[Updated on 2019-07-18: add a section on VQ-VAE & VQ-VAE-2.]

[Updated on 2019-07-26: add a section on TD-VAE.]

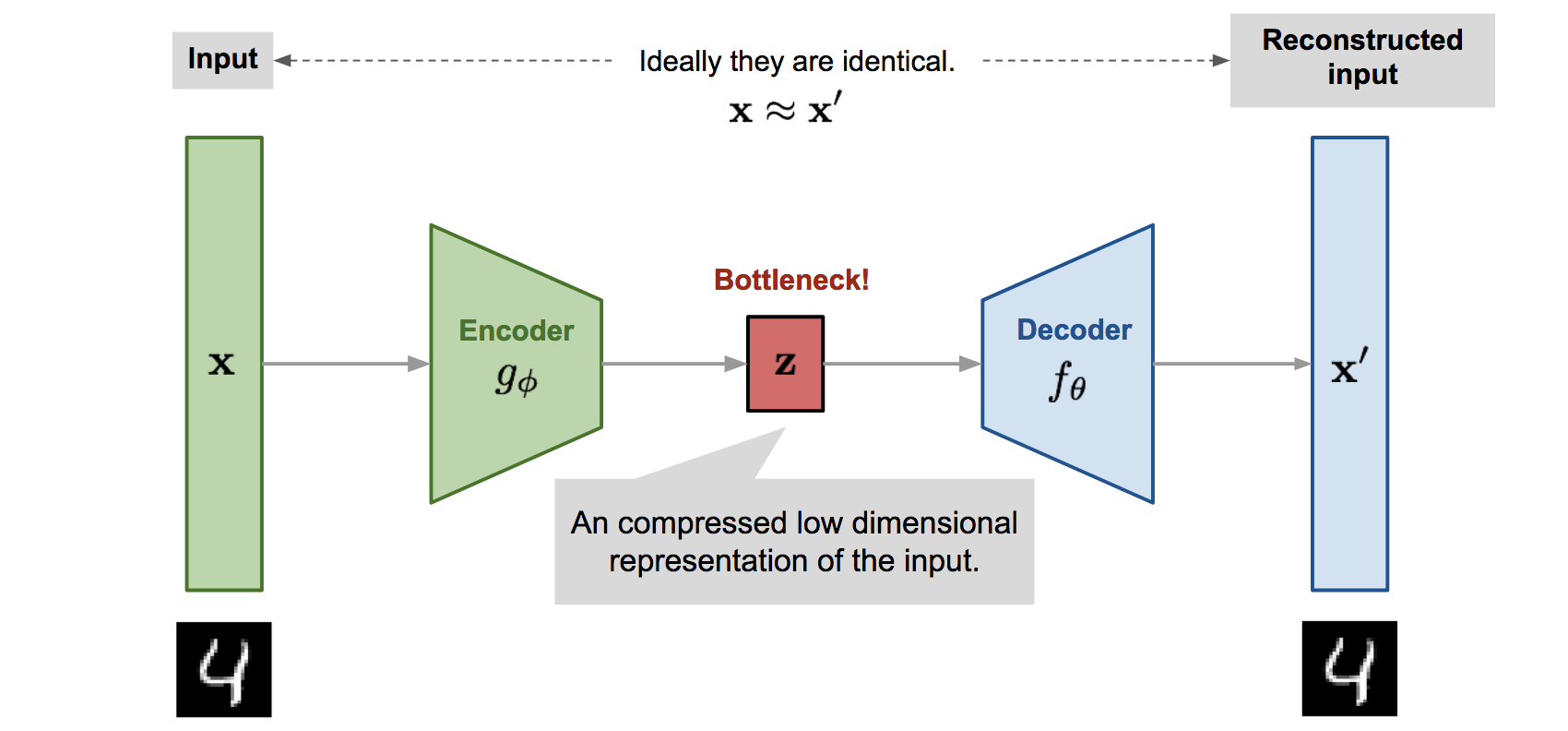

Autocoder is invented to reconstruct high-dimensional data using a neural network model with a narrow bottleneck layer in the middle (oops, this is probably not true for Variational Autoencoder, and we will investigate it in details in later sections). A nice byproduct is dimension reduction: the bottleneck layer captures a compressed latent encoding. Such a low-dimensional representation can be used as en embedding vector in various applications (i.e. search), help data compression, or reveal the underlying data generative factors.

Notation

| Symbol | Mean |

|---|---|

| $\mathcal{D}$ | The dataset, $\mathcal{D} = \{ \mathbf{x}^{(1)}, \mathbf{x}^{(2)}, \dots, \mathbf{x}^{(n)} \}$, contains $n$ data samples; $\vert\mathcal{D}\vert =n $. |

| $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ | Each data point is a vector of $d$ dimensions, $\mathbf{x}^{(i)} = [x^{(i)}_1, x^{(i)}_2, \dots, x^{(i)}_d]$. |

| $\mathbf{x}$ | One data sample from the dataset, $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{D}$. |

| $\mathbf{x}’$ | The reconstructed version of $\mathbf{x}$. |

| $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ | The corrupted version of $\mathbf{x}$. |

| $\mathbf{z}$ | The compressed code learned in the bottleneck layer. |

| $a_j^{(l)}$ | The activation function for the $j$-th neuron in the $l$-th hidden layer. |

| $g_{\phi}(.)$ | The encoding function parameterized by $\phi$. |

| $f_{\theta}(.)$ | The decoding function parameterized by $\theta$. |

| $q_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$ | Estimated posterior probability function, also known as probabilistic encoder. |

| $p_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}\vert\mathbf{z})$ | Likelihood of generating true data sample given the latent code, also known as probabilistic decoder. |

Autoencoder

Autoencoder is a neural network designed to learn an identity function in an unsupervised way to reconstruct the original input while compressing the data in the process so as to discover a more efficient and compressed representation. The idea was originated in the 1980s, and later promoted by the seminal paper by Hinton & Salakhutdinov, 2006.

It consists of two networks:

- Encoder network: It translates the original high-dimension input into the latent low-dimensional code. The input size is larger than the output size.

- Decoder network: The decoder network recovers the data from the code, likely with larger and larger output layers.

The encoder network essentially accomplishes the dimensionality reduction, just like how we would use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Matrix Factorization (MF) for. In addition, the autoencoder is explicitly optimized for the data reconstruction from the code. A good intermediate representation not only can capture latent variables, but also benefits a full decompression process.

The model contains an encoder function $g(.)$ parameterized by $\phi$ and a decoder function $f(.)$ parameterized by $\theta$. The low-dimensional code learned for input $\mathbf{x}$ in the bottleneck layer is $\mathbf{z} = g_\phi(\mathbf{x})$ and the reconstructed input is $\mathbf{x}’ = f_\theta(g_\phi(\mathbf{x}))$.

The parameters $(\theta, \phi)$ are learned together to output a reconstructed data sample same as the original input, $\mathbf{x} \approx f_\theta(g_\phi(\mathbf{x}))$, or in other words, to learn an identity function. There are various metrics to quantify the difference between two vectors, such as cross entropy when the activation function is sigmoid, or as simple as MSE loss:

Denoising Autoencoder

Since the autoencoder learns the identity function, we are facing the risk of “overfitting” when there are more network parameters than the number of data points.

To avoid overfitting and improve the robustness, Denoising Autoencoder (Vincent et al. 2008) proposed a modification to the basic autoencoder. The input is partially corrupted by adding noises to or masking some values of the input vector in a stochastic manner, $\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \sim \mathcal{M}_\mathcal{D}(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \vert \mathbf{x})$. Then the model is trained to recover the original input (note: not the corrupt one).

where $\mathcal{M}_\mathcal{D}$ defines the mapping from the true data samples to the noisy or corrupted ones.

This design is motivated by the fact that humans can easily recognize an object or a scene even the view is partially occluded or corrupted. To “repair” the partially destroyed input, the denoising autoencoder has to discover and capture relationship between dimensions of input in order to infer missing pieces.

For high dimensional input with high redundancy, like images, the model is likely to depend on evidence gathered from a combination of many input dimensions to recover the denoised version rather than to overfit one dimension. This builds up a good foundation for learning robust latent representation.

The noise is controlled by a stochastic mapping $\mathcal{M}_\mathcal{D}(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \vert \mathbf{x})$, and it is not specific to a particular type of corruption process (i.e. masking noise, Gaussian noise, salt-and-pepper noise, etc.). Naturally the corruption process can be equipped with prior knowledge

In the experiment of the original DAE paper, the noise is applied in this way: a fixed proportion of input dimensions are selected at random and their values are forced to 0. Sounds a lot like dropout, right? Well, the denoising autoencoder was proposed in 2008, 4 years before the dropout paper (Hinton, et al. 2012) ;)

Sparse Autoencoder

Sparse Autoencoder applies a “sparse” constraint on the hidden unit activation to avoid overfitting and improve robustness. It forces the model to only have a small number of hidden units being activated at the same time, or in other words, one hidden neuron should be inactivate most of time.

Recall that common activation functions include sigmoid, tanh, relu, leaky relu, etc. A neuron is activated when the value is close to 1 and inactivate with a value close to 0.

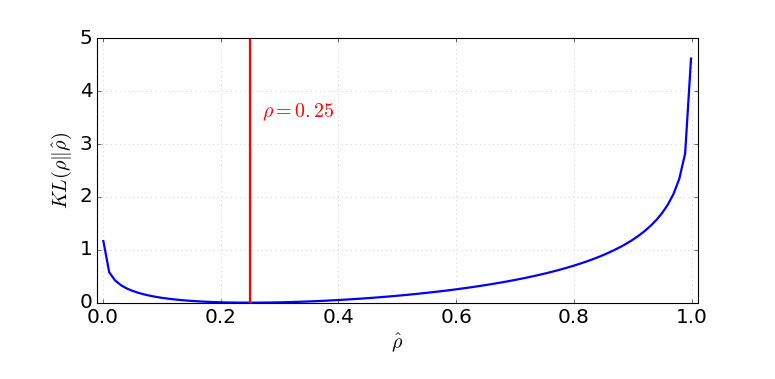

Let’s say there are $s_l$ neurons in the $l$-th hidden layer and the activation function for the $j$-th neuron in this layer is labelled as $a^{(l)}_j(.)$, $j=1, \dots, s_l$. The fraction of activation of this neuron $\hat{\rho}_j$ is expected to be a small number $\rho$, known as sparsity parameter; a common config is $\rho = 0.05$.

This constraint is achieved by adding a penalty term into the loss function. The KL-divergence $D_\text{KL}$ measures the difference between two Bernoulli distributions, one with mean $\rho$ and the other with mean $\hat{\rho}_j^{(l)}$. The hyperparameter $\beta$ controls how strong the penalty we want to apply on the sparsity loss.

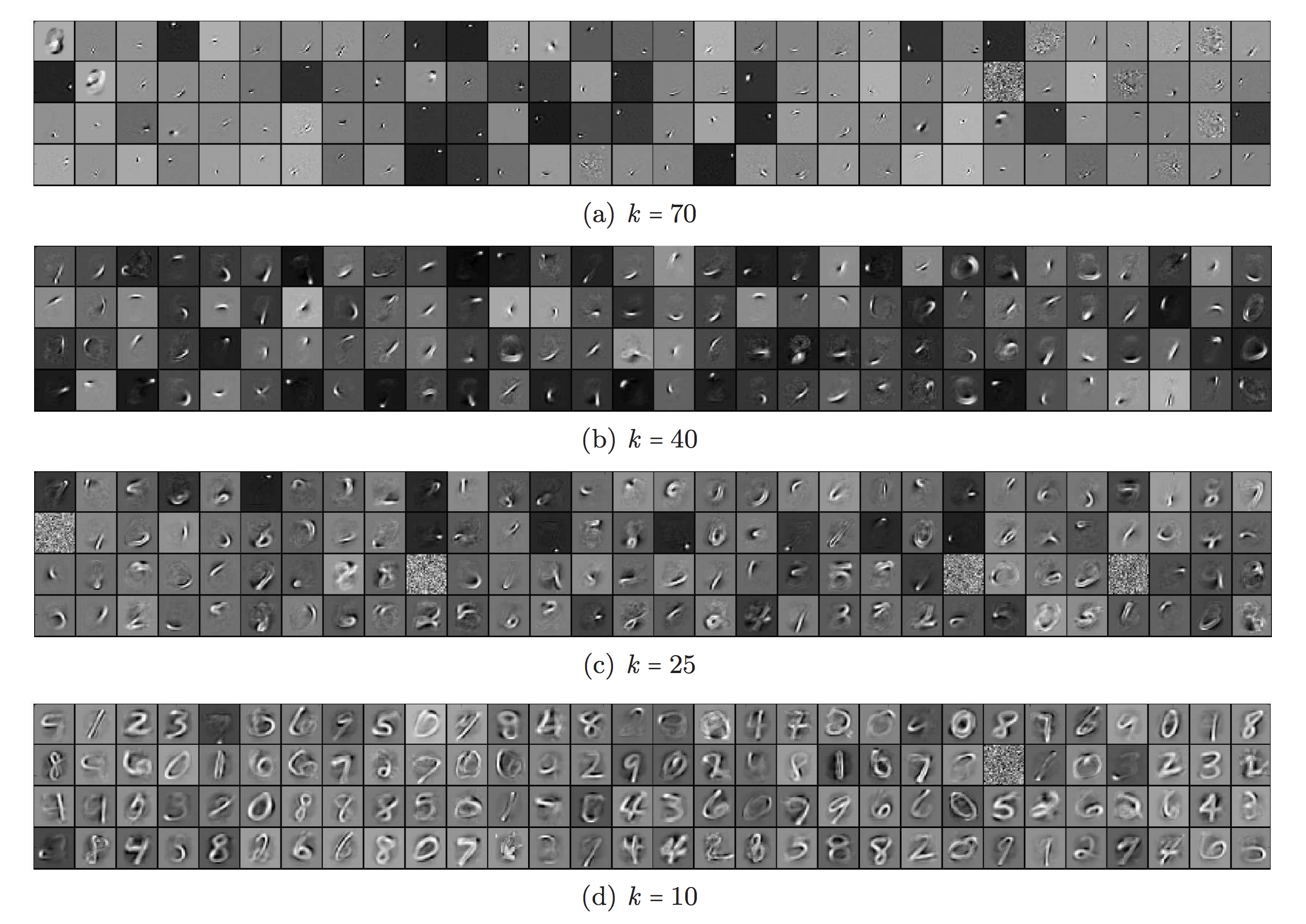

$k$-Sparse Autoencoder

In $k$-Sparse Autoencoder (Makhzani and Frey, 2013), the sparsity is enforced by only keeping the top k highest activations in the bottleneck layer with linear activation function. First we run feedforward through the encoder network to get the compressed code: $\mathbf{z} = g(\mathbf{x})$. Sort the values in the code vector $\mathbf{z}$. Only the k largest values are kept while other neurons are set to 0. This can be done in a ReLU layer with an adjustable threshold too. Now we have a sparsified code: $\mathbf{z}’ = \text{Sparsify}(\mathbf{z})$. Compute the output and the loss from the sparsified code, $L = |\mathbf{x} - f(\mathbf{z}’) |_2^2$. And, the back-propagation only goes through the top k activated hidden units!

Contractive Autoencoder

Similar to sparse autoencoder, Contractive Autoencoder (Rifai, et al, 2011) encourages the learned representation to stay in a contractive space for better robustness.

It adds a term in the loss function to penalize the representation being too sensitive to the input, and thus improve the robustness to small perturbations around the training data points. The sensitivity is measured by the Frobenius norm of the Jacobian matrix of the encoder activations with respect to the input:

where $h_j$ is one unit output in the compressed code $\mathbf{z} = f(x)$.

This penalty term is the sum of squares of all partial derivatives of the learned encoding with respect to input dimensions. The authors claimed that empirically this penalty was found to carve a representation that corresponds to a lower-dimensional non-linear manifold, while staying more invariant to majority directions orthogonal to the manifold.

VAE: Variational Autoencoder

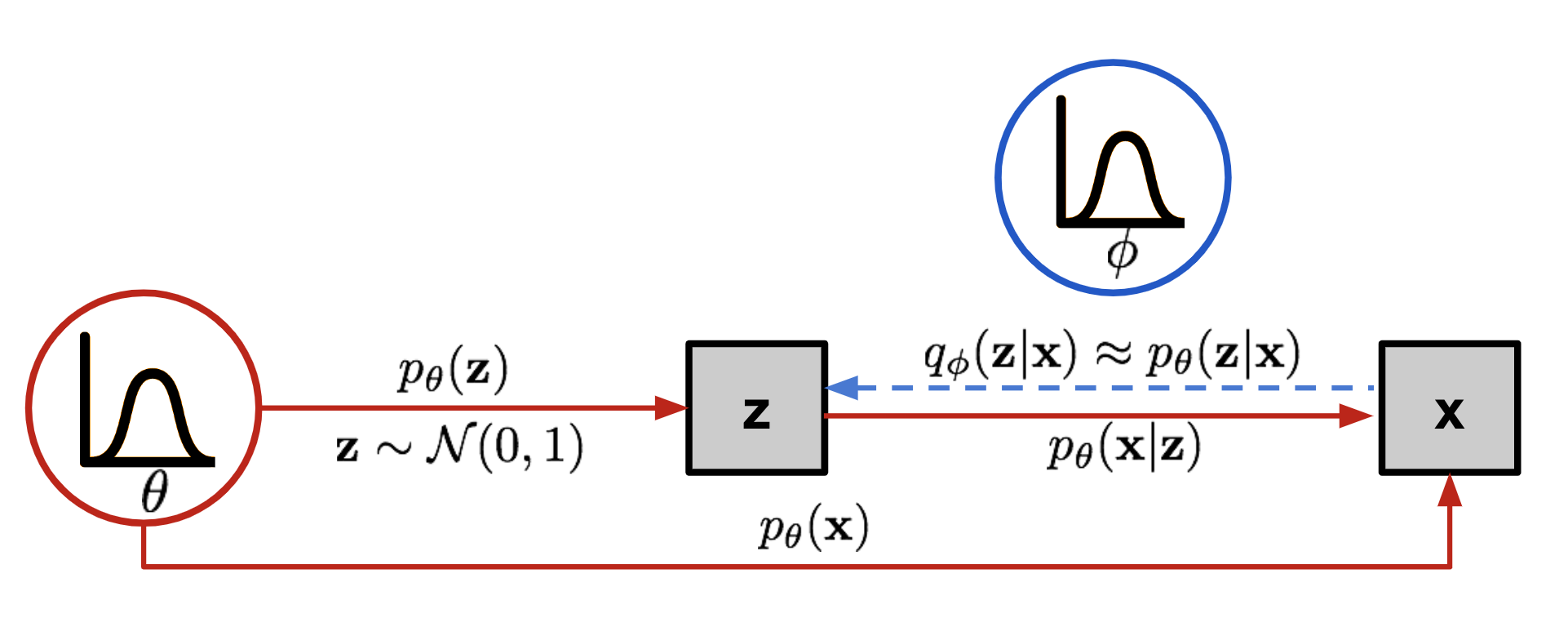

The idea of Variational Autoencoder (Kingma & Welling, 2014), short for VAE, is actually less similar to all the autoencoder models above, but deeply rooted in the methods of variational bayesian and graphical model.

Instead of mapping the input into a fixed vector, we want to map it into a distribution. Let’s label this distribution as $p_\theta$, parameterized by $\theta$. The relationship between the data input $\mathbf{x}$ and the latent encoding vector $\mathbf{z}$ can be fully defined by:

- Prior $p_\theta(\mathbf{z})$

- Likelihood $p_\theta(\mathbf{x}\vert\mathbf{z})$

- Posterior $p_\theta(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$

Assuming that we know the real parameter $\theta^{*}$ for this distribution. In order to generate a sample that looks like a real data point $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$, we follow these steps:

- First, sample a $\mathbf{z}^{(i)}$ from a prior distribution $p_{\theta^*}(\mathbf{z})$.

- Then a value $\mathbf{x}^{(i)}$ is generated from a conditional distribution $p_{\theta^*}(\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{z}^{(i)})$.

The optimal parameter $\theta^{*}$ is the one that maximizes the probability of generating real data samples:

Commonly we use the log probabilities to convert the product on RHS to a sum:

Now let’s update the equation to better demonstrate the data generation process so as to involve the encoding vector:

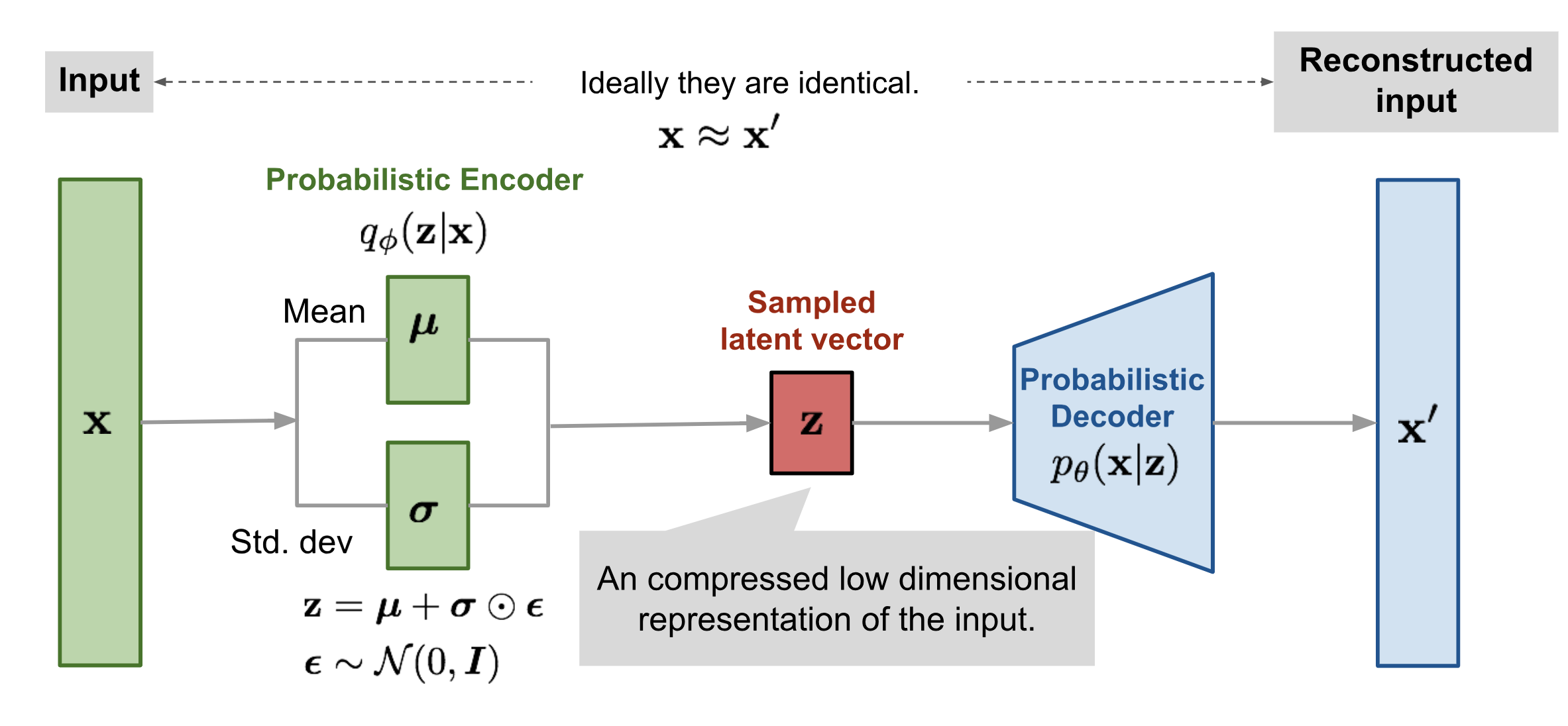

Unfortunately it is not easy to compute $p_\theta(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})$ in this way, as it is very expensive to check all the possible values of $\mathbf{z}$ and sum them up. To narrow down the value space to facilitate faster search, we would like to introduce a new approximation function to output what is a likely code given an input $\mathbf{x}$, $q_\phi(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$, parameterized by $\phi$.

Now the structure looks a lot like an autoencoder:

- The conditional probability $p_\theta(\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})$ defines a generative model, similar to the decoder $f_\theta(\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})$ introduced above. $p_\theta(\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})$ is also known as probabilistic decoder.

- The approximation function $q_\phi(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ is the probabilistic encoder, playing a similar role as $g_\phi(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ above.

Loss Function: ELBO

The estimated posterior $q_\phi(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$ should be very close to the real one $p_\theta(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$. We can use Kullback-Leibler divergence to quantify the distance between these two distributions. KL divergence $D_\text{KL}(X|Y)$ measures how much information is lost if the distribution Y is used to represent X.

In our case we want to minimize $D_\text{KL}( q_\phi(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x}) | p_\theta(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x}) )$ with respect to $\phi$.

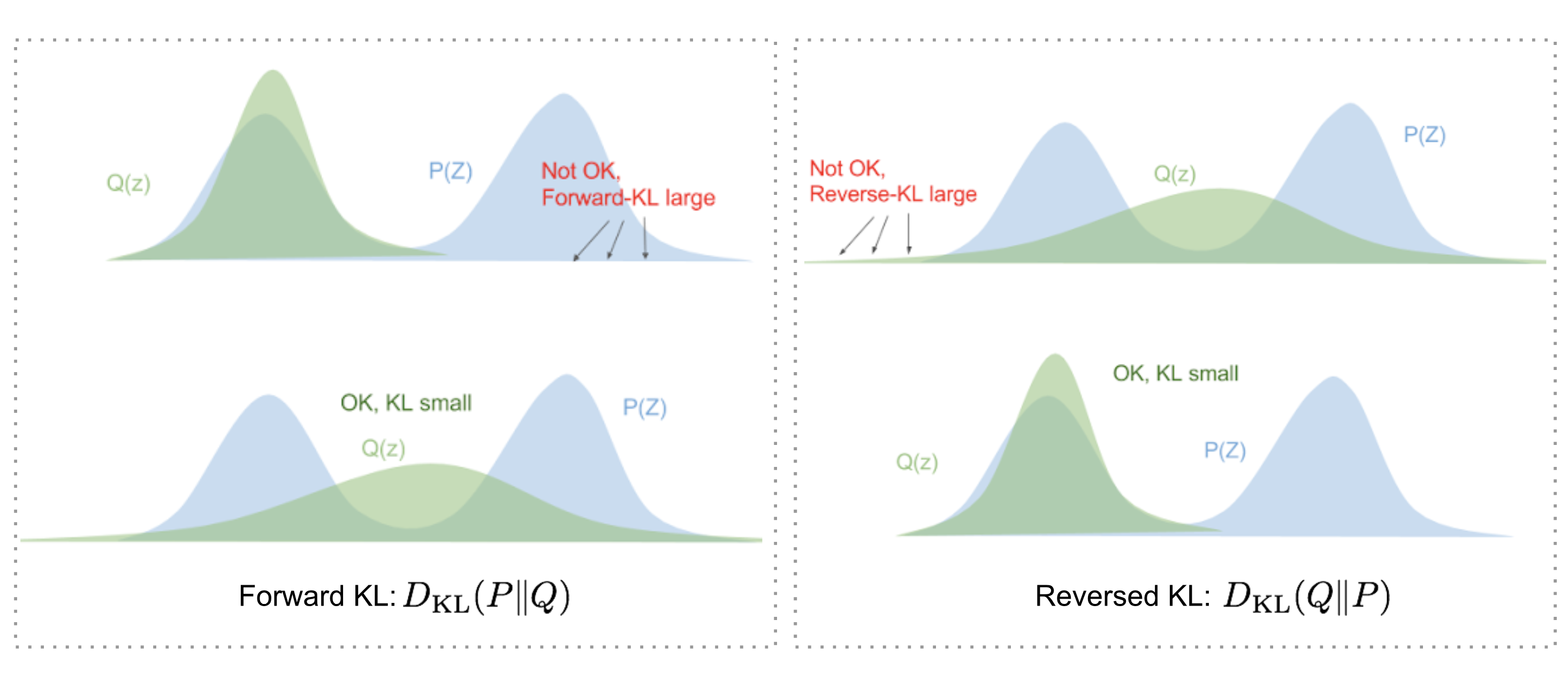

But why use $D_\text{KL}(q_\phi | p_\theta)$ (reversed KL) instead of $D_\text{KL}(p_\theta | q_\phi)$ (forward KL)? Eric Jang has a great explanation in his post on Bayesian Variational methods. As a quick recap:

- Forward KL divergence: $D_\text{KL}(P|Q) = \mathbb{E}_{z\sim P(z)} \log\frac{P(z)}{Q(z)}$; we have to ensure that Q(z)>0 wherever P(z)>0. The optimized variational distribution $q(z)$ has to cover over the entire $p(z)$.

- Reversed KL divergence: $D_\text{KL}(Q|P) = \mathbb{E}_{z\sim Q(z)} \log\frac{Q(z)}{P(z)}$; minimizing the reversed KL divergence squeezes the $Q(z)$ under $P(z)$.

Let’s now expand the equation:

So we have:

Once rearrange the left and right hand side of the equation,

The LHS of the equation is exactly what we want to maximize when learning the true distributions: we want to maximize the (log-)likelihood of generating real data (that is $\log p_\theta(\mathbf{x})$) and also minimize the difference between the real and estimated posterior distributions (the term $D_\text{KL}$ works like a regularizer). Note that $p_\theta(\mathbf{x})$ is fixed with respect to $q_\phi$.

The negation of the above defines our loss function:

In Variational Bayesian methods, this loss function is known as the variational lower bound, or evidence lower bound. The “lower bound” part in the name comes from the fact that KL divergence is always non-negative and thus $-L_\text{VAE}$ is the lower bound of $\log p_\theta (\mathbf{x})$.

Therefore by minimizing the loss, we are maximizing the lower bound of the probability of generating real data samples.

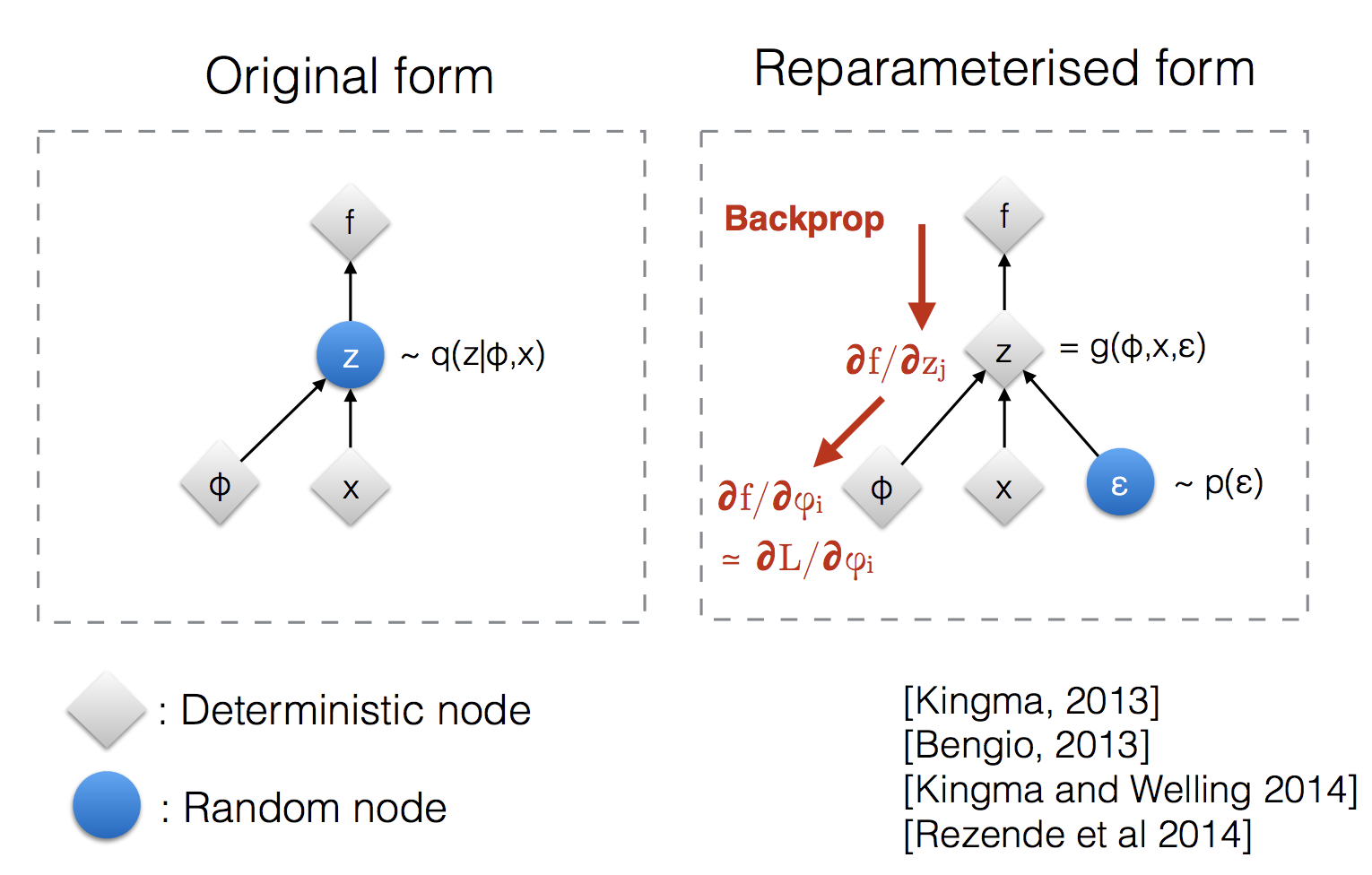

Reparameterization Trick

The expectation term in the loss function invokes generating samples from $\mathbf{z} \sim q_\phi(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$. Sampling is a stochastic process and therefore we cannot backpropagate the gradient. To make it trainable, the reparameterization trick is introduced: It is often possible to express the random variable $\mathbf{z}$ as a deterministic variable $\mathbf{z} = \mathcal{T}_\phi(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\epsilon})$, where $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}$ is an auxiliary independent random variable, and the transformation function $\mathcal{T}_\phi$ parameterized by $\phi$ converts $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}$ to $\mathbf{z}$.

For example, a common choice of the form of $q_\phi(\mathbf{z}\vert\mathbf{x})$ is a multivariate Gaussian with a diagonal covariance structure:

where $\odot$ refers to element-wise product.

The reparameterization trick works for other types of distributions too, not only Gaussian. In the multivariate Gaussian case, we make the model trainable by learning the mean and variance of the distribution, $\mu$ and $\sigma$, explicitly using the reparameterization trick, while the stochasticity remains in the random variable $\boldsymbol{\epsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \boldsymbol{I})$.

Beta-VAE

If each variable in the inferred latent representation $\mathbf{z}$ is only sensitive to one single generative factor and relatively invariant to other factors, we will say this representation is disentangled or factorized. One benefit that often comes with disentangled representation is good interpretability and easy generalization to a variety of tasks.

For example, a model trained on photos of human faces might capture the gentle, skin color, hair color, hair length, emotion, whether wearing a pair of glasses and many other relatively independent factors in separate dimensions. Such a disentangled representation is very beneficial to facial image generation.

β-VAE (Higgins et al., 2017) is a modification of Variational Autoencoder with a special emphasis to discover disentangled latent factors. Following the same incentive in VAE, we want to maximize the probability of generating real data, while keeping the distance between the real and estimated posterior distributions small (say, under a small constant $\delta$):

We can rewrite it as a Lagrangian with a Lagrangian multiplier $\beta$ under the KKT condition. The above optimization problem with only one inequality constraint is equivalent to maximizing the following equation $\mathcal{F}(\theta, \phi, \beta)$:

The loss function of $\beta$-VAE is defined as:

where the Lagrangian multiplier $\beta$ is considered as a hyperparameter.

Since the negation of $L_\text{BETA}(\phi, \beta)$ is the lower bound of the Lagrangian $\mathcal{F}(\theta, \phi, \beta)$. Minimizing the loss is equivalent to maximizing the Lagrangian and thus works for our initial optimization problem.

When $\beta=1$, it is same as VAE. When $\beta > 1$, it applies a stronger constraint on the latent bottleneck and limits the representation capacity of $\mathbf{z}$. For some conditionally independent generative factors, keeping them disentangled is the most efficient representation. Therefore a higher $\beta$ encourages more efficient latent encoding and further encourages the disentanglement. Meanwhile, a higher $\beta$ may create a trade-off between reconstruction quality and the extent of disentanglement.

Burgess, et al. (2017) discussed the distentangling in $\beta$-VAE in depth with an inspiration by the information bottleneck theory and further proposed a modification to $\beta$-VAE to better control the encoding representation capacity.

VQ-VAE and VQ-VAE-2

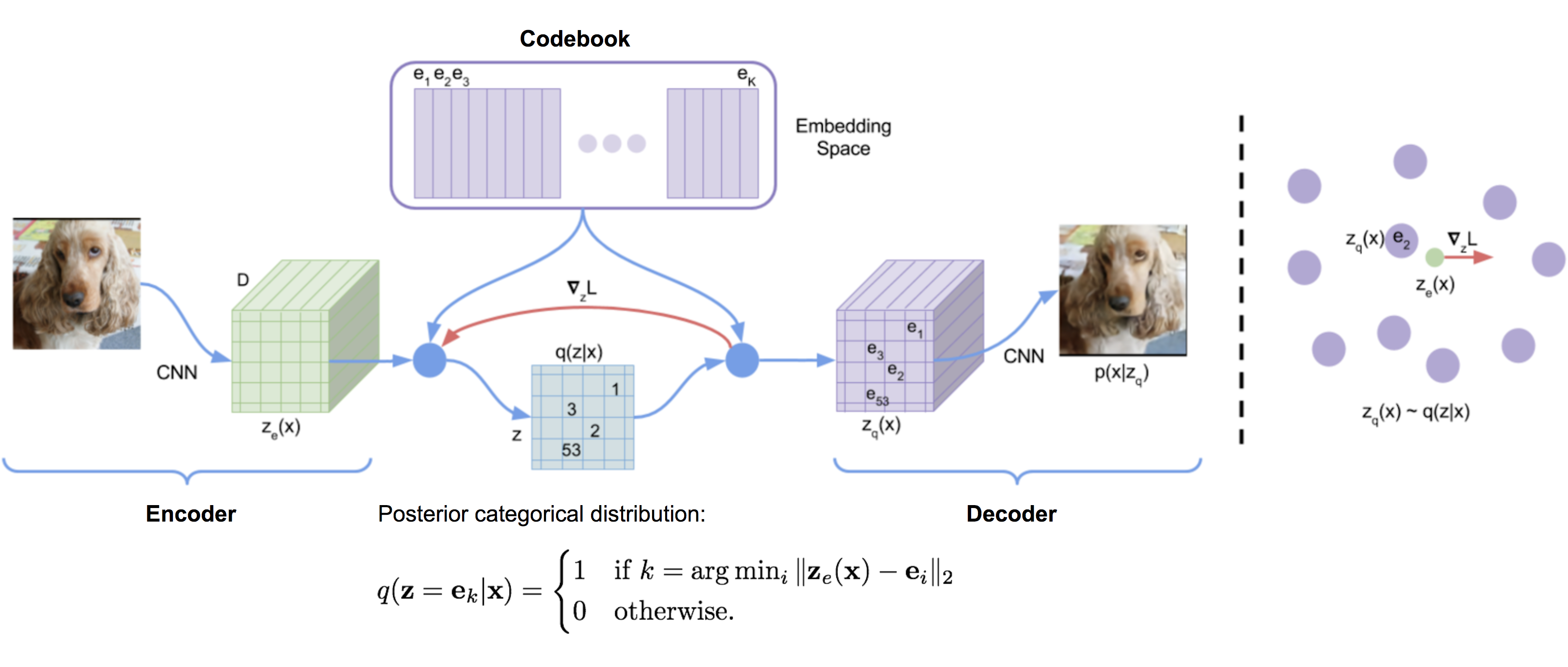

The VQ-VAE (“Vector Quantised-Variational AutoEncoder”; van den Oord, et al. 2017) model learns a discrete latent variable by the encoder, since discrete representations may be a more natural fit for problems like language, speech, reasoning, etc.

Vector quantisation (VQ) is a method to map $K$-dimensional vectors into a finite set of “code” vectors. The process is very much similar to KNN algorithm. The optimal centroid code vector that a sample should be mapped to is the one with minimum euclidean distance.

Let $\mathbf{e} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times D}, i=1, \dots, K$ be the latent embedding space (also known as “codebook”) in VQ-VAE, where $K$ is the number of latent variable categories and $D$ is the embedding size. An individual embedding vector is $\mathbf{e}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{D}, i=1, \dots, K$.

The encoder output $E(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{z}_e$ goes through a nearest-neighbor lookup to match to one of $K$ embedding vectors and then this matched code vector becomes the input for the decoder $D(.)$:

Note that the discrete latent variables can have different shapes in differnet applications; for example, 1D for speech, 2D for image and 3D for video.

Because argmin() is non-differentiable on a discrete space, the gradients $\nabla_z L$ from decoder input $\mathbf{z}_q$ is copied to the encoder output $\mathbf{z}_e$. Other than reconstruction loss, VQ-VAE also optimizes:

- VQ loss: The L2 error between the embedding space and the encoder outputs.

- Commitment loss: A measure to encourage the encoder output to stay close to the embedding space and to prevent it from fluctuating too frequently from one code vector to another.

where $\text{sg}[.]$ is the stop_gradient operator.

The embedding vectors in the codebook is updated through EMA (exponential moving average). Given a code vector $\mathbf{e}_i$, say we have $n_i$ encoder output vectors, $\{\mathbf{z}_{i,j}\}_{j=1}^{n_i}$, that are quantized to $\mathbf{e}_i$:

where $(t)$ refers to batch sequence in time. $N_i$ and $\mathbf{m}_i$ are accumulated vector count and volume, respectively.

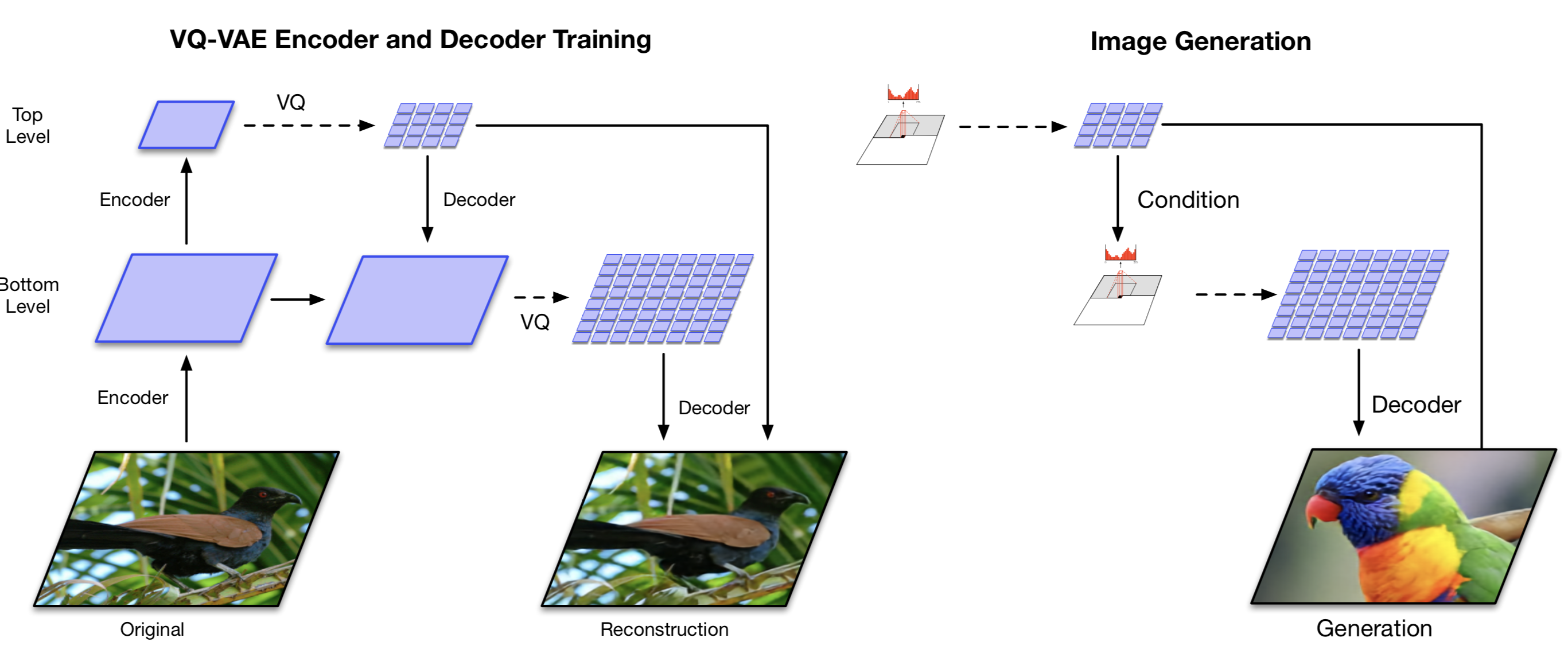

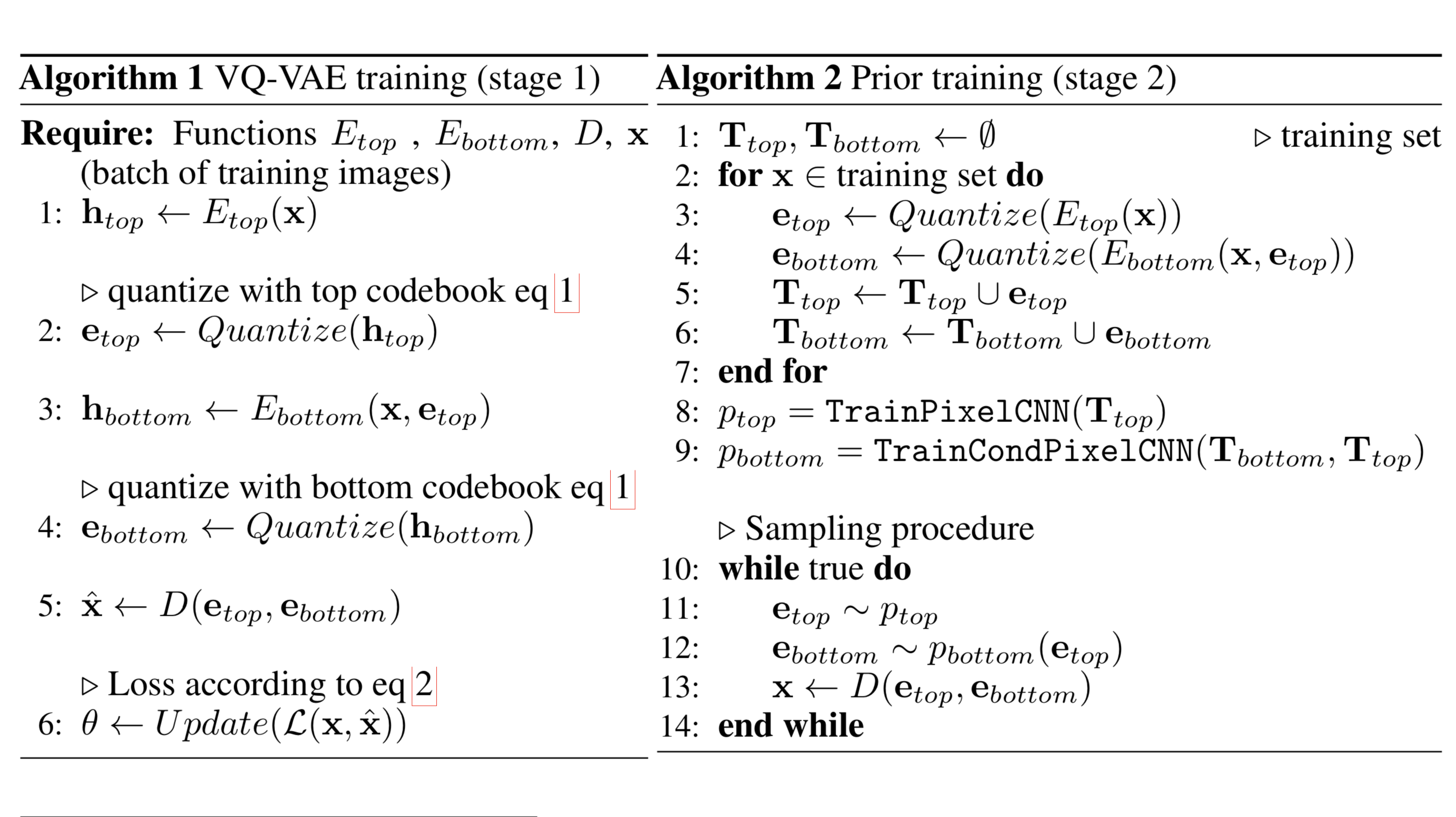

VQ-VAE-2 (Ali Razavi, et al. 2019) is a two-level hierarchical VQ-VAE combined with self-attention autoregressive model.

- Stage 1 is to train a hierarchical VQ-VAE: The design of hierarchical latent variables intends to separate local patterns (i.e., texture) from global information (i.e., object shapes). The training of the larger bottom level codebook is conditioned on the smaller top level code too, so that it does not have to learn everything from scratch.

- Stage 2 is to learn a prior over the latent discrete codebook so that we sample from it and generate images. In this way, the decoder can receive input vectors sampled from a similar distribution as the one in training. A powerful autoregressive model enhanced with multi-headed self-attention layers is used to capture the prior distribution (like PixelSNAIL; Chen et al 2017).

Considering that VQ-VAE-2 depends on discrete latent variables configured in a simple hierarchical setting, the quality of its generated images are pretty amazing.

TD-VAE

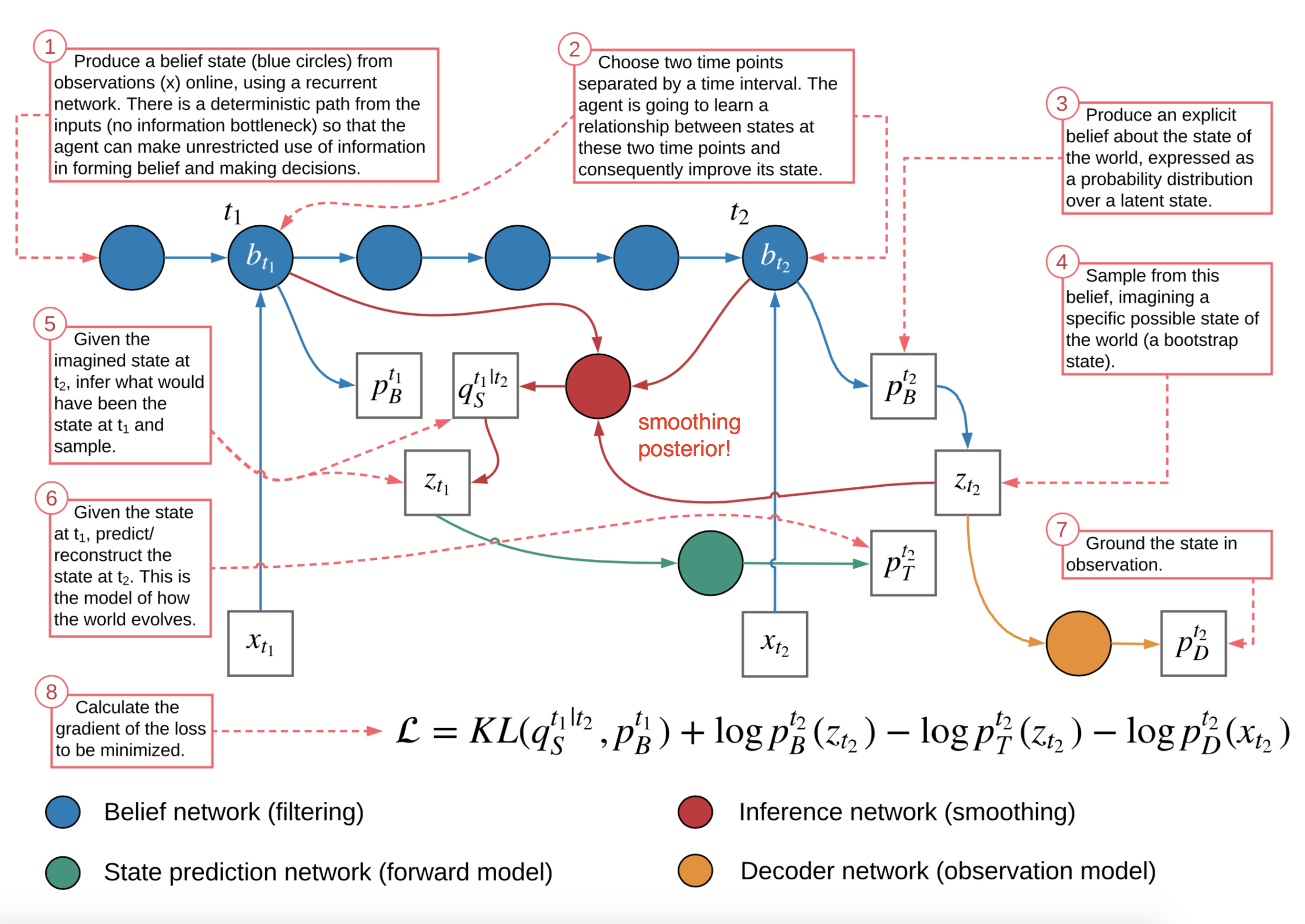

TD-VAE (“Temporal Difference VAE”; Gregor et al., 2019) works with sequential data. It relies on three main ideas, described below.

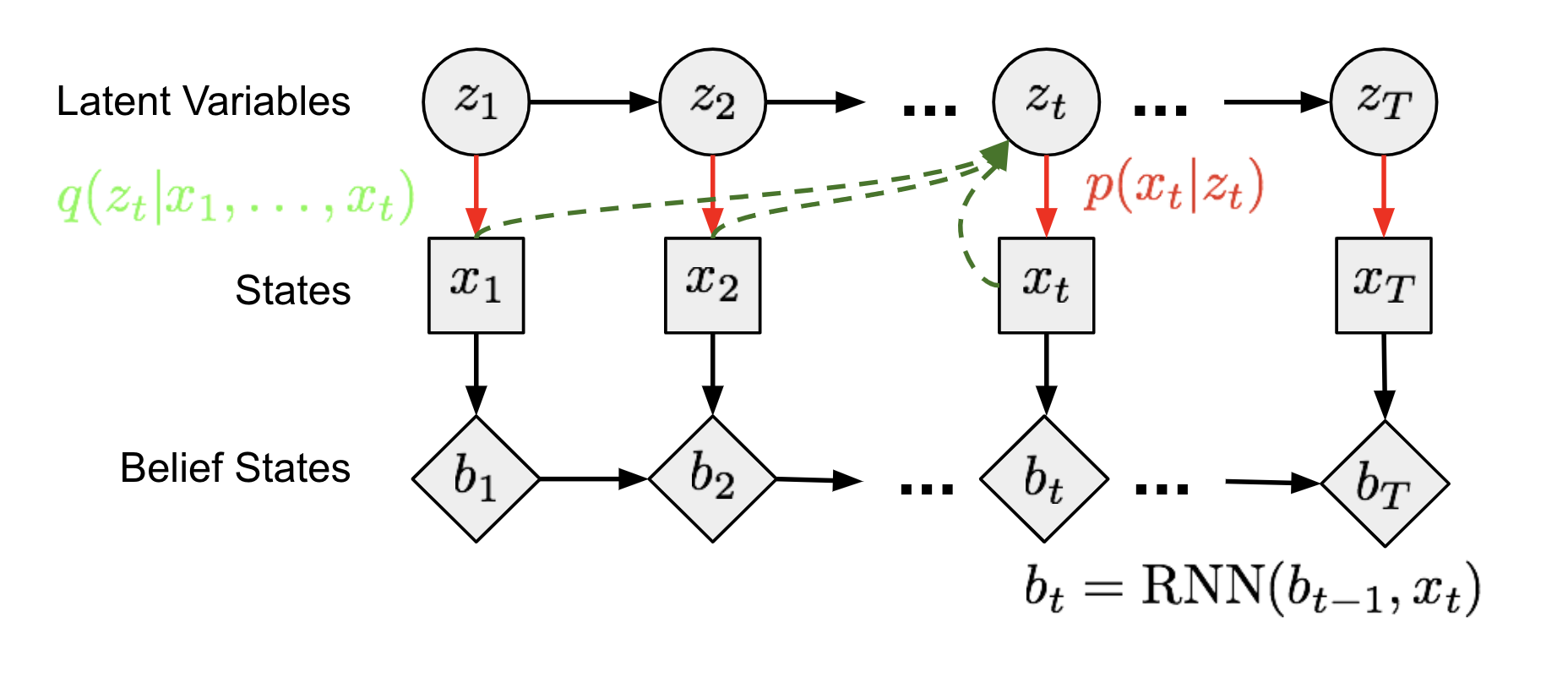

1. State-Space Models

In (latent) state-space models, a sequence of unobserved hidden states $\mathbf{z} = (z_1, \dots, z_T)$ determine the observation states $\mathbf{x} = (x_1, \dots, x_T)$. Each time step in the Markov chain model in Fig. 13 can be trained in a similar manner as in Fig. 6, where the intractable posterior $p(z \vert x)$ is approximated by a function $q(z \vert x)$.

2. Belief State

An agent should learn to encode all the past states to reason about the future, named as belief state, $b_t = belief(x_1, \dots, x_t) = belief(b_{t-1}, x_t)$. Given this, the distribution of future states conditioned on the past can be written as $p(x_{t+1}, \dots, x_T \vert x_1, \dots, x_t) \approx p(x_{t+1}, \dots, x_T \vert b_t)$. The hidden states in a recurrent policy are used as the agent’s belief state in TD-VAE. Thus we have $b_t = \text{RNN}(b_{t-1}, x_t)$.

3. Jumpy Prediction

Further, an agent is expected to imagine distant futures based on all the information gathered so far, suggesting the capability of making jumpy predictions, that is, predicting states several steps further into the future.

Recall what we have learned from the variance lower bound above:

Now let’s model the distribution of the state $x_t$ as a probability function conditioned on all the past states $x_{<t}$ and two latent variables, $z_t$ and $z_{t-1}$, at current time step and one step back:

Continue expanding the equation:

Notice two things:

- The red terms can be ignored according to Markov assumptions.

- The blue term is expanded according to Markov assumptions.

- The green term is expanded to include an one-step prediction back to the past as a smoothing distribution.

Precisely, there are four types of distributions to learn:

- $p_D(.)$ is the decoder distribution:

- $p(x_t \mid z_t)$ is the encoder by the common definition;

- $p(x_t \mid z_t) \to p_D(x_t \mid z_t)$;

- $p_T(.)$ is the transition distribution:

- $p(z_t \mid z_{t-1})$ captures the sequential dependency between latent variables;

- $p(z_t \mid z_{t-1}) \to p_T(z_t \mid z_{t-1})$;

- $p_B(.)$ is the belief distribution:

- Both $p(z_{t-1} \mid x_{<t})$ and $q(z_t \mid x_{\leq t})$ can use the belief states to predict the latent variables;

- $p(z_{t-1} \mid x_{<t}) \to p_B(z_{t-1} \mid b_{t-1})$;

- $q(z_{t} \mid x_{\leq t}) \to p_B(z_t \mid b_t)$;

- $p_S(.)$ is the smoothing distribution:

- The back-to-past smoothing term $q(z_{t-1} \mid z_t, x_{\leq t})$ can be rewritten to be dependent of belief states too;

- $q(z_{t-1} \mid z_t, x_{\leq t}) \to p_S(z_{t-1} \mid z_t, b_{t-1}, b_t)$;

To incorporate the idea of jumpy prediction, the sequential ELBO has to not only work on $t, t+1$, but also two distant timestamp $t_1 < t_2$. Here is the final TD-VAE objective function to maximize:

Cited as:

@article{weng2018VAE,

title = "From Autoencoder to Beta-VAE",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2018",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2018-08-12-vae/"

}

References

[1] Geoffrey E. Hinton, and Ruslan R. Salakhutdinov. “Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks.” Science 313.5786 (2006): 504-507.

[2] Pascal Vincent, et al. “Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders.” ICML, 2008.

[3] Pascal Vincent, et al. “Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion.”. Journal of machine learning research 11.Dec (2010): 3371-3408.

[4] Geoffrey E. Hinton, Nitish Srivastava, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan R. Salakhutdinov. “Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1207.0580 (2012).

[5] Sparse Autoencoder by Andrew Ng.

[6] Alireza Makhzani, Brendan Frey (2013). “k-sparse autoencoder”. ICLR 2014.

[7] Salah Rifai, et al. “Contractive auto-encoders: Explicit invariance during feature extraction.” ICML, 2011.

[8] Diederik P. Kingma, and Max Welling. “Auto-encoding variational bayes.” ICLR 2014.

[9] Tutorial - What is a variational autoencoder? on jaan.io

[10] Youtube tutorial: Variational Autoencoders by Arxiv Insights

[11] “A Beginner’s Guide to Variational Methods: Mean-Field Approximation” by Eric Jang.

[12] Carl Doersch. “Tutorial on variational autoencoders.” arXiv:1606.05908, 2016.

[13] Irina Higgins, et al. "$\beta$-VAE: Learning basic visual concepts with a constrained variational framework." ICLR 2017.

[14] Christopher P. Burgess, et al. “Understanding disentangling in beta-VAE.” NIPS 2017.

[15] Aaron van den Oord, et al. “Neural Discrete Representation Learning” NIPS 2017.

[16] Ali Razavi, et al. “Generating Diverse High-Fidelity Images with VQ-VAE-2”. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00446 (2019).

[17] Xi Chen, et al. “PixelSNAIL: An Improved Autoregressive Generative Model.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.09763 (2017).

[18] Karol Gregor, et al. “Temporal Difference Variational Auto-Encoder.” ICLR 2019.