So far, I’ve written about two types of generative models, GAN and VAE. Neither of them explicitly learns the probability density function of real data, $p(\mathbf{x})$ (where $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{D}$) — because it is really hard! Taking the generative model with latent variables as an example, $p(\mathbf{x}) = \int p(\mathbf{x}\vert\mathbf{z})p(\mathbf{z})d\mathbf{z}$ can hardly be calculated as it is intractable to go through all possible values of the latent code $\mathbf{z}$.

Flow-based deep generative models conquer this hard problem with the help of normalizing flows, a powerful statistics tool for density estimation. A good estimation of $p(\mathbf{x})$ makes it possible to efficiently complete many downstream tasks: sample unobserved but realistic new data points (data generation), predict the rareness of future events (density estimation), infer latent variables, fill in incomplete data samples, etc.

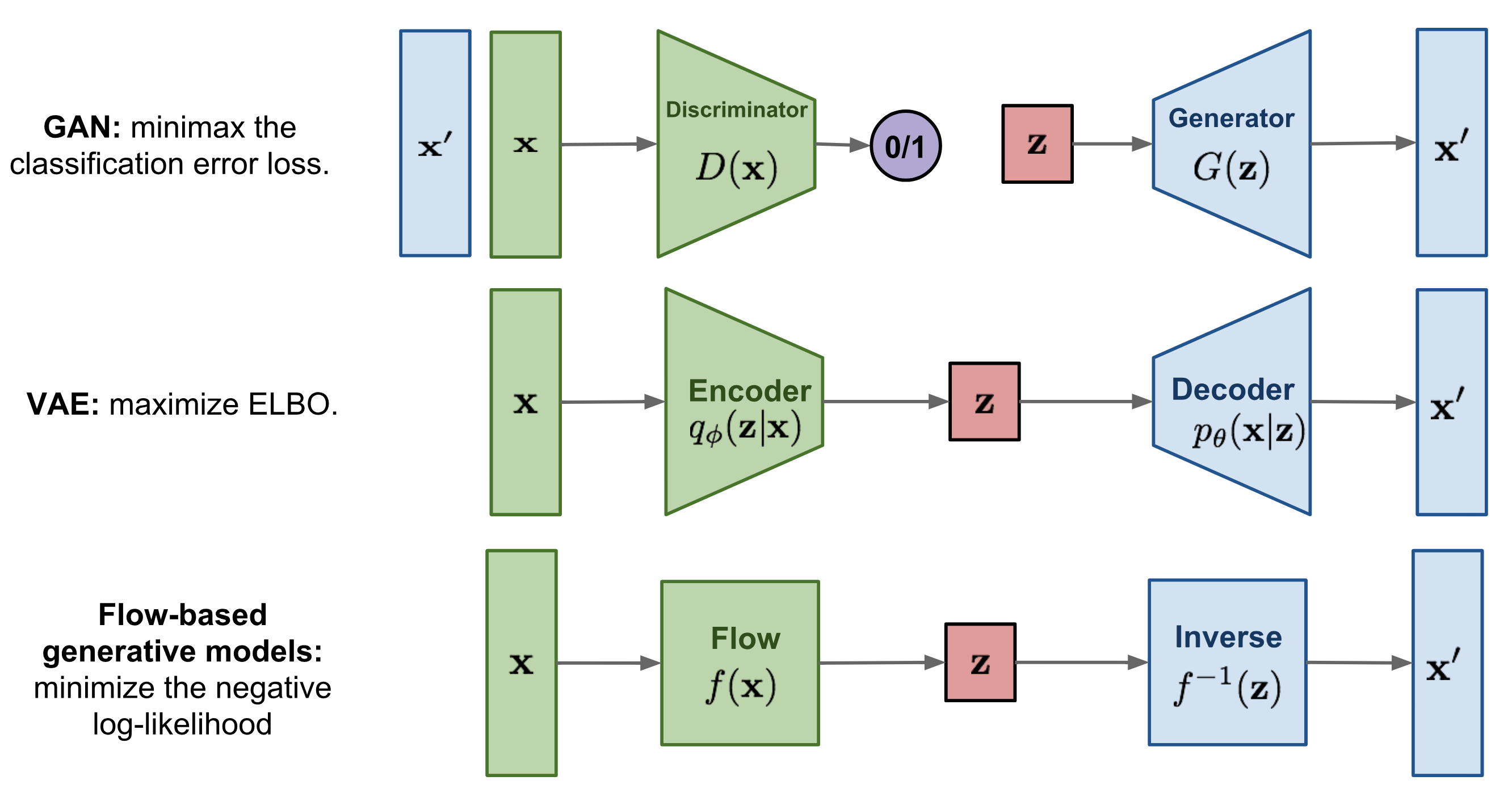

Types of Generative Models

Here is a quick summary of the difference between GAN, VAE, and flow-based generative models:

- Generative adversarial networks: GAN provides a smart solution to model the data generation, an unsupervised learning problem, as a supervised one. The discriminator model learns to distinguish the real data from the fake samples that are produced by the generator model. Two models are trained as they are playing a minimax game.

- Variational autoencoders: VAE inexplicitly optimizes the log-likelihood of the data by maximizing the evidence lower bound (ELBO).

- Flow-based generative models: A flow-based generative model is constructed by a sequence of invertible transformations. Unlike other two, the model explicitly learns the data distribution $p(\mathbf{x})$ and therefore the loss function is simply the negative log-likelihood.

Linear Algebra Basics Recap

We should understand two key concepts before getting into the flow-based generative model: the Jacobian determinant and the change of variable rule. Pretty basic, so feel free to skip.

Jacobian Matrix and Determinant

Given a function of mapping a $n$-dimensional input vector $\mathbf{x}$ to a $m$-dimensional output vector, $\mathbf{f}: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}^m$, the matrix of all first-order partial derivatives of this function is called the Jacobian matrix, $\mathbf{J}$ where one entry on the i-th row and j-th column is $\mathbf{J}_{ij} = \frac{\partial f_i}{\partial x_j}$.

The determinant is one real number computed as a function of all the elements in a squared matrix. Note that the determinant only exists for square matrices. The absolute value of the determinant can be thought of as a measure of “how much multiplication by the matrix expands or contracts space”.

The determinant of a nxn matrix $M$ is:

where the subscript under the summation $j_1 j_2 \dots j_n$ are all permutations of the set {1, 2, …, n}, so there are $n!$ items in total; $\tau(.)$ indicates the signature of a permutation.

The determinant of a square matrix $M$ detects whether it is invertible: If $\det(M)=0$ then $M$ is not invertible (a singular matrix with linearly dependent rows or columns; or any row or column is all 0); otherwise, if $\det(M)\neq 0$, $M$ is invertible.

The determinant of the product is equivalent to the product of the determinants: $\det(AB) = \det(A)\det(B)$. (proof)

Change of Variable Theorem

Let’s review the change of variable theorem specifically in the context of probability density estimation, starting with a single variable case.

Given a random variable $z$ and its known probability density function $z \sim \pi(z)$, we would like to construct a new random variable using a 1-1 mapping function $x = f(z)$. The function $f$ is invertible, so $z=f^{-1}(x)$. Now the question is how to infer the unknown probability density function of the new variable, $p(x)$?

By definition, the integral $\int \pi(z)dz$ is the sum of an infinite number of rectangles of infinitesimal width $\Delta z$. The height of such a rectangle at position $z$ is the value of the density function $\pi(z)$. When we substitute the variable, $z = f^{-1}(x)$ yields $\frac{\Delta z}{\Delta x} = (f^{-1}(x))’$ and $\Delta z = (f^{-1}(x))’ \Delta x$. Here $\vert(f^{-1}(x))’\vert$ indicates the ratio between the area of rectangles defined in two different coordinate of variables $z$ and $x$ respectively.

The multivariable version has a similar format:

where $\det \frac{\partial f}{\partial\mathbf{z}}$ is the Jacobian determinant of the function $f$. The full proof of the multivariate version is out of the scope of this post; ask Google if interested ;)

What is Normalizing Flows?

Being able to do good density estimation has direct applications in many machine learning problems, but it is very hard. For example, since we need to run backward propagation in deep learning models, the embedded probability distribution (i.e. posterior $p(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$) is expected to be simple enough to calculate the derivative easily and efficiently. That is why Gaussian distribution is often used in latent variable generative models, even though most of real world distributions are much more complicated than Gaussian.

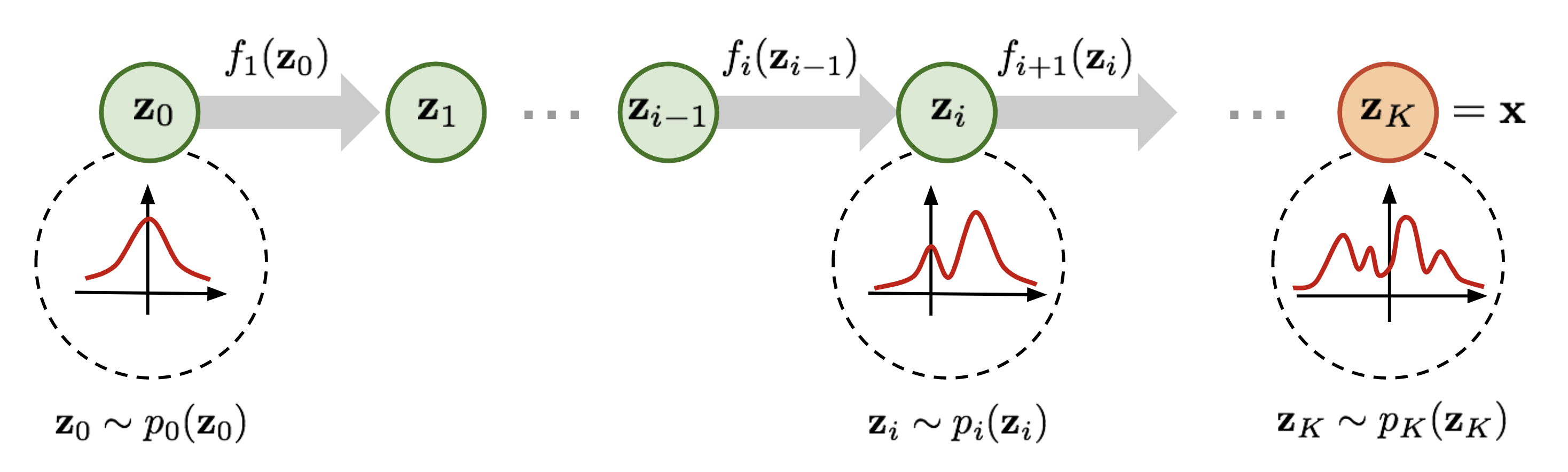

Here comes a Normalizing Flow (NF) model for better and more powerful distribution approximation. A normalizing flow transforms a simple distribution into a complex one by applying a sequence of invertible transformation functions. Flowing through a chain of transformations, we repeatedly substitute the variable for the new one according to the change of variables theorem and eventually obtain a probability distribution of the final target variable.

As defined in Fig. 2,

Then let’s convert the equation to be a function of $\mathbf{z}_i$ so that we can do inference with the base distribution.

(*) A note on the “inverse function theorem”: If $y=f(x)$ and $x=f^{-1}(y)$, we have:

(*) A note on “Jacobians of invertible function”: The determinant of the inverse of an invertible matrix is the inverse of the determinant: $\det(M^{-1}) = (\det(M))^{-1}$, because $\det(M)\det(M^{-1}) = \det(M \cdot M^{-1}) = \det(I) = 1$.

Given such a chain of probability density functions, we know the relationship between each pair of consecutive variables. We can expand the equation of the output $\mathbf{x}$ step by step until tracing back to the initial distribution $\mathbf{z}_0$.

The path traversed by the random variables $\mathbf{z}_i = f_i(\mathbf{z}_{i-1})$ is the flow and the full chain formed by the successive distributions $\pi_i$ is called a normalizing flow. Required by the computation in the equation, a transformation function $f_i$ should satisfy two properties:

- It is easily invertible.

- Its Jacobian determinant is easy to compute.

Models with Normalizing Flows

With normalizing flows in our toolbox, the exact log-likelihood of input data $\log p(\mathbf{x})$ becomes tractable. As a result, the training criterion of flow-based generative model is simply the negative log-likelihood (NLL) over the training dataset $\mathcal{D}$:

RealNVP

The RealNVP (Real-valued Non-Volume Preserving; Dinh et al., 2017) model implements a normalizing flow by stacking a sequence of invertible bijective transformation functions. In each bijection $f: \mathbf{x} \mapsto \mathbf{y}$, known as affine coupling layer, the input dimensions are split into two parts:

- The first $d$ dimensions stay same;

- The second part, $d+1$ to $D$ dimensions, undergo an affine transformation (“scale-and-shift”) and both the scale and shift parameters are functions of the first $d$ dimensions.

where $s(.)$ and $t(.)$ are scale and translation functions and both map $\mathbb{R}^d \mapsto \mathbb{R}^{D-d}$. The $\odot$ operation is the element-wise product.

Now let’s check whether this transformation satisfy two basic properties for a flow transformation.

Condition 1: “It is easily invertible.”

Yes and it is fairly straightforward.

Condition 2: “Its Jacobian determinant is easy to compute.”

Yes. It is not hard to get the Jacobian matrix and determinant of this transformation. The Jacobian is a lower triangular matrix.

Hence the determinant is simply the product of terms on the diagonal.

So far, the affine coupling layer looks perfect for constructing a normalizing flow :)

Even better, since (i) computing $f^-1$ does not require computing the inverse of $s$ or $t$ and (ii) computing the Jacobian determinant does not involve computing the Jacobian of $s$ or $t$, those functions can be arbitrarily complex; i.e. both $s$ and $t$ can be modeled by deep neural networks.

In one affine coupling layer, some dimensions (channels) remain unchanged. To make sure all the inputs have a chance to be altered, the model reverses the ordering in each layer so that different components are left unchanged. Following such an alternating pattern, the set of units which remain identical in one transformation layer are always modified in the next. Batch normalization is found to help training models with a very deep stack of coupling layers.

Furthermore, RealNVP can work in a multi-scale architecture to build a more efficient model for large inputs. The multi-scale architecture applies several “sampling” operations to normal affine layers, including spatial checkerboard pattern masking, squeezing operation, and channel-wise masking. Read the paper for more details on the multi-scale architecture.

NICE

The NICE (Non-linear Independent Component Estimation; Dinh, et al. 2015) model is a predecessor of RealNVP. The transformation in NICE is the affine coupling layer without the scale term, known as additive coupling layer.

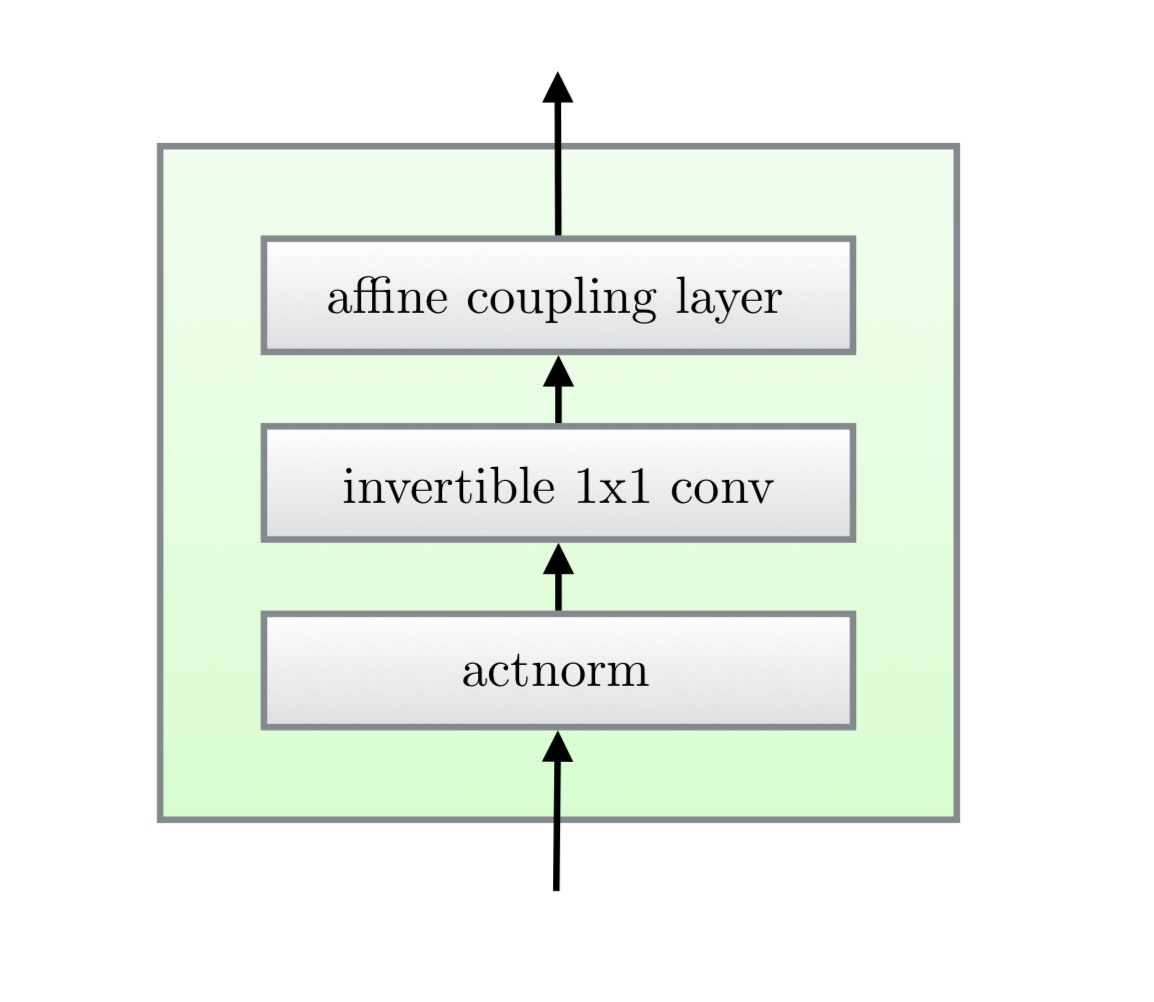

Glow

The Glow (Kingma and Dhariwal, 2018) model extends the previous reversible generative models, NICE and RealNVP, and simplifies the architecture by replacing the reverse permutation operation on the channel ordering with invertible 1x1 convolutions.

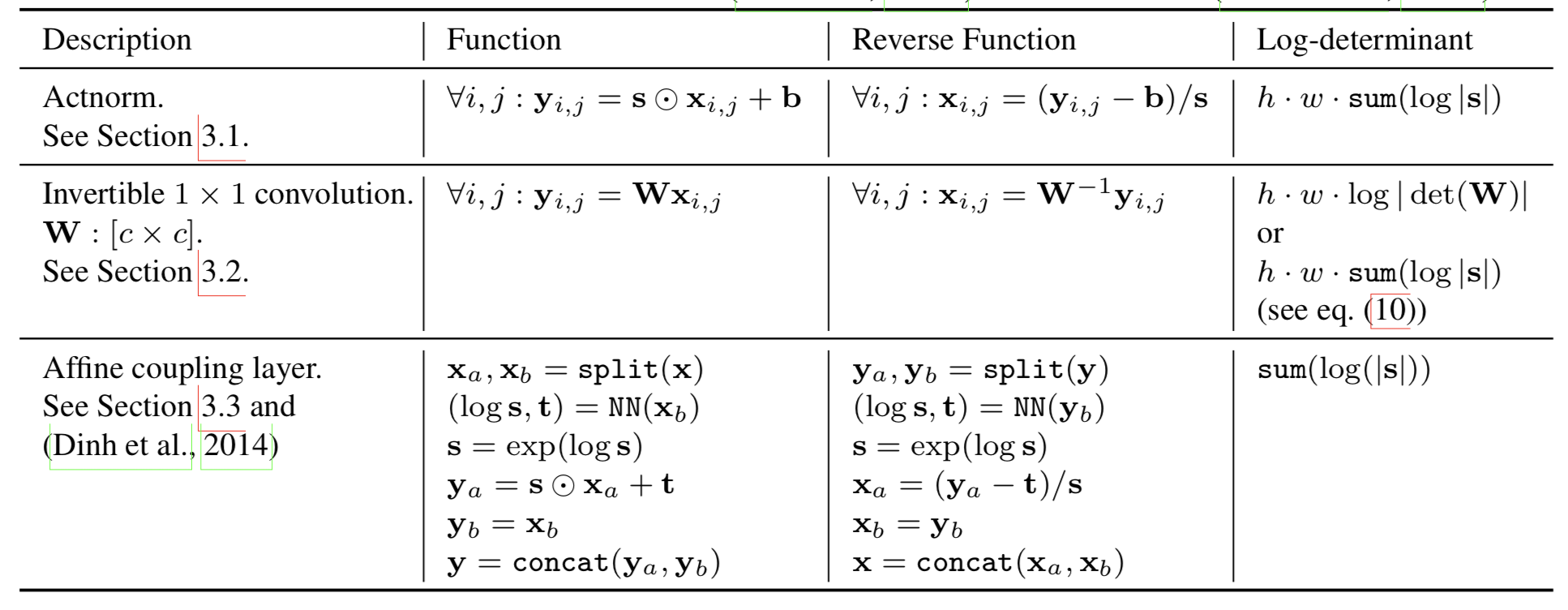

There are three substeps in one step of flow in Glow.

Substep 1: Activation normalization (short for “actnorm”)

It performs an affine transformation using a scale and bias parameter per channel, similar to batch normalization, but works for mini-batch size 1. The parameters are trainable but initialized so that the first minibatch of data have mean 0 and standard deviation 1 after actnorm.

Substep 2: Invertible 1x1 conv

Between layers of the RealNVP flow, the ordering of channels is reversed so that all the data dimensions have a chance to be altered. A 1×1 convolution with equal number of input and output channels is a generalization of any permutation of the channel ordering.

Say, we have an invertible 1x1 convolution of an input $h \times w \times c$ tensor $\mathbf{h}$ with a weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$ of size $c \times c$. The output is a $h \times w \times c$ tensor, labeled as $f = \texttt{conv2d}(\mathbf{h}; \mathbf{W})$. In order to apply the change of variable rule, we need to compute the Jacobian determinant $\vert \det\partial f / \partial\mathbf{h}\vert$.

Both the input and output of 1x1 convolution here can be viewed as a matrix of size $h \times w$. Each entry $\mathbf{x}_{ij}$ ($i=1,\dots,h, j=1,\dots,w$) in $\mathbf{h}$ is a vector of $c$ channels and each entry is multiplied by the weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$ to obtain the corresponding entry $\mathbf{y}_{ij}$ in the output matrix respectively. The derivative of each entry is $\partial \mathbf{x}_{ij} \mathbf{W} / \partial\mathbf{x}_{ij} = \mathbf{W}$ and there are $h \times w$ such entries in total:

The inverse 1x1 convolution depends on the inverse matrix $\mathbf{W}^{-1}$. Since the weight matrix is relatively small, the amount of computation for the matrix determinant (tf.linalg.det) and inversion (tf.linalg.inv) is still under control.

Substep 3: Affine coupling layer

The design is same as in RealNVP.

Models with Autoregressive Flows

The autoregressive constraint is a way to model sequential data, $\mathbf{x} = [x_1, \dots, x_D]$: each output only depends on the data observed in the past, but not on the future ones. In other words, the probability of observing $x_i$ is conditioned on $x_1, \dots, x_{i-1}$ and the product of these conditional probabilities gives us the probability of observing the full sequence:

How to model the conditional density is of your choice. It can be a univariate Gaussian with mean and standard deviation computed as a function of $x_{1:i-1}$, or a multilayer neural network with $x_{1:i-1}$ as the input.

If a flow transformation in a normalizing flow is framed as an autoregressive model — each dimension in a vector variable is conditioned on the previous dimensions — this is an autoregressive flow.

This section starts with several classic autoregressive models (MADE, PixelRNN, WaveNet) and then we dive into autoregressive flow models (MAF and IAF).

MADE

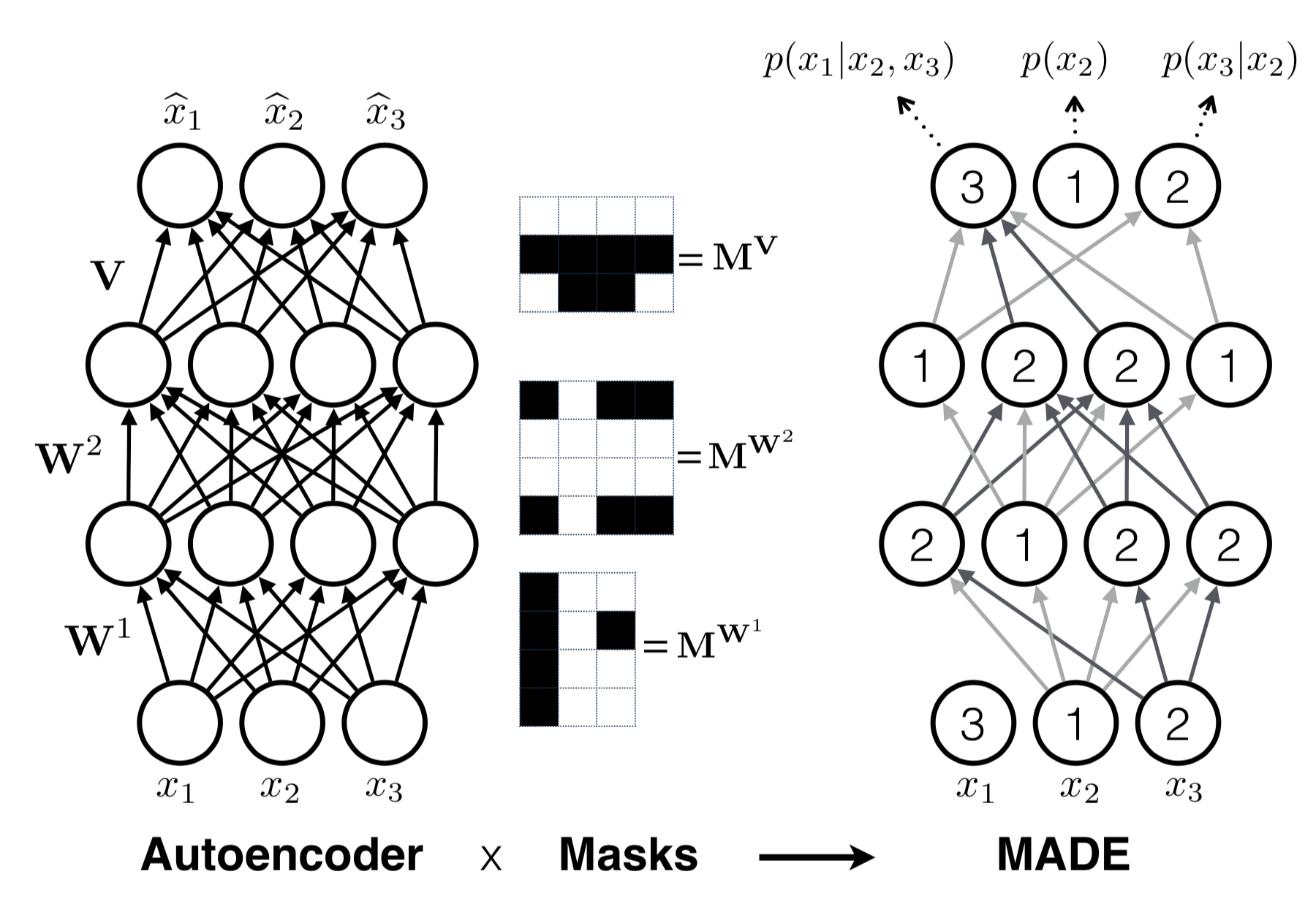

MADE (Masked Autoencoder for Distribution Estimation; Germain et al., 2015) is a specially designed architecture to enforce the autoregressive property in the autoencoder efficiently. When using an autoencoder to predict the conditional probabilities, rather than feeding the autoencoder with input of different observation windows $D$ times, MADE removes the contribution from certain hidden units by multiplying binary mask matrices so that each input dimension is reconstructed only from previous dimensions in a given ordering in a single pass.

In a multilayer fully-connected neural network, say, we have $L$ hidden layers with weight matrices $\mathbf{W}^1, \dots, \mathbf{W}^L$ and an output layer with weight matrix $\mathbf{V}$. The output $\hat{\mathbf{x}}$ has each dimension $\hat{x}_i = p(x_i\vert x_{1:i-1})$.

Without any mask, the computation through layers looks like the following:

To zero out some connections between layers, we can simply element-wise multiply every weight matrix by a binary mask matrix. Each hidden node is assigned with a random “connectivity integer” between $1$ and $D-1$; the assigned value for the $k$-th unit in the $l$-th layer is denoted by $m^l_k$. The binary mask matrix is determined by element-wise comparing values of two nodes in two layers.

A unit in the current layer can only be connected to other units with equal or smaller numbers in the previous layer and this type of dependency easily propagates through the network up to the output layer. Once the numbers are assigned to all the units and layers, the ordering of input dimensions is fixed and the conditional probability is produced with respect to it. See a great illustration in To make sure all the hidden units are connected to the input and output layers through some paths, the $m^l_k$ is sampled to be equal or greater than the minimal connectivity integer in the previous layer, $\min_{k’} m_{k’}^{l-1}$.

MADE training can be further facilitated by:

- Order-agnostic training: shuffle the input dimensions, so that MADE is able to model any arbitrary ordering; can create an ensemble of autoregressive models at the runtime.

- Connectivity-agnostic training: to avoid a model being tied up to a specific connectivity pattern constraints, resample $m^l_k$ for each training minibatch.

PixelRNN

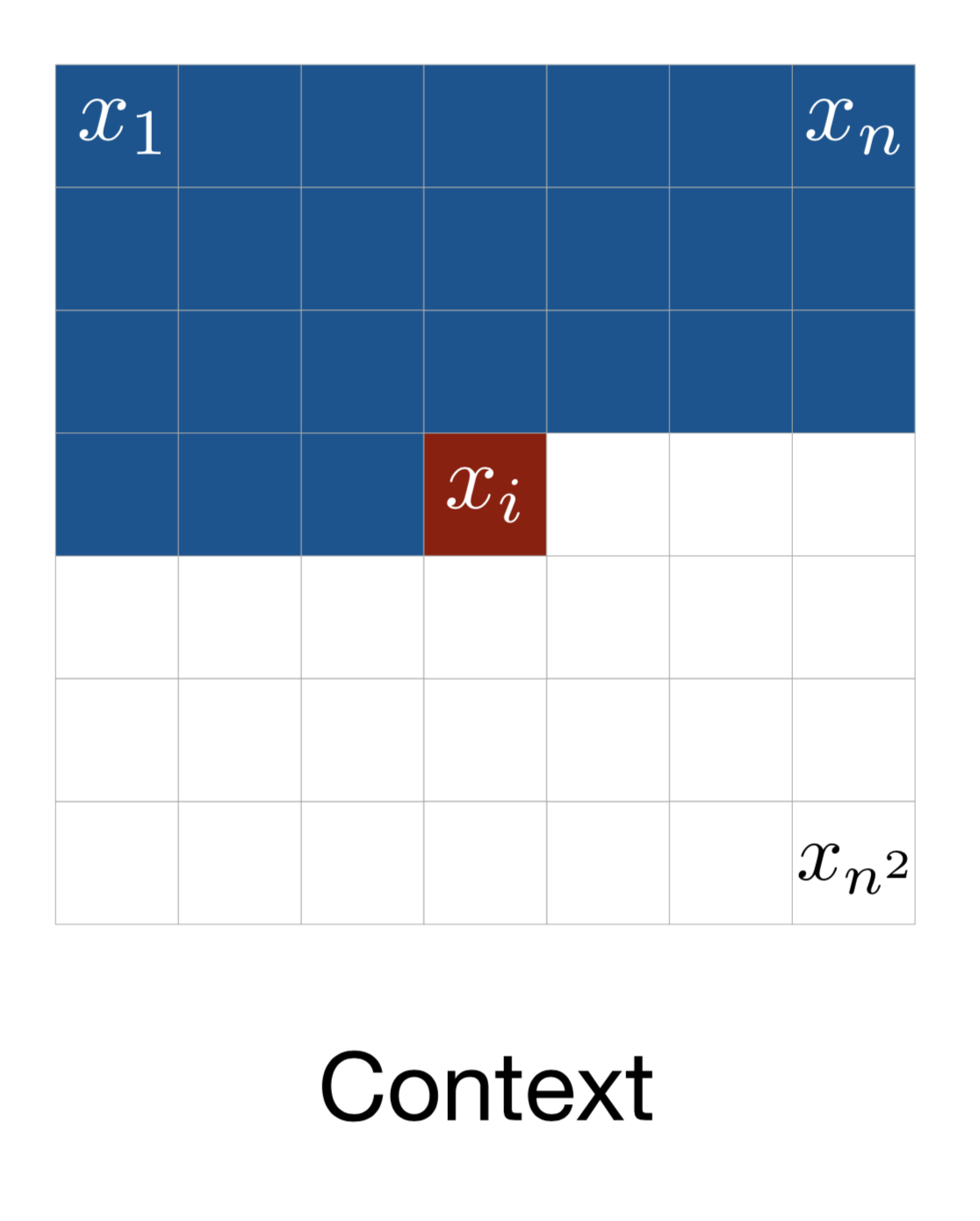

PixelRNN (Oord et al, 2016) is a deep generative model for images. The image is generated one pixel at a time and each new pixel is sampled conditional on the pixels that have been seen before.

Let’s consider an image of size $n \times n$, $\mathbf{x} = \{x_1, \dots, x_{n^2}\}$, the model starts generating pixels from the top left corner, from left to right and top to bottom (See Fig. 6).

Every pixel $x_i$ is sampled from a probability distribution conditional over the the past context: pixels above it or on the left of it when in the same row. The definition of such context looks pretty arbitrary, because how visual attention is attended to an image is more flexible. Somehow magically a generative model with such a strong assumption works.

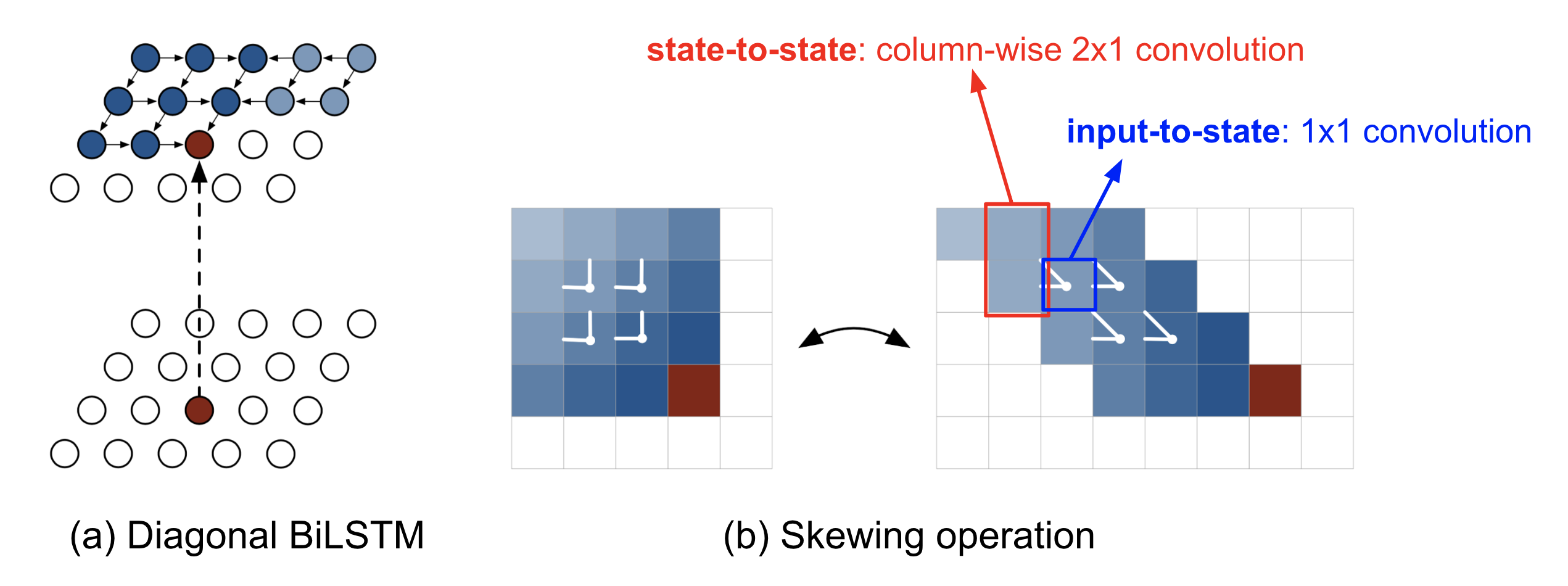

One implementation that could capture the entire context is the Diagonal BiLSTM. First, apply the skewing operation by offsetting each row of the input feature map by one position with respect to the previous row, so that computation for each row can be parallelized. Then the LSTM states are computed with respect to the current pixel and the pixels on the left.

where $\circledast$ denotes the convolution operation and $\odot$ is the element-wise multiplication. The input-to-state component $\mathbf{K}^{is}$ is a 1x1 convolution, while the state-to-state recurrent component is computed with a column-wise convolution $\mathbf{K}^{ss}$ with a kernel of size 2x1.

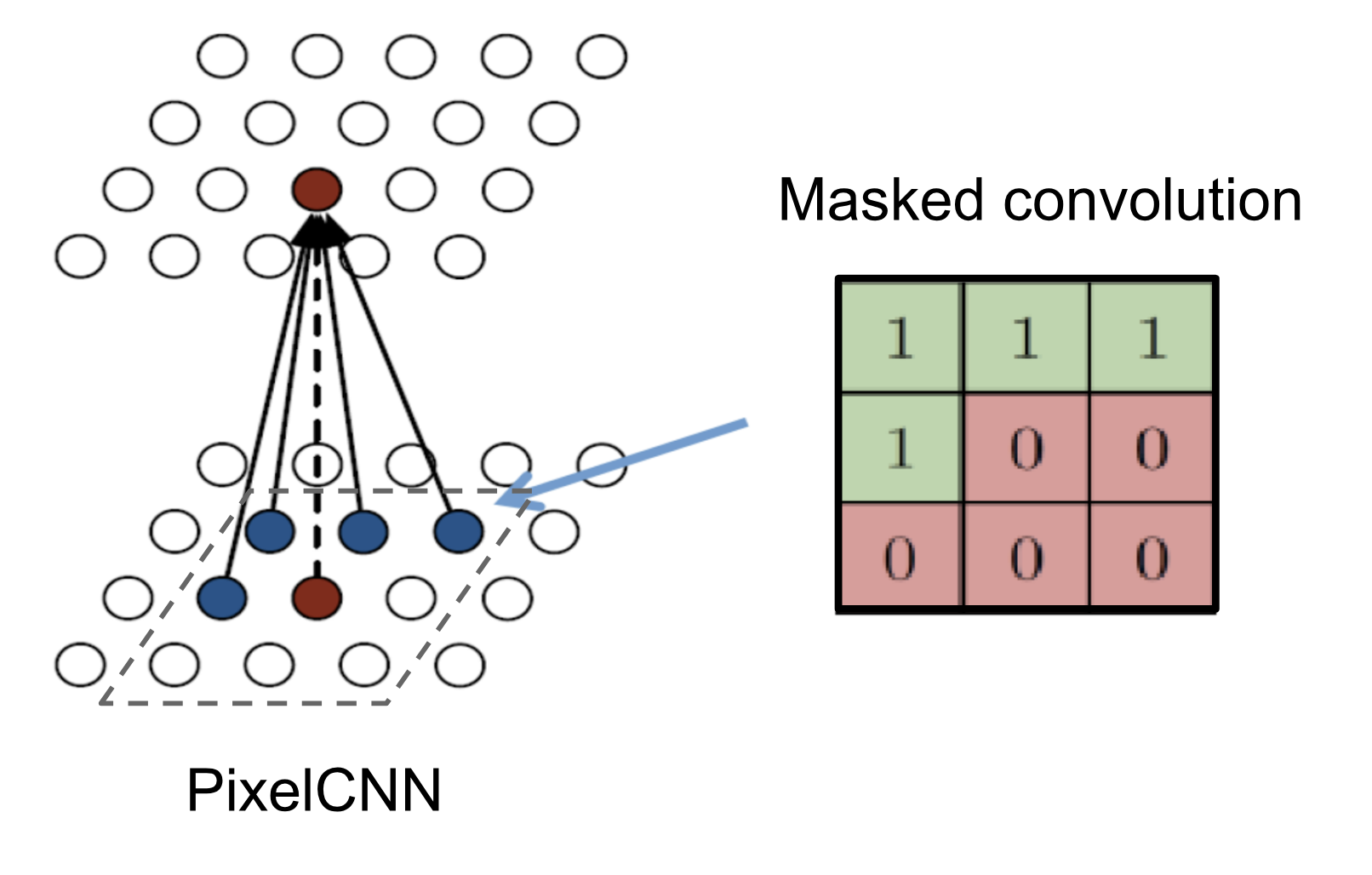

The diagonal BiLSTM layers are capable of processing an unbounded context field, but expensive to compute due to the sequential dependency between states. A faster implementation uses multiple convolutional layers without pooling to define a bounded context box. The convolution kernel is masked so that the future context is not seen, similar to MADE. This convolution version is called PixelCNN.

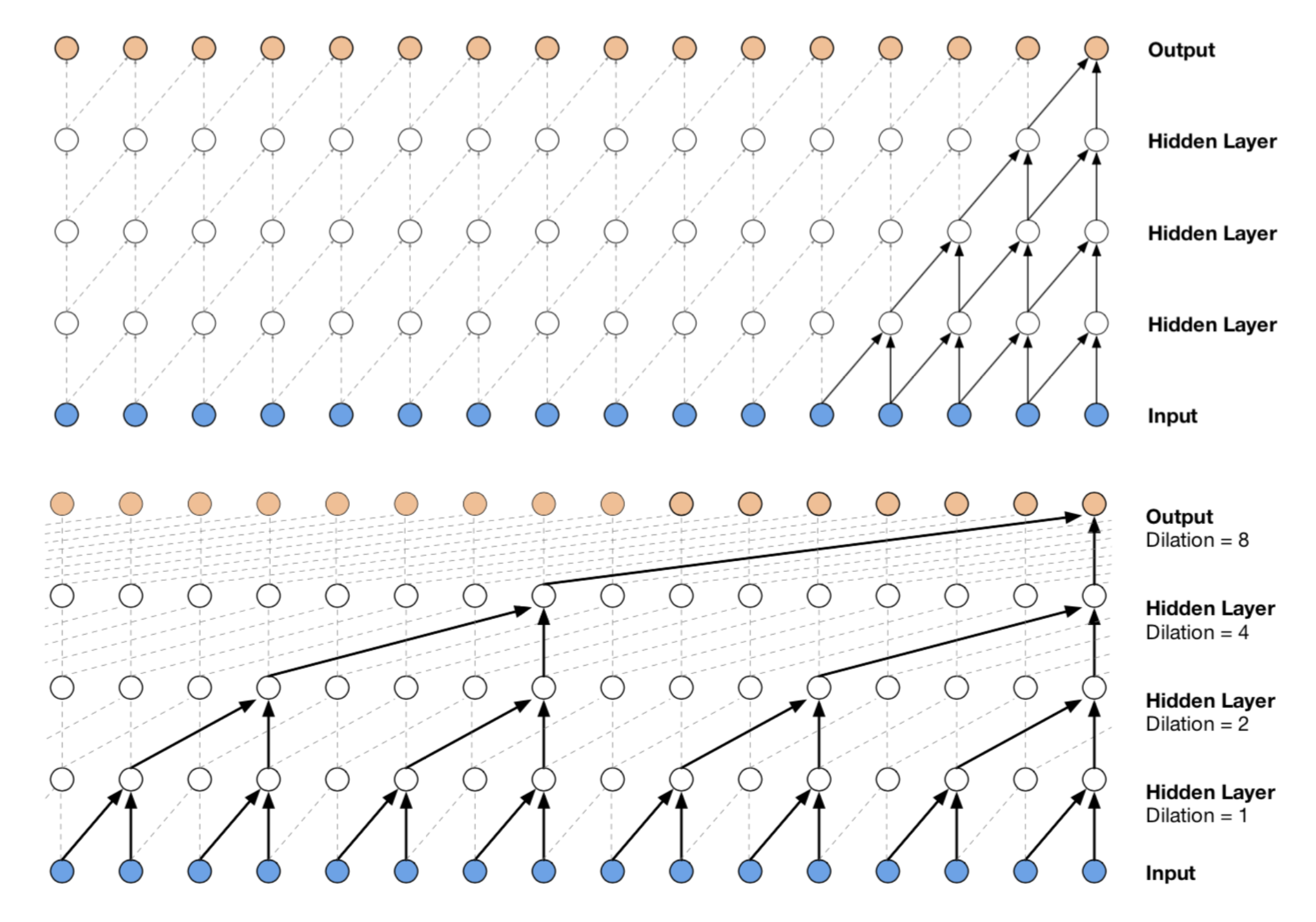

WaveNet

WaveNet (Van Den Oord, et al. 2016) is very similar to PixelCNN but applied to 1-D audio signals. WaveNet consists of a stack of causal convolution which is a convolution operation designed to respect the ordering: the prediction at a certain timestamp can only consume the data observed in the past, no dependency on the future. In PixelCNN, the causal convolution is implemented by masked convolution kernel. The causal convolution in WaveNet is simply to shift the output by a number of timestamps to the future so that the output is aligned with the last input element.

One big drawback of convolution layer is a very limited size of receptive field. The output can hardly depend on the input hundreds or thousands of timesteps ago, which can be a crucial requirement for modeling long sequences. WaveNet therefore adopts dilated convolution (animation), where the kernel is applied to an evenly-distributed subset of samples in a much larger receptive field of the input.

WaveNet uses the gated activation unit as the non-linear layer, as it is found to work significantly better than ReLU for modeling 1-D audio data. The residual connection is applied after the gated activation.

where $\mathbf{W}_{f,k}$ and $\mathbf{W}_{g,k}$ are convolution filter and gate weight matrix of the $k$-th layer, respectively; both are learnable.

Masked Autoregressive Flow

Masked Autoregressive Flow (MAF; Papamakarios et al., 2017) is a type of normalizing flows, where the transformation layer is built as an autoregressive neural network. MAF is very similar to Inverse Autoregressive Flow (IAF) introduced later. See more discussion on the relationship between MAF and IAF in the next section.

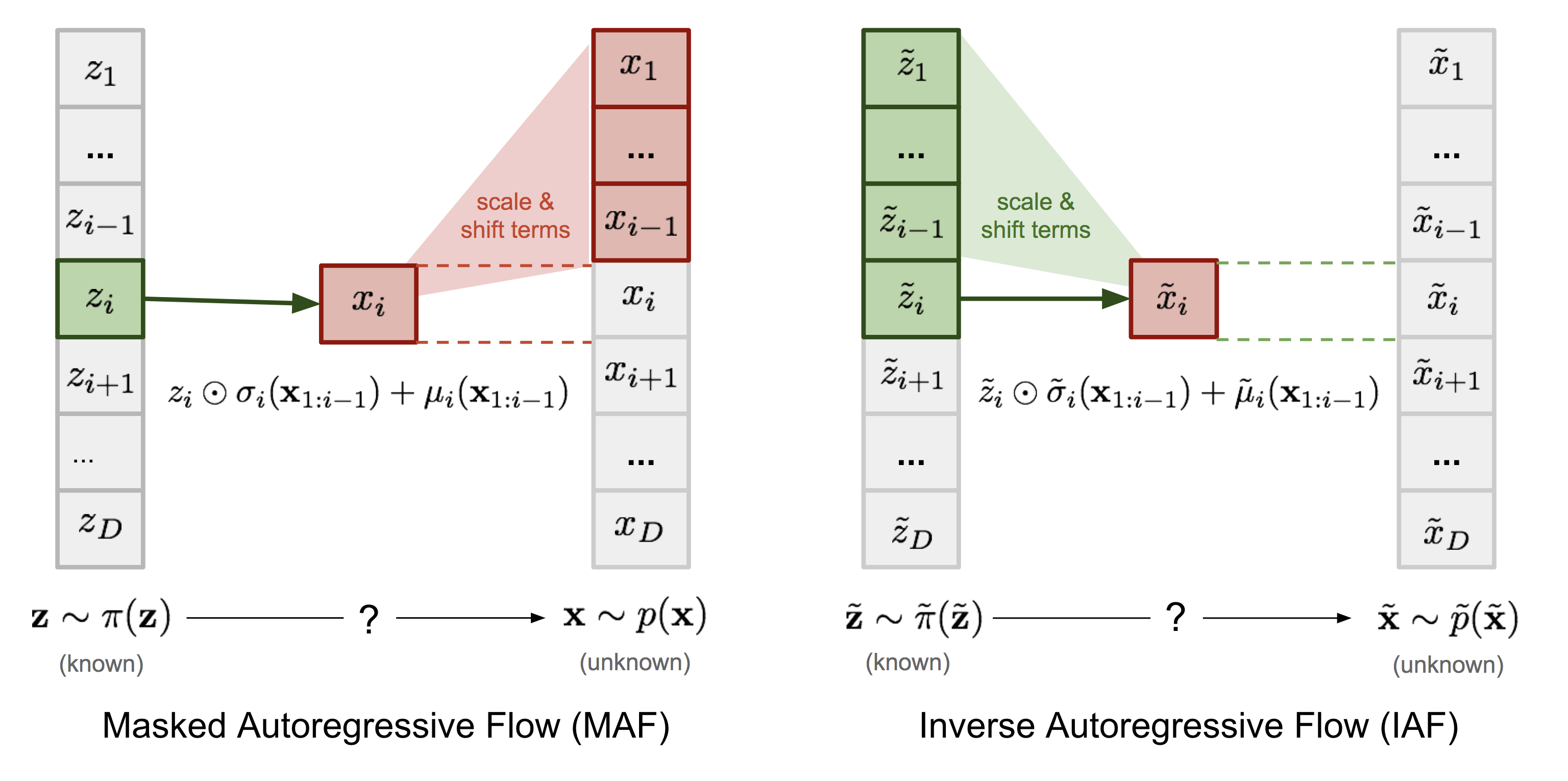

Given two random variables, $\mathbf{z} \sim \pi(\mathbf{z})$ and $\mathbf{x} \sim p(\mathbf{x})$ and the probability density function $\pi(\mathbf{z})$ is known, MAF aims to learn $p(\mathbf{x})$. MAF generates each $x_i$ conditioned on the past dimensions $\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1}$.

Precisely the conditional probability is an affine transformation of $\mathbf{z}$, where the scale and shift terms are functions of the observed part of $\mathbf{x}$.

- Data generation, producing a new $\mathbf{x}$:

$x_i \sim p(x_i\vert\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1}) = z_i \odot \sigma_i(\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1}) + \mu_i(\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1})\text{, where }\mathbf{z} \sim \pi(\mathbf{z})$

- Density estimation, given a known $\mathbf{x}$:

$p(\mathbf{x}) = \prod_{i=1}^D p(x_i\vert\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1})$

The generation procedure is sequential, so it is slow by design. While density estimation only needs one pass the network using architecture like MADE. The transformation function is trivial to inverse and the Jacobian determinant is easy to compute too.

Inverse Autoregressive Flow

Similar to MAF, Inverse autoregressive flow (IAF; Kingma et al., 2016) models the conditional probability of the target variable as an autoregressive model too, but with a reversed flow, thus achieving a much efficient sampling process.

First, let’s reverse the affine transformation in MAF:

If let:

Then we would have,

IAF intends to estimate the probability density function of $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ given that $\tilde{\pi}(\tilde{\mathbf{z}})$ is already known. The inverse flow is an autoregressive affine transformation too, same as in MAF, but the scale and shift terms are autoregressive functions of observed variables from the known distribution $\tilde{\pi}(\tilde{\mathbf{z}})$. See the comparison between MAF and IAF in

Computations of the individual elements $\tilde{x}_i$ do not depend on each other, so they are easily parallelizable (only one pass using MADE). The density estimation for a known $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ is not efficient, because we have to recover the value of $\tilde{z}_i$ in a sequential order, $\tilde{z}_i = (\tilde{x}_i - \tilde{\mu}_i(\tilde{\mathbf{z}}_{1:i-1})) / \tilde{\sigma}_i(\tilde{\mathbf{z}}_{1:i-1})$, thus D times in total.

| Base distribution | Target distribution | Model | Data generation | Density estimation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF | $\mathbf{z}\sim\pi(\mathbf{z})$ | $\mathbf{x}\sim p(\mathbf{x})$ | $x_i = z_i \odot \sigma_i(\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1}) + \mu_i(\mathbf{x}_{1:i-1})$ | Sequential; slow | One pass; fast |

| IAF | $\tilde{\mathbf{z}}\sim\tilde{\pi}(\tilde{\mathbf{z}})$ | $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}\sim\tilde{p}(\tilde{\mathbf{x}})$ | $\tilde{x}_i = \tilde{z}_i \odot \tilde{\sigma}_i(\tilde{\mathbf{z}}_{1:i-1}) + \tilde{\mu}_i(\tilde{\mathbf{z}}_{1:i-1})$ | One pass; fast | Sequential; slow |

| ———- | ———- | ———- | ———- | ———- | ———- |

VAE + Flows

In Variational Autoencoder, if we want to model the posterior $p(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$ as a more complicated distribution rather than simple Gaussian. Intuitively we can use normalizing flow to transform the base Gaussian for better density approximation. The encoder then would predict a set of scale and shift terms $(\mu_i, \sigma_i)$ which are all functions of input $\mathbf{x}$. Read the paper for more details if interested.

If you notice mistakes and errors in this post, don’t hesitate to contact me at [lilian dot wengweng at gmail dot com] and I would be very happy to correct them right away!

See you in the next post :D

Cited as:

@article{weng2018flow,

title = "Flow-based Deep Generative Models",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2018",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2018-10-13-flow-models/"

}

Reference

[1] Danilo Jimenez Rezende, and Shakir Mohamed. “Variational inference with normalizing flows.” ICML 2015.

[2] Normalizing Flows Tutorial, Part 1: Distributions and Determinants by Eric Jang.

[3] Normalizing Flows Tutorial, Part 2: Modern Normalizing Flows by Eric Jang.

[4] Normalizing Flows by Adam Kosiorek.

[5] Laurent Dinh, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, and Samy Bengio. “Density estimation using Real NVP.” ICLR 2017.

[6] Laurent Dinh, David Krueger, and Yoshua Bengio. “NICE: Non-linear independent components estimation.” ICLR 2015 Workshop track.

[7] Diederik P. Kingma, and Prafulla Dhariwal. “Glow: Generative flow with invertible 1x1 convolutions.” arXiv:1807.03039 (2018).

[8] Germain, Mathieu, Karol Gregor, Iain Murray, and Hugo Larochelle. “Made: Masked autoencoder for distribution estimation.” ICML 2015.

[9] Aaron van den Oord, Nal Kalchbrenner, and Koray Kavukcuoglu. “Pixel recurrent neural networks.” ICML 2016.

[10] Diederik P. Kingma, et al. “Improved variational inference with inverse autoregressive flow.” NIPS. 2016.

[11] George Papamakarios, Iain Murray, and Theo Pavlakou. “Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation.” NIPS 2017.

[12] Jianlin Su, and Guang Wu. “f-VAEs: Improve VAEs with Conditional Flows.” arXiv:1809.05861 (2018).

[13] Van Den Oord, Aaron, et al. “WaveNet: A generative model for raw audio.” SSW. 2016.