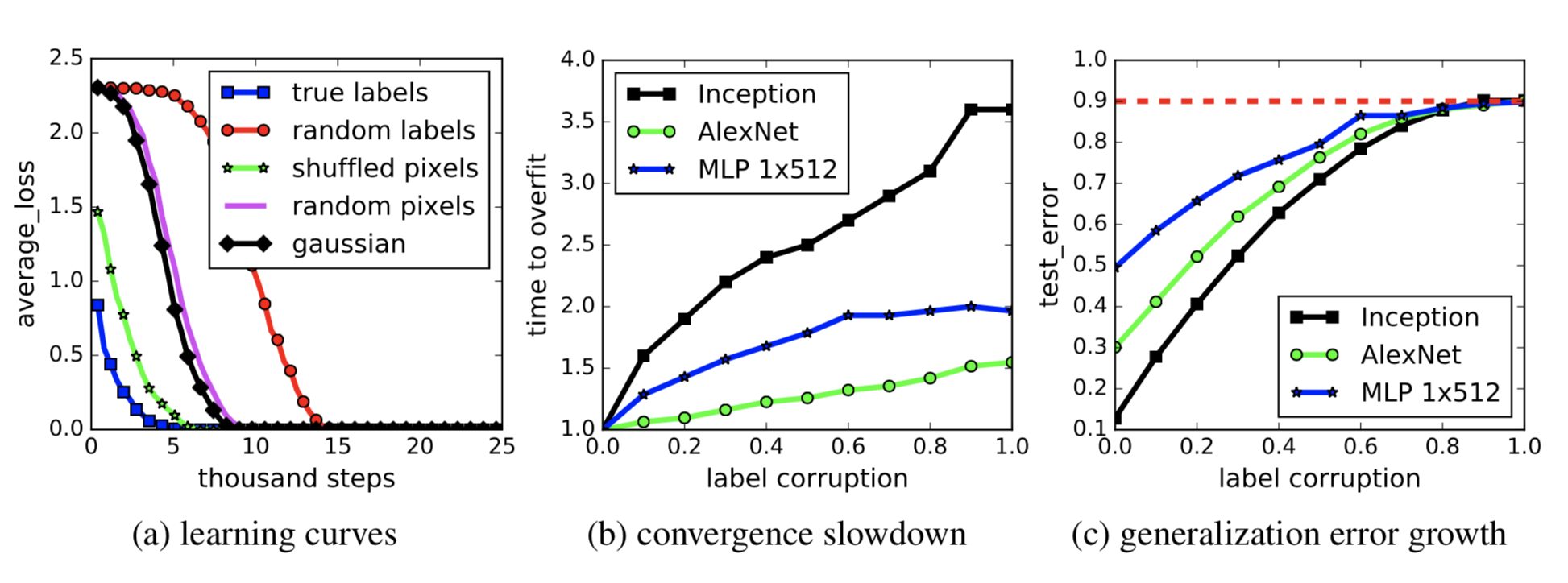

Deep NN can Learn Random Noise

As we know two-layer neural networks are universal approximators, it is less surprising to see that they are able to learn unstructured random noise perfectly, as shown in Zhang, et al. (2017). If labels of image classification dataset are randomly shuffled, the high expressivity power of deep neural networks can still empower them to achieve near-zero training loss. These results do not change with regularization terms added.

Are Deep Learning Models Dramatically Overfitted?

Deep learning models are heavily over-parameterized and can often get to perfect results on training data. In the traditional view, like bias-variance trade-offs, this could be a disaster that nothing may generalize to the unseen test data. However, as is often the case, such “overfitted” (training error = 0) deep learning models still present a decent performance on out-of-sample test data. Hmm … interesting and why?

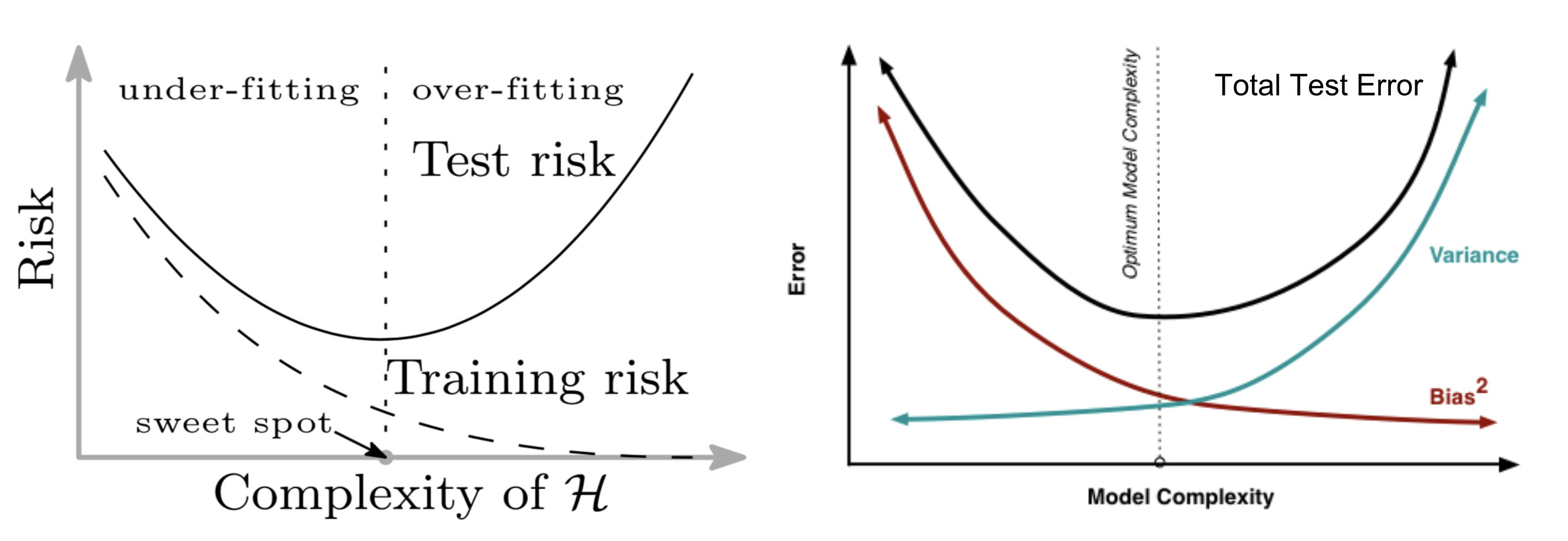

Modern Risk Curve for Deep Learning

The traditional machine learning uses the following U-shape risk curve to measure the bias-variance trade-offs and quantify how generalizable a model is. If I get asked how to tell whether a model is overfitted, this would be the first thing popping into my mind.

As the model turns larger (more parameters added), the training error decreases to close to zero, but the test error (generalization error) starts to increase once the model complexity grows to pass the threshold between “underfitting” and “overfitting”. In a way, this is well aligned with Occam’s Razor.

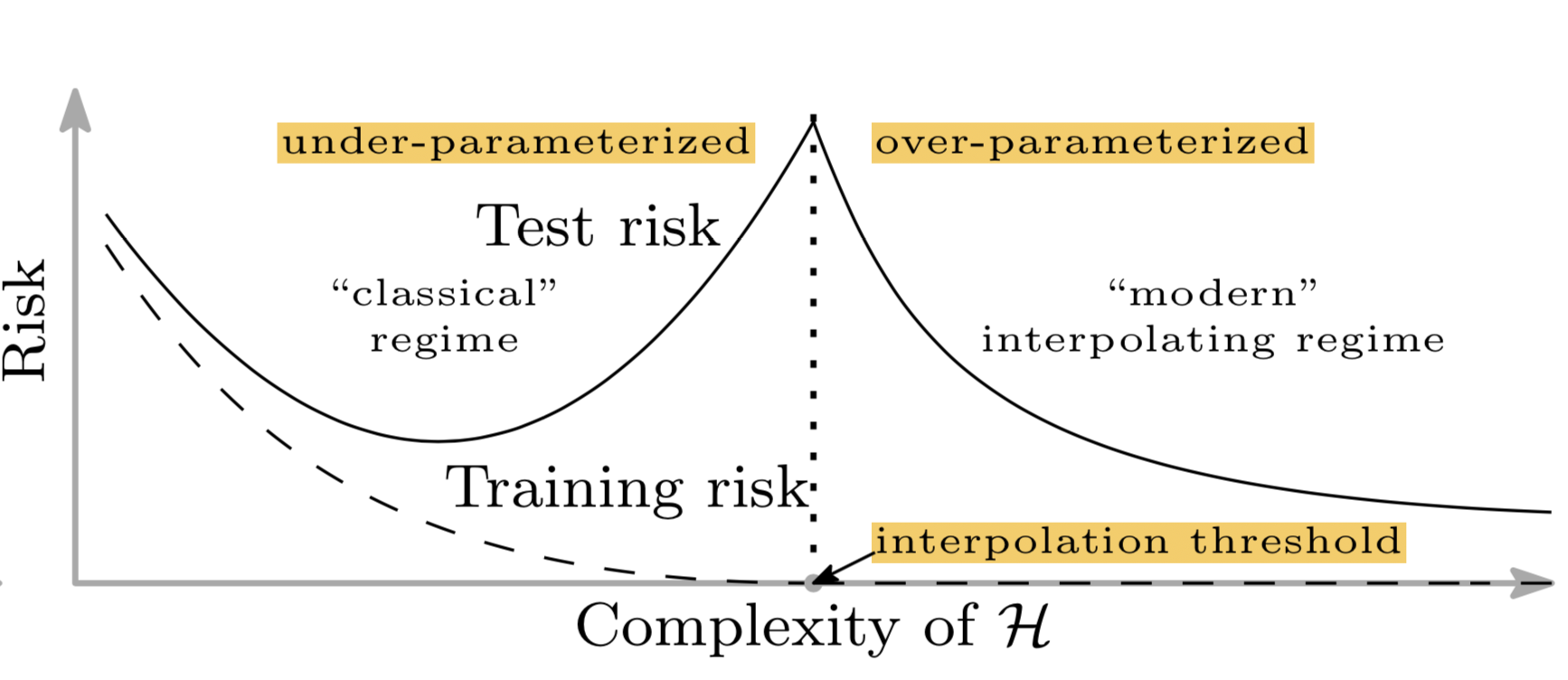

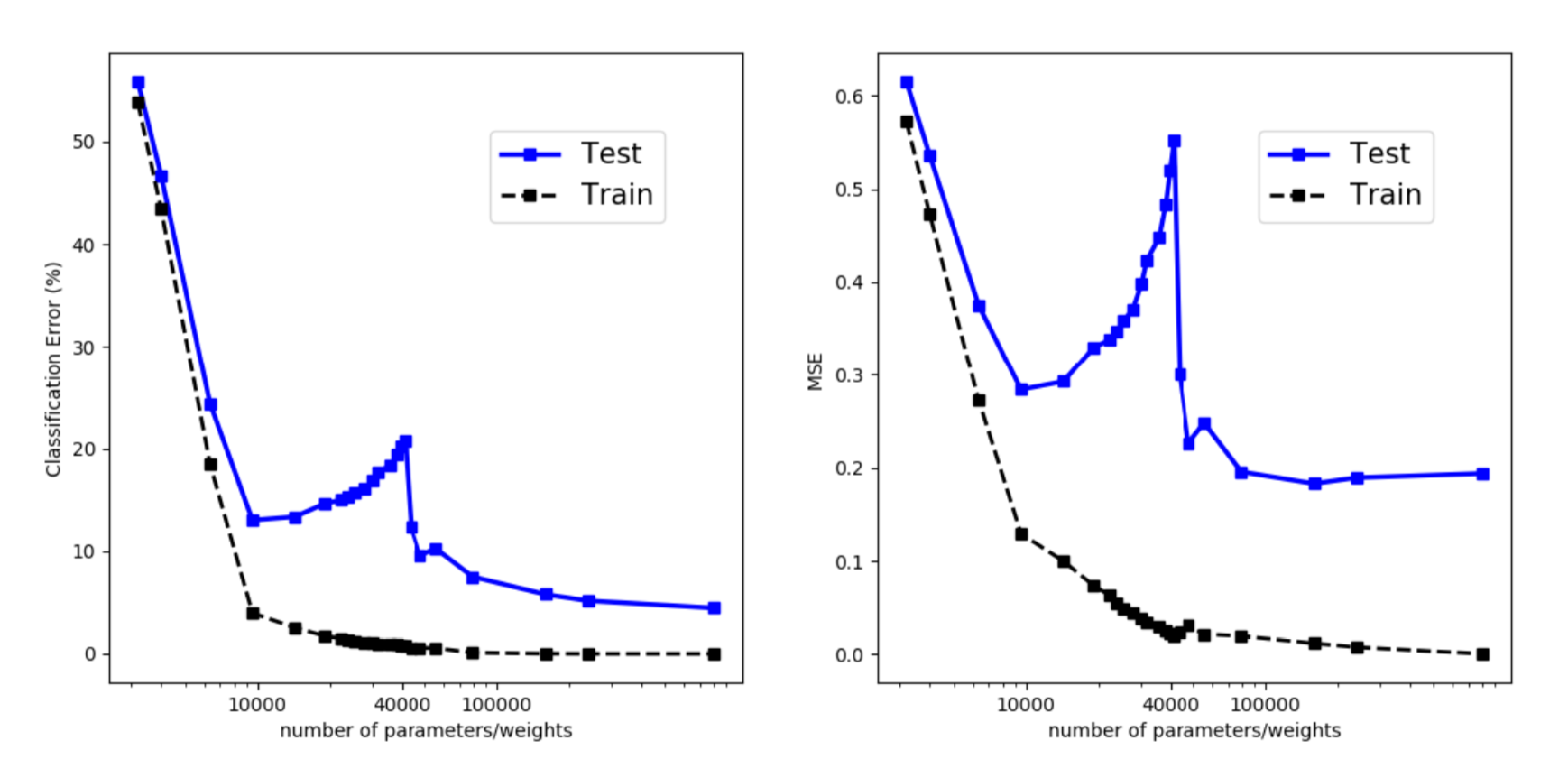

Unfortunately this does not apply to deep learning models. Belkin et al. (2018) reconciled the traditional bias-variance trade-offs and proposed a new double-U-shaped risk curve for deep neural networks. Once the number of network parameters is high enough, the risk curve enters another regime.

The paper claimed that it is likely due to two reasons:

- The number of parameters is not a good measure of inductive bias, defined as the set of assumptions of a learning algorithm used to predict for unknown samples. See more discussion on DL model complexity in later sections.

- Equipped with a larger model, we might be able to discover larger function classes and further find interpolating functions that have smaller norm and are thus “simpler”.

The double-U-shaped risk curve was observed empirically, as shown in the paper. However I was struggling quite a bit to reproduce the results. There are some signs of life, but in order to generate a pretty smooth curve similar to the theorem, many details in the experiment have to be taken care of.

Regularization is not the Key to Generalization

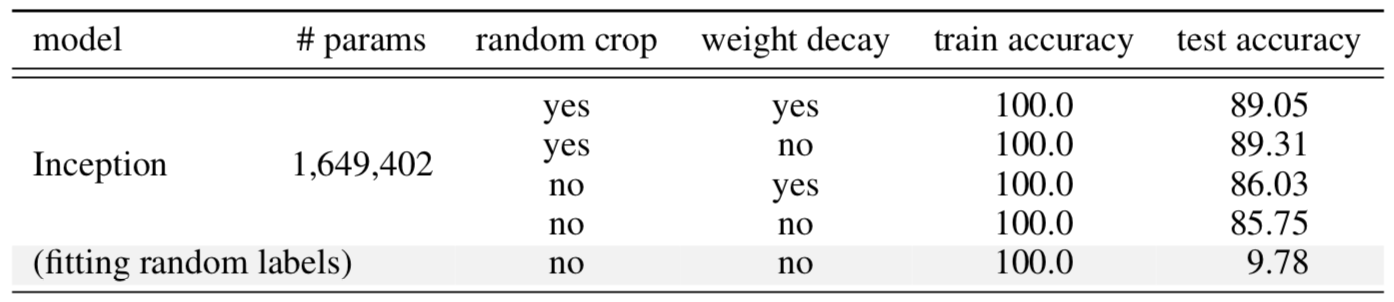

Regularization is a common way to control overfitting and improve model generalization performance. Interestingly some research (Zhang, et al. 2017) has shown that explicit regularization (i.e. data augmentation, weight decay and dropout) is neither necessary or sufficient for reducing generalization error.

Taking the Inception model trained on CIFAR10 as an example (see Fig. 5), regularization techniques help with out-of-sample generalization but not much. No single regularization seems to be critical independent of other terms. Thus, it is unlikely that regularizers are the fundamental reason for generalization.

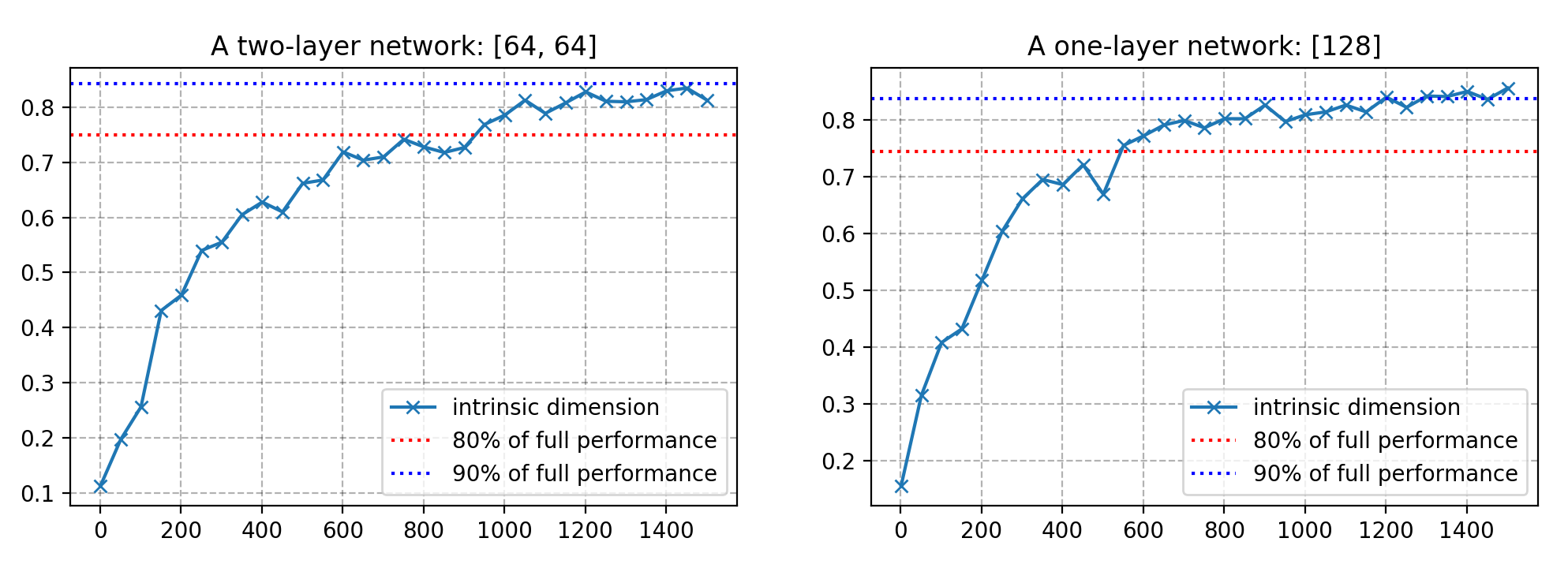

Intrinsic Dimension

The number of parameters is not correlated with model overfitting in the field of deep learning, suggesting that parameter counting cannot indicate the true complexity of deep neural networks.

Apart from parameter counting, researchers have proposed many ways to quantify the complexity of these models, such as the number of degrees of freedom of models (Gao & Jojic, 2016), or prequential code (Blier & Ollivier, 2018).

I would like to discuss a recent method on this matter, named intrinsic dimension (Li et al, 2018). Intrinsic dimension is intuitive, easy to measure, while still revealing many interesting properties of models of different sizes.

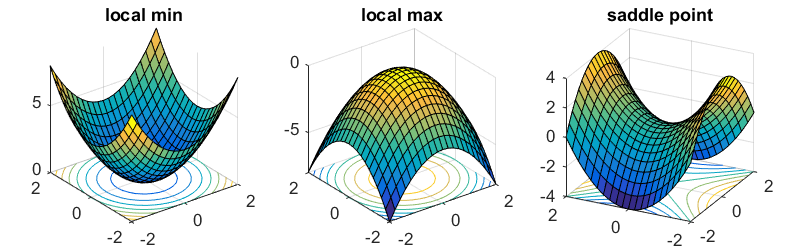

Considering a neural network with a great number of parameters, forming a high-dimensional parameter space, the learning happens on this high-dimensional objective landscape. The shape of the parameter space manifold is critical. For example, a smoother manifold is beneficial for optimization by providing more predictive gradients and allowing for larger learning rates—this was claimed to be the reason why batch normalization has succeeded in stabilizing training (Santurkar, et al, 2019).

Even though the parameter space is huge, fortunately we don’t have to worry too much about the optimization process getting stuck in local optima, as it has been shown that local optimal points in the objective landscape almost always lay in saddle-points rather than valleys. In other words, there is always a subset of dimensions containing paths to leave local optima and keep on exploring.

One intuition behind the measurement of intrinsic dimension is that, since the parameter space has such high dimensionality, it is probably not necessary to exploit all the dimensions to learn efficiently. If we only travel through a slice of objective landscape and still can learn a good solution, the complexity of the resulting model is likely lower than what it appears to be by parameter-counting. This is essentially what intrinsic dimension tries to assess.

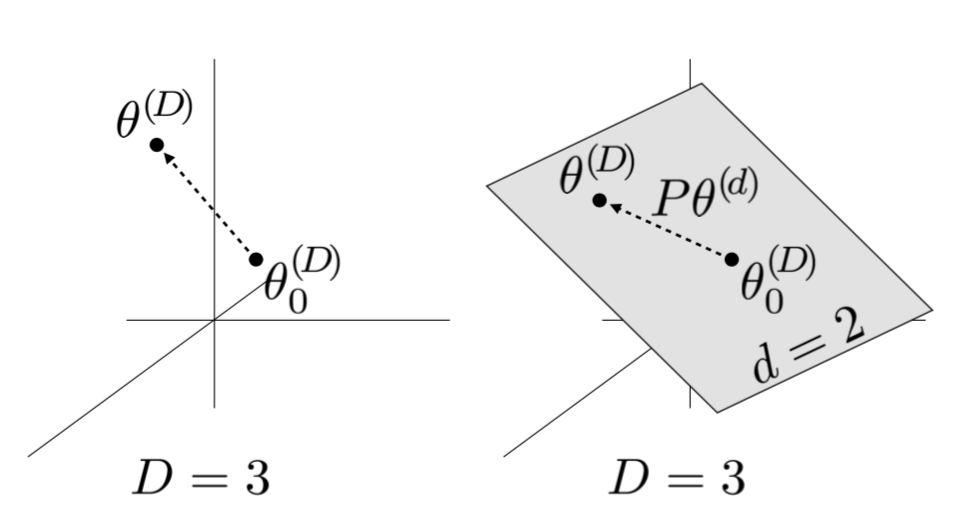

Say a model has $D$ dimensions and its parameters are denoted as $\theta^{(D)}$. For learning, a smaller $d$-dimensional subspace is randomly sampled, $\theta^{(d)}$, where $d < D$. During one optimization update, rather than taking a gradient step according to all $D$ dimensions, only the smaller subspace $\theta^{(d)}$ is used and remapped to update model parameters.

The gradient update formula looks like the follows:

where $\theta_0^{(D)}$ are the initialization values and $\mathbf{P}$ is a $D \times d$ projection matrix that is randomly sampled before training. Both $\theta_0^{(D)}$ and $\mathbf{P}$ are not trainable and fixed during training. $\theta^{(d)}$ is initialized as all zeros.

By searching through the value of $d = 1, 2, \dots, D$, the corresponding $d$ when the solution emerges is defined as the intrinsic dimension.

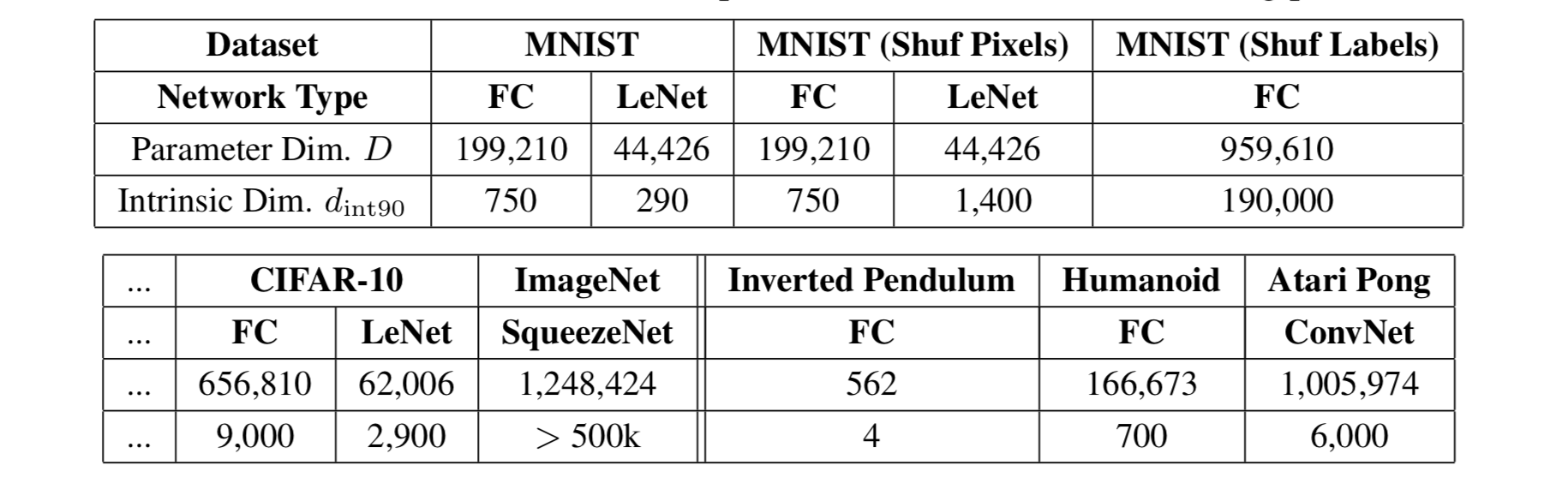

It turns out many problems have much smaller intrinsic dimensions than the number of parameters. For example, on CIFAR10 image classification, a fully-connected network with 650k+ parameters has only 9k intrinsic dimension and a convolutional network containing 62k parameters has an even lower intrinsic dimension of 2.9k.

The measurement of intrinsic dimensions suggests that deep learning models are significantly simpler than what they might appear to be.

Heterogeneous Layer Robustness

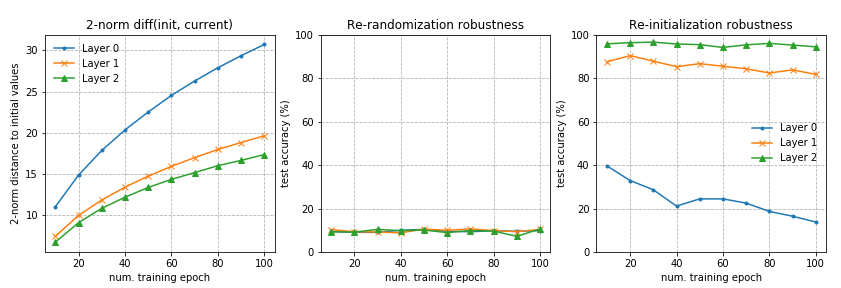

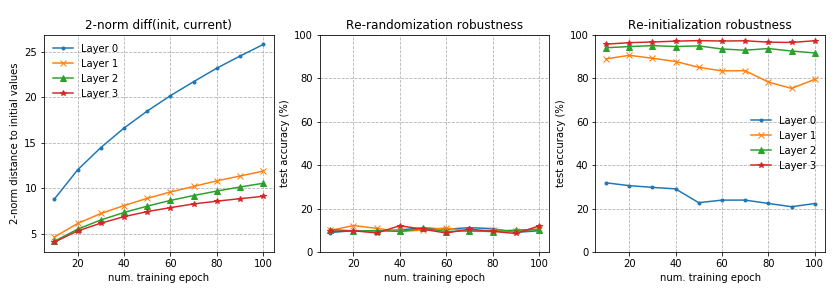

Zhang et al. (2019) investigated the role of parameters in different layers. The fundamental question raised by the paper is: “are all layers created equal?” The short answer is: No. The model is more sensitive to changes in some layers but not others.

The paper proposed two types of operations that can be applied to parameters of the $\ell$-th layer, $\ell = 1, \dots, L$, at time $t$, $\theta^{(\ell)}_t$ to test their impacts on model robustness:

-

Re-initialization: Reset the parameters to the initial values, $\theta^{(\ell)}_t \leftarrow \theta^{(\ell)}_0$. The performance of a network in which layer $\ell$ was re-initialized is referred to as the re-initialization robustness of layer $\ell$.

-

Re-randomization: Re-sampling the layer’s parameters at random, $\theta^{(\ell)}_t \leftarrow \tilde{\theta}^{(\ell)} \sim \mathcal{P}^{(\ell)}$. The corresponding network performance is called the re-randomization robustness of layer $\ell$.

Layers can be categorized into two categories with the help of these two operations:

- Robust Layers: The network has no or only negligible performance degradation after re-initializing or re-randomizing the layer.

- Critical Layers: Otherwise.

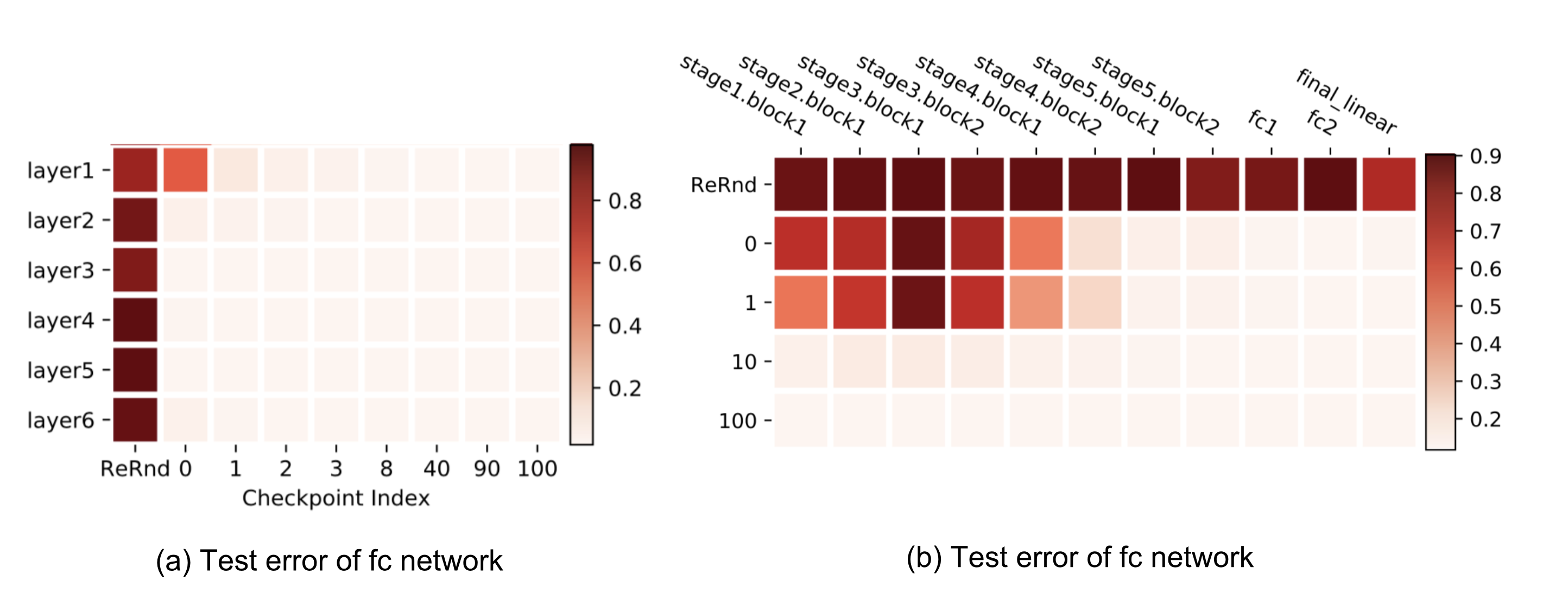

Similar patterns are observed on fully-connected and convolutional networks. Re-randomizing any of the layers completely destroys the model performance, as the prediction drops to random guessing immediately. More interestingly and surprisingly, when applying re-initialization, only the first or the first few layers (those closest to the input layer) are critical, while re-initializing higher levels causes only negligible decrease in performance.

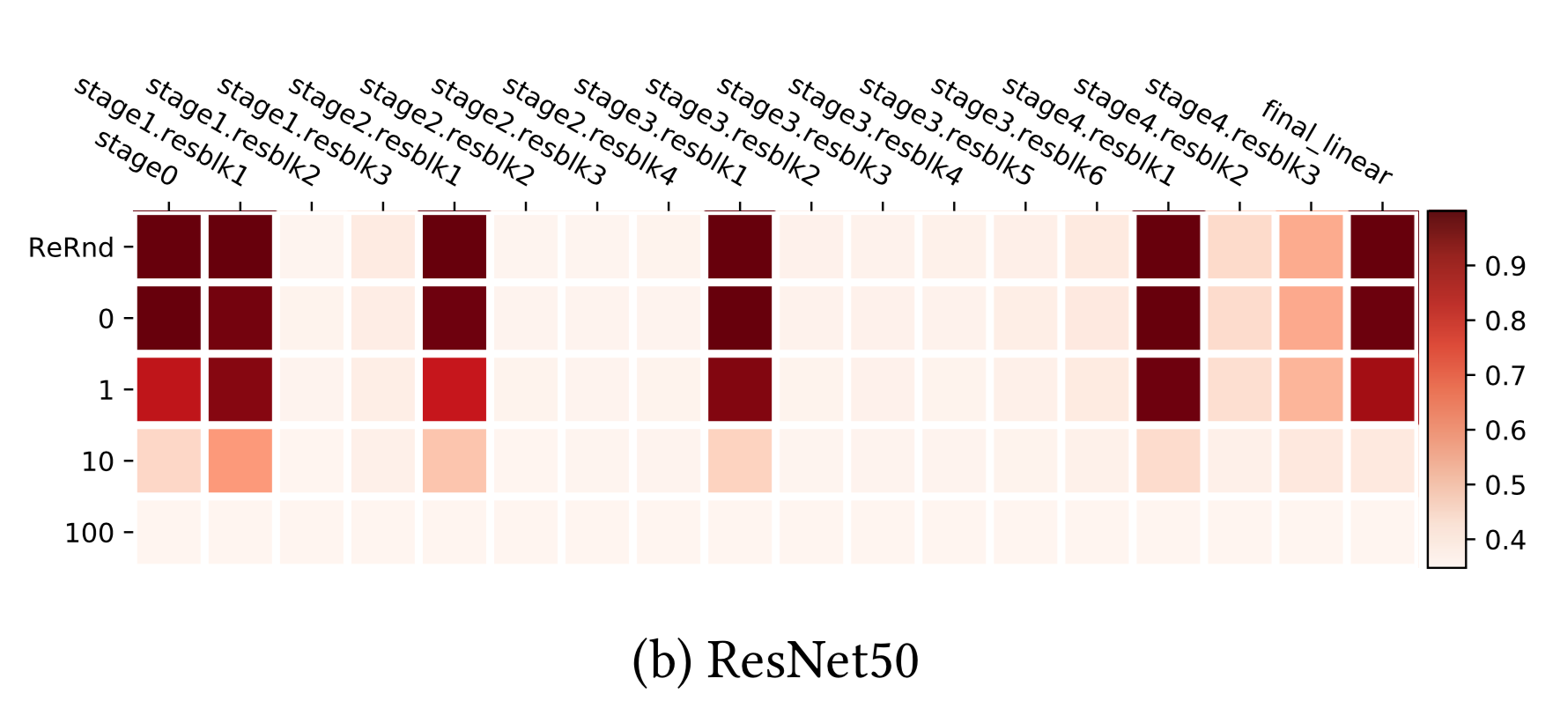

ResNet is able to use shortcuts between non-adjacent layers to re-distribute the sensitive layers across the networks rather than just at the bottom. With the help of residual block architecture, the network can evenly be robust to re-randomization. Only the first layer of each residual block is still sensitive to both re-initialization and re-randomization. If we consider each residual block as a local sub-network, the robustness pattern resembles the fc and conv nets above.

Based on the fact that many top layers in deep neural networks are not critical to the model performance after re-initialization, the paper loosely concluded that:

“Over-capacitated deep networks trained with stochastic gradient have low-complexity due to self-restricting the number of critical layers.”

We can consider re-initialization as a way to reduce the effective number of parameters, and thus the observation is aligned with what intrinsic dimension has demonstrated.

The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis

The lottery ticket hypothesis (Frankle & Carbin, 2019) is another intriguing and inspiring discovery, supporting that only a subset of network parameters have impact on the model performance and thus the network is not overfitted. The lottery ticket hypothesis states that a randomly initialized, dense, feed-forward network contains a pool of subnetworks and among them only a subset are “winning tickets” which can achieve the optimal performance when trained in isolation.

The idea is motivated by network pruning techniques — removing unnecessary weights (i.e. tiny weights that are almost negligible) without harming the model performance. Although the final network size can be reduced dramatically, it is hard to train such a pruned network architecture successfully from scratch. It feels like in order to successfully train a neural network, we need a large number of parameters, but we don’t need that many parameters to keep the accuracy high once the model is trained. Why is that?

The lottery ticket hypothesis did the following experiments:

- Randomly initialize a dense feed-forward network with initialization values $\theta_0$;

- Train the network for multiple iterations to achieve a good performance with parameter config $\theta$;

- Run pruning on $\theta$ and creating a mask $m$.

- The “winning ticket” initialization config is $m \odot \theta_0$.

Only training the small “winning ticket” subset of parameters with the initial values as found in step 1, the model is able to achieve the same level of accuracy as in step 2. It turns out a large parameter space is not needed in the final solution representation, but needed for training as it provides a big pool of initialization configs of many much smaller subnetworks.

The lottery ticket hypothesis opens a new perspective about interpreting and dissecting deep neural network results. Many interesting following-up works are on the way.

Experiments

After seeing all the interesting findings above, it should be pretty fun to reproduce them. Some results are easily to reproduce than others. Details are described below. My code is available on github lilianweng/generalization-experiment.

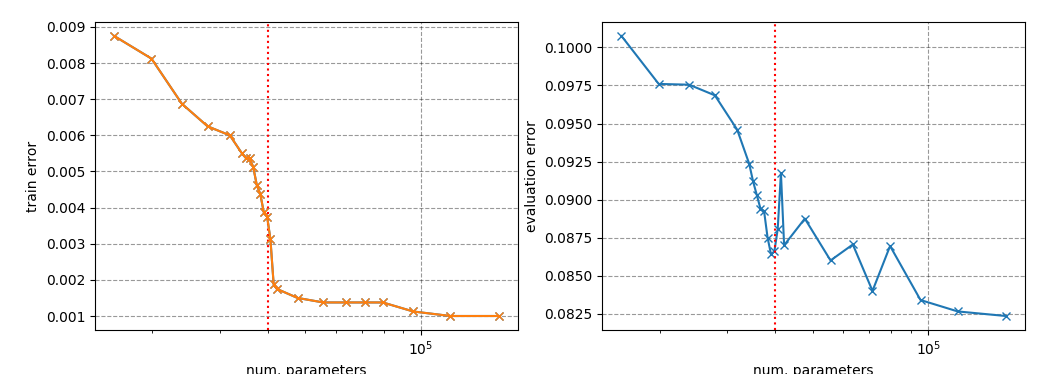

New Risk Curve for DL Models

This is the trickiest one to reproduce. The authors did give me a lot of good advice and I appreciate it a lot. Here are a couple of noticeable settings in their experiments:

- There are no regularization terms like weight decay, dropout.

- In Fig 3, the training set contains 4k samples. It is only sampled once and fixed for all the models. The evaluation uses the full MNIST test set.

- Each network is trained for a long time to achieve near-zero training risk. The learning rate is adjusted differently for models of different sizes.

- To make the model less sensitive to the initialization in the under-parameterization region, their experiments adopted a “weight reuse” scheme: the parameters obtained from training a smaller neural network are used as initialization for training larger networks.

I did not train or tune each model long enough to get perfect training performance, but evaluation error indeed shows a special twist around the interpolation threshold, different from training error. For example, for MNIST, the threshold is the number of training samples times the number of classes (10), that is 40000.

The x-axis is the number of model parameters: (28 * 28 + 1) * num. units + num. units * 10, in logarithm.

Layers are not Created Equal

This one is fairly easy to reproduce. See my implementation here.

In the first experiment, I used a three-layer fc networks with 256 units in each layer. Layer 0 is the input layer while layer 3 is the output. The network is trained on MNIST for 100 epochs.

In the second experiment, I used a four-layer fc networks with 128 units in each layer. Other settings are the same as experiment 1.

Intrinsic Dimension Measurement

To correctly map the $d$-dimensional subspace to the full parameter space, the projection matrix $\mathbf{P}$ should have orthogonal columns. Because the production $\mathbf{P}\theta^{(d)}$ is the sum of columns of $\mathbf{P}$ scaled by corresponding scalar values in the $d$-dim vector, $\sum_{i=1}^d \theta^{(d)}_i \mathbf{P}^\top_{(:,i)}$, it is better to fully utilize the subspace with orthogonal columns in $\mathbf{P}$.

My implementation follows a naive approach by sampling a large matrix with independent entries from a standard normal distribution. The columns are expected to be independent in a high dimension space and thus to be orthogonal. This works when the dimension is not too large. When exploring with a large $d$, there are methods for creating sparse projection matrices, which is what the intrinsic dimension paper suggested.

Here are experiment runs on two networks: (left) a two-layer fc network with 64 units in each layer and (right) a one-layer fc network with 128 hidden units, trained on 10% of MNIST. For every $d$, the model is trained for 100 epochs. See the code here.

Cited as:

@article{weng2019overfit,

title = "Are Deep Neural Networks Dramatically Overfitted?",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2019",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2019-03-14-overfit/"

}

References

[1] Wikipedia page on Occam’s Razor.

[2] Occam’s Razor on Principia Cybernetica Web.

[3] Peter Grunwald. “A Tutorial Introduction to the Minimum Description Length Principle”. 2004.

[4] Ian Goodfellow, et al. Deep Learning. 2016. Sec 6.4.1.

[5] Zhang, Chiyuan, et al. “Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization.” ICLR 2017.

[6] Shibani Santurkar, et al. “How does batch normalization help optimization?.” NIPS 2018.

[7] Mikhail Belkin, et al. “Reconciling modern machine learning and the bias-variance trade-off.” arXiv:1812.11118, 2018.

[8] Chiyuan Zhang, et al. “Are All Layers Created Equal?” arXiv:1902.01996, 2019.

[9] Chunyuan Li, et al. “Measuring the intrinsic dimension of objective landscapes.” ICLR 2018.

[10] Jonathan Frankle and Michael Carbin. “The lottery ticket hypothesis: Finding sparse, trainable neural networks.” ICLR 2019.