Large pretrained language models are trained over a sizable collection of online data. They unavoidably acquire certain toxic behavior and biases from the Internet. Pretrained language models are very powerful and have shown great success in many NLP tasks. However, to safely deploy them for practical real-world applications demands a strong safety control over the model generation process.

Many challenges are associated with the effort to diminish various types of unsafe content:

- First, there are a variety of unsafe content types, such as toxicity, abusiveness, hate speech, biases, stereotypes, cyberbullying, identity attacks and more, which may or may not demand different treatment.

- Second, there is no clearly and widely agreed-upon categorization and definition of unsafe behavior in pretrained language models. Individual perceptions could vary a lot due to different social backgrounds.

In this post, we delve into the issue of toxicity in language models. As I’m still struggling to find a concrete definition of toxic content, I list a couple in the literature below.

[Perspective API] A rude, disrespectful, or unreasonable comment; likely to make people leave a discussion.

[Kurita et al. 2019] Content that can offend or harm its recipients, including hate speech, racism, and offensive language.

[Pavlopoulos et al. 2020] We use the term ’toxic’ as an umbrella term, but we note that the literature uses several terms for different kinds of toxic language or related phenomena: ‘offensive’, ‘abusive’, ‘hateful’, etc.

Overall, toxicity is a broad term to describe several types of unsafe content. Methodologies in this post can be applied given some form of definition of toxicity; e.g. presented in the instruction for annotators. How to properly define the concept of toxicity and thus collect accurate annotation labels is out of the scope of this post.

Categorization of Toxic Content

How to categorize toxic content is not a straightforward task. Which content should be considered toxic and what types of toxic content exist can be very subjective. Language that does not look offensive to one group might seem inappropriate to another.

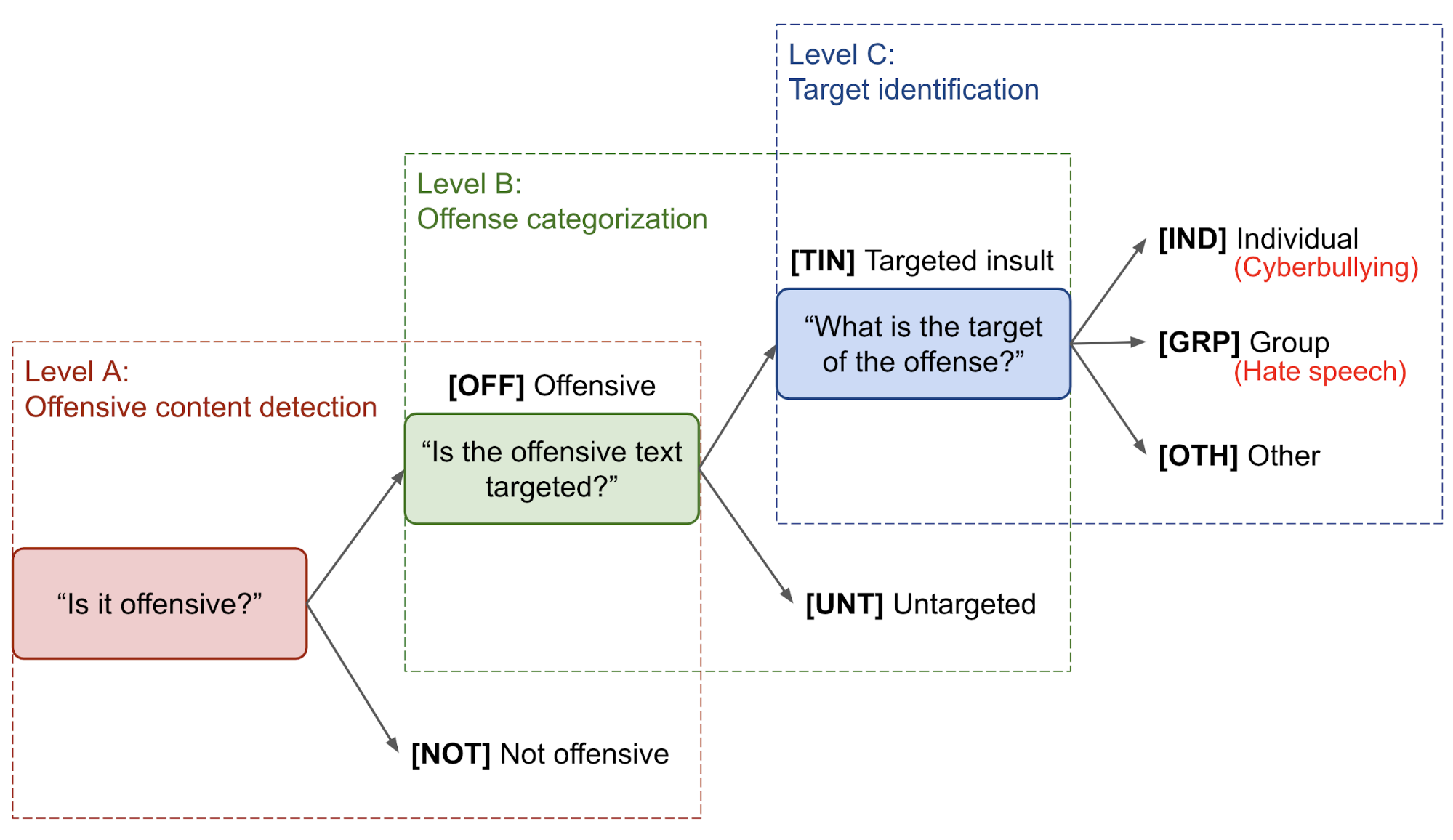

One popular categorization of offensive language is proposed by Zampieri et al. (2019), a three-level hierarchical taxonomy considering both the type and the target of offense. The Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID) dataset is collected based on this taxonomy.

- Level A: “Is it offensive?”

[OFF]Offensive: Inappropriate language, insults, or threats.[NOT]Not offensive: No offense or profanity.

- Level B: “Is the offensive text targeted?”

[TIN]Targeted Insult: Targeted insult or threat towards an individual, a group or other.[UNT]Untargeted: Non-targeted profanity and swearing.

- Level C: What is the target?

[IND]The offense targets an individual, often defined as “cyberbullying”.[GRP]The offense targets a group of people based on ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or other common characteristic, often defined as “hate speech”.[OTH]The target can belong to other categories, such as an organization, an event, an issue, etc.

Data Collection

Preparing a dataset of samples labelled as “safe” vs “unsafe” is the foundation for training a toxic language classifier and further providing signals for model detoxification.

Human Annotations

Vidgen & Derczynski (2020) summarized that training data annotations for toxicity detection on the high level can be collected by:

- Expert coding: An expert has enough knowledge or training to complete the annotation tasks with good quality, such as a researcher who studies prejudice, a student with moderate level of training, or a NLP practitioner. It is more expensive but produces high-quality data.

- Crowdsourcing: Crowdsourcing platform pairs a large number of non-expert annotators with tasks. It is easier to scale up but demands more attention on quality control.

- Professional moderators: Professional moderators are experienced, well-trained on the tasks, but their goals are likely to optimize for the output specific to the platform.

- Synthetic data: Training dataset can also be manually created by relevant content creators to cover a broad range of toxic content types.

Crowdsourcing is the most common approach among them (Davidson et al. 2017, Zampieri et al. 2019) and there are several good practices to improve the data quality:

- Test data: A small set of annotations collected from a few experts can be used as test questions (Zampieri et al. 2019) to filter out human annotators on the crowdsourcing platform who cannot achieve a certain threshold.

- Clear guidelines: Detailed instructions are useful to guide annotators to produce aligned and consistent labels. Without any guideline, annotators are encouraged to apply their personal perceptions, which could be problematic because (1) subjective interpretation of toxic content varies across individuals greatly and (2) it is tricky to mark certain types of noise like sarcasm and irony without any guideline.

- Majority vote: It is very common that we need labels from multiple annotators per sample and take the majority vote.

- Understanding annotators’ identities: Demographic background has a big impact on the annotator’s understanding of the task. We should aim to recruit diverse and qualified annotators.

Semi-supervised Dataset

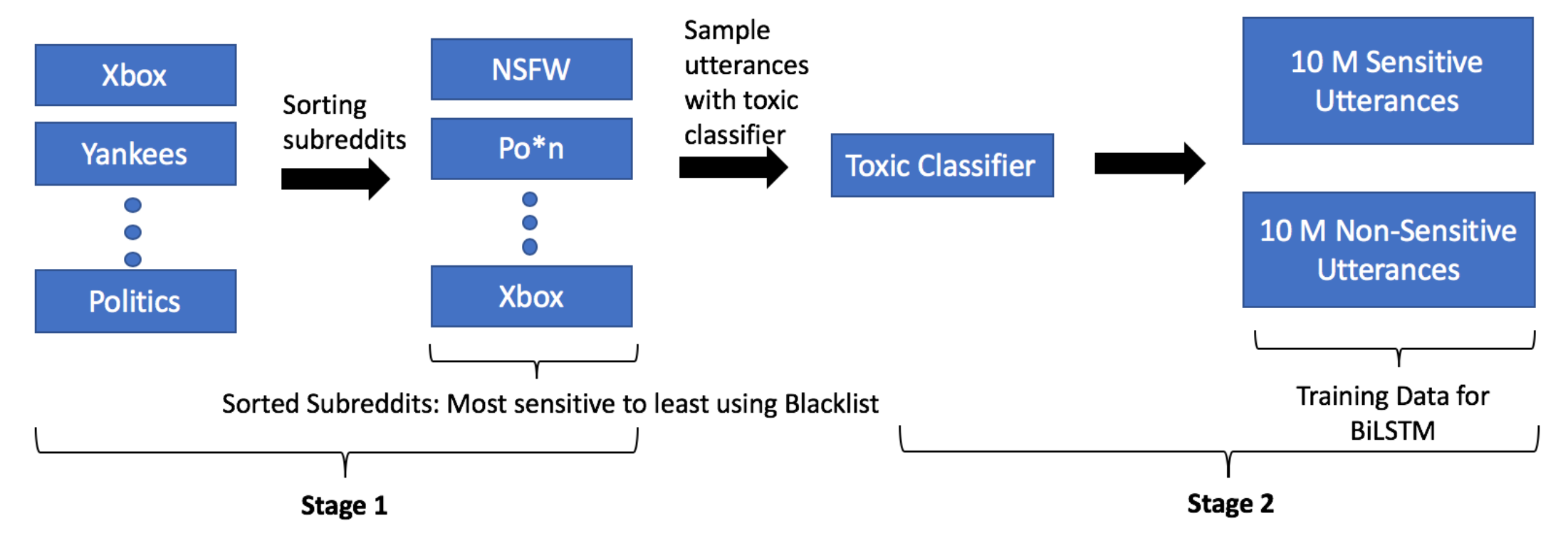

Khatri et al. (2018) proposed a simple approach to bootstrap a large amount of semi-supervised dataset for learning toxic content classifiers. Their approach relies on a small annotated dataset and a large unlabelled dataset.

- First, they gather a blacklist of 800+ words covering topics of profanity, hate, sexual content and insults. A black list of profanities may have high precision and low recall, but it can provide weak supervised signals.

- Subreddits are sorted by the percentage of blacklisted words. Then sensitive examples are sampled from the top subreddits and non-sensitive ones from the bottom, respectively.

- Train a weak binary classifier to further select more samples from the sorted subreddits,

- Sensitive: contain blacklisted words or toxic classifier confidence > 0.8;

- Non-sensitive: not contain blacklisted words and toxic classifier confidence < 0.3

- Given this large expanded dataset, train a new classifier named “Two-stage bootstrap” (TS bootstrap).

Their experiments showed that the TS bootstrap classifier achieved pretty good numbers on F1 score, accuracy and recall and it could also transfer to out-of-domain test data.

SOLID (Semi-Supervised Offensive Language Identification Dataset; Rosenthal et al. 2020) contains 9+ M tweets annotated with the same taxonomy system as for OLID. SOLID treats OLID as a seed and extends it via a semi-supervised technique called democratic co-training. Democratic co-training (Zhou & Goldman, 2004) creates a large dataset from noisy labels provided by a collection of diverse models trained on a small supervised dataset. SOLID is constructed by:

- First, train a diverse set of supervised models on the labeled dataset OLID. The paper experimented with PMI (n-gram-based similarity), FastText (shallow neural model similar to BoW model), LSTM and BERT.

- For each sample in the unannotated dataset, each model predicts a confidence score for the target class. The scores are aggregated by taking

avg()ormin(). Samples with high confidence are added into the dataset.

BERT model performance does not improve when the supervised dataset is large enough for a simple task, but can benefit from a big semi-supervised dataset if the original supervised dataset is too small for the task.

Toxicity Detection

Given a supervised dataset, we can train a text classifier from scratch or fine-tune a pretrained language model to perform the classification task. But what if training samples are not good or sufficient enough? What if we don’t have access to such a supervised dataset?

Adversarial Attacks

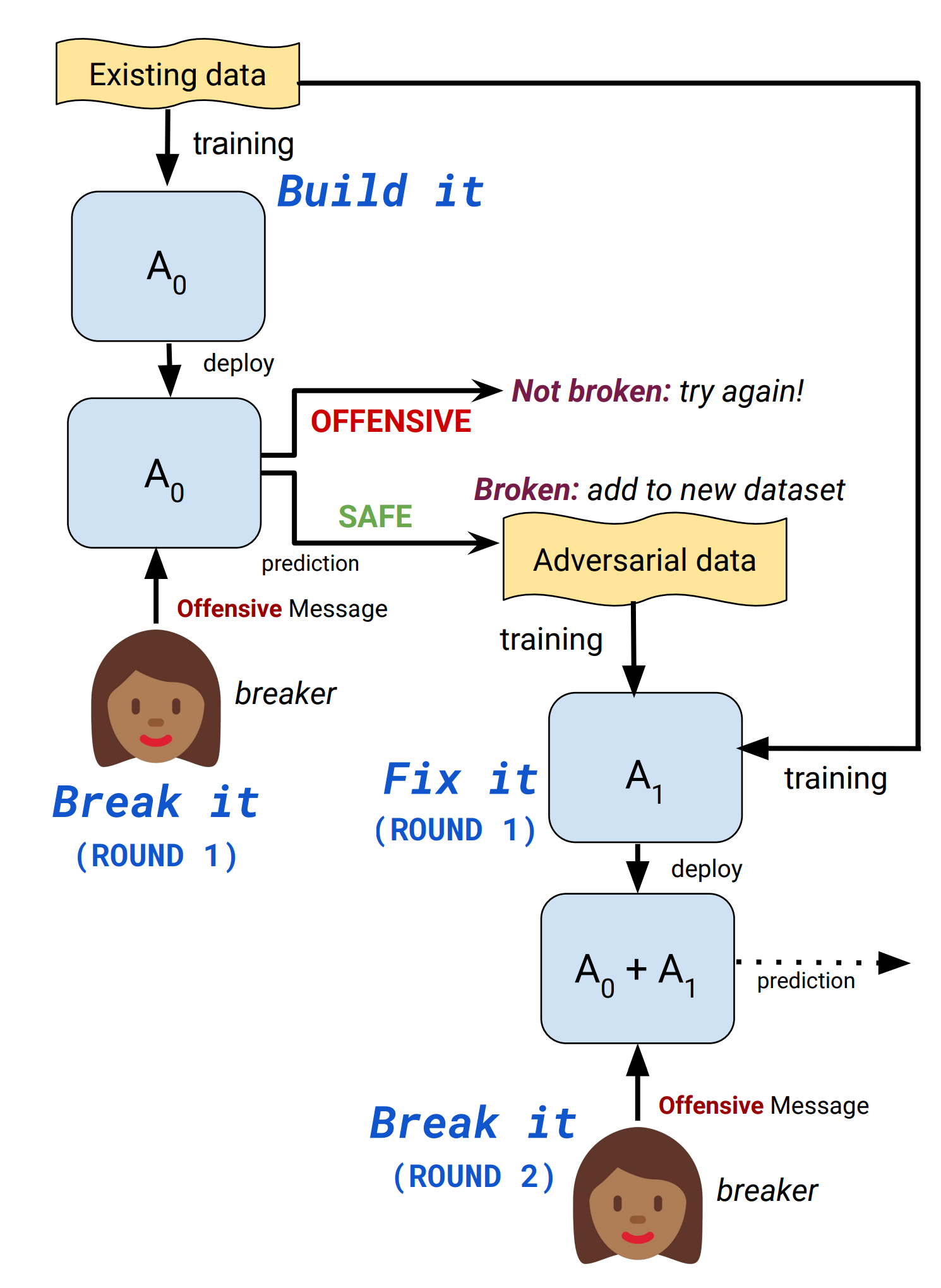

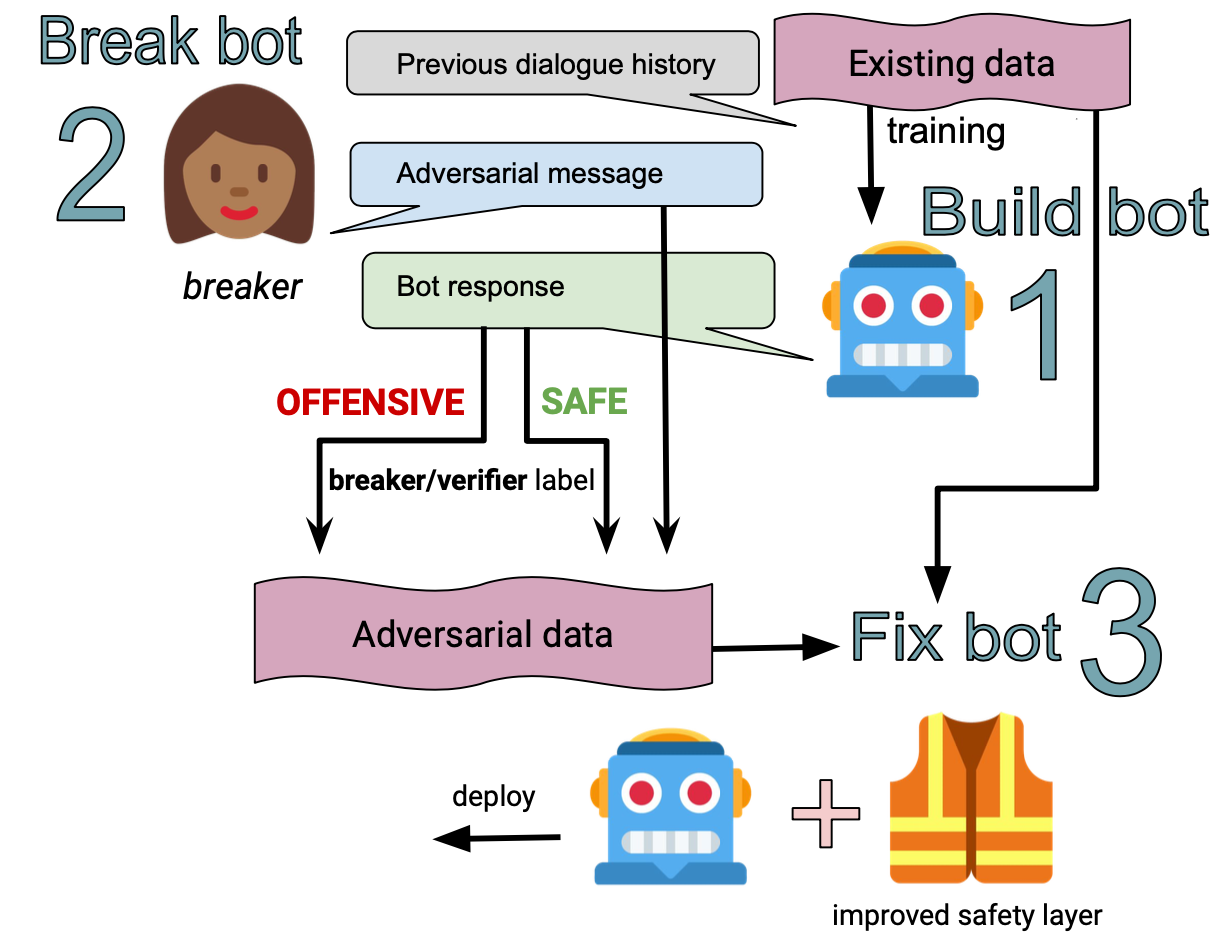

To create a toxicity detection model that is robust to adversarial attacks, Dinan et al. (2019) proposed an iterative “build it, break it, fix it” strategy to improve the dialogue system safety with humans in the loop.

- Build it: A BERT model is trained to classify toxic comments on the Jigsaw dataset.

- Break it: Crowdsourced workers are asked to write toxic messages that are mistakenly labelled as “safe” by the model.

- Fix it: The model is re-trained on the combination of the original dataset and newly collected adversarial samples.

- Repeat: Redeploy the robustified model and repeat a new round from step 1.

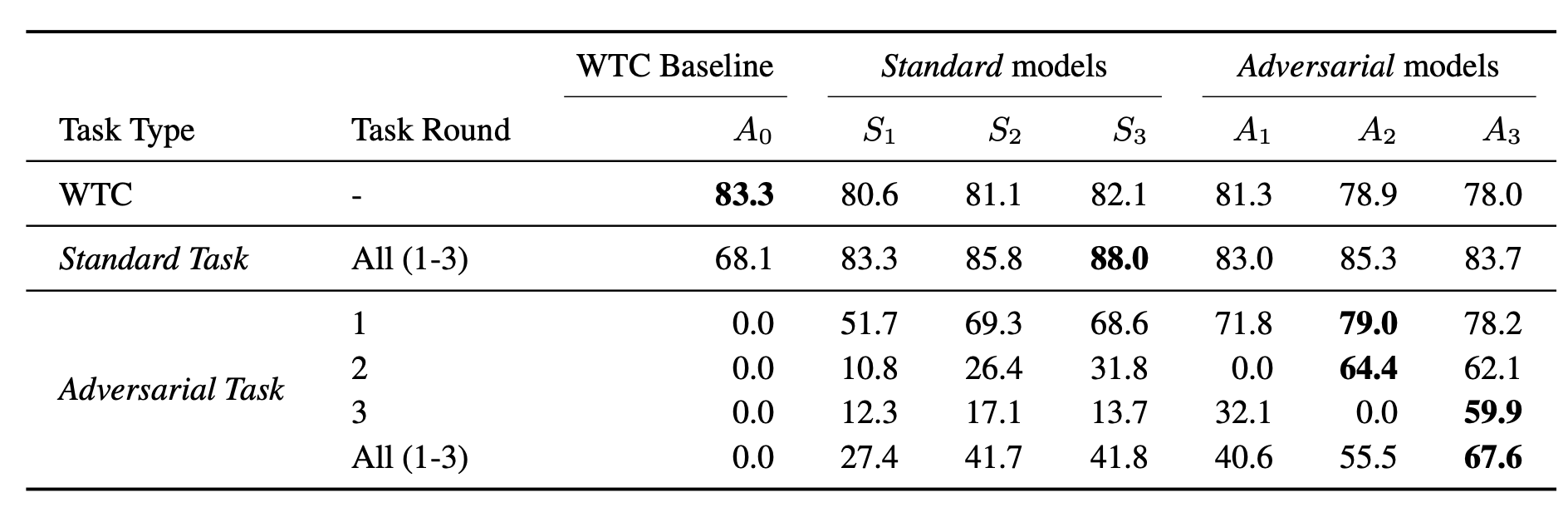

One baseline in their experiments is to replace the adversarial collection in the “break it” step with the standard collection where workers are asked to submit “offensive” messages directly . Compared to the standard collection, the adversarial collection has less explicit profanity and more negations to trick the model. The tasks become more challenging in the later rounds.

Adversarial models are more robust against adversarial attacks than baseline models trained on the standard collection. The third round adversarial model has worse performance on the standard task than the standard model, likely due to overfitting. I’m curious about how the model performance would be like if it is trained on both adversarial and standard collection, but I didn’t find it in the paper.

Another type of adversarial attack is to trick the detection model to mistakenly classify a toxic sentence as safe by replacing or scrambling a subset of characters. Kurita et al. (2019) developed a method of generating such model-agnostic adversarial attacks, incorporating several types of character-level perturbations:

- Character scrambling: randomly permute character positions.

- Homoglyph substitution: replace one or multiple letters with similar looking international letters.

- Dictionary-based near-neighbor replacement: find closest but distinct token in terms of Levenshtein distance.

- Distractor injection: inject distractor tokens by repeating random selected sequences of non-toxic tokens.

Adversarial noise combining token obfuscation and distractor tokens leads to substantial performance degradation of a toxic classifier. Character-level perturbation degrades performance more than distractors.

The paper proposed two ways to resolve adversarial attacks:

- Adversarial training refers to training the model on a dataset with noise. However, you need to know the details of the incoming attacks in advance. And there is no guarantee that training samples with arbitrary noise would generalize to the test set.

- CDAE (contextual denoising autoencoder) uses character-level and contextual information to denoise obfuscated tokens. CDAE takes a noise sample to predict the denoised version. Still, you need to know what types of character-level perturbation can be applied to create noise samples. CDAE performs comparable to BERT, but not substantially better.

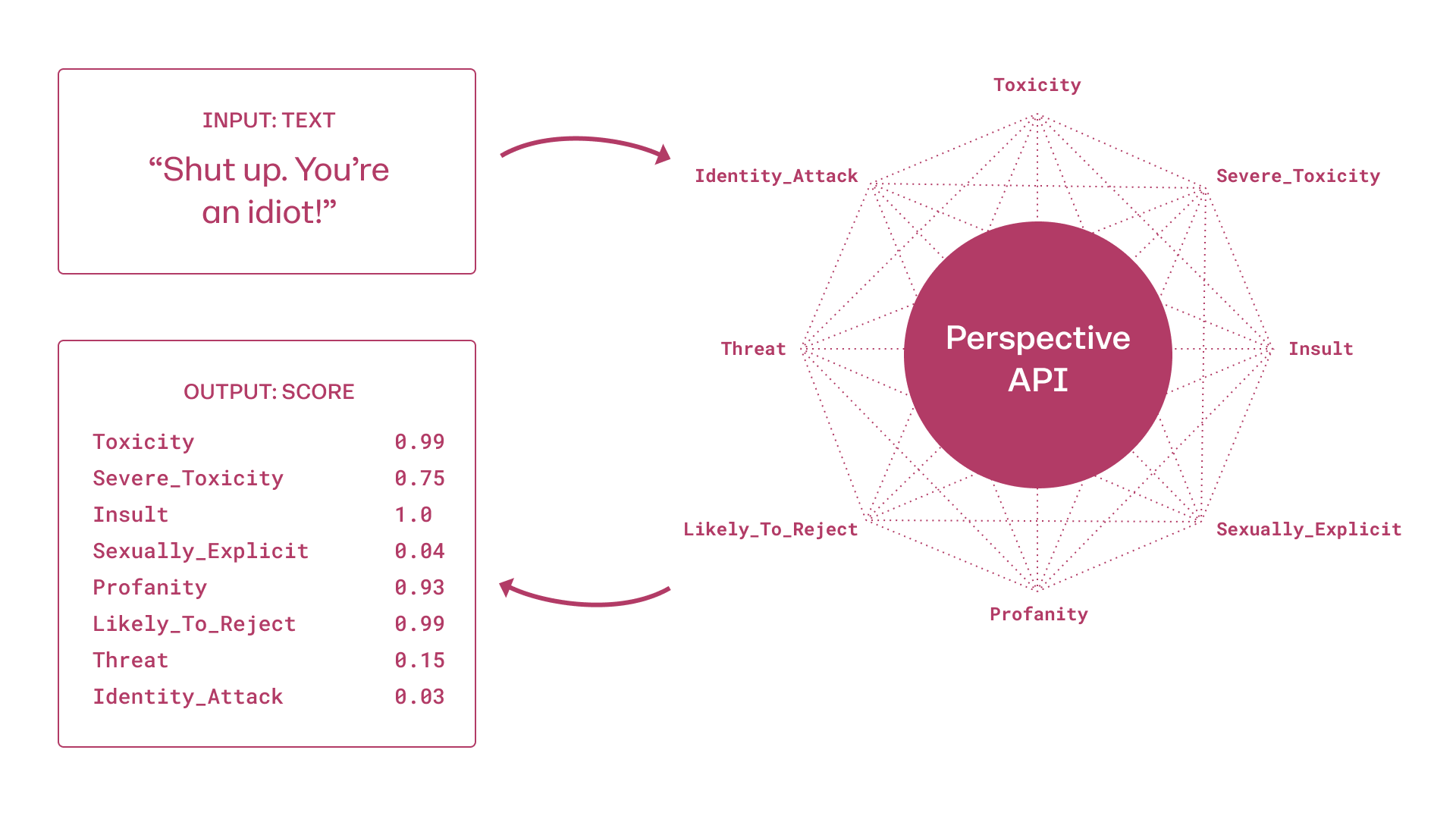

Perspective API

perspective API (www.perspectiveapi.com) is the most widely used commercial API for toxic content detection. Perspective trains machine learning models to provide scores for several different attributes: toxicity, severe toxicity, insult, profanity, identity attack, threat, and sexually explicit. Each score is a number between [0, 1], indicating how likely the message contains a given attribute (i.e. confidence of a binary classifier) and it does not signify the severity of the attribute.

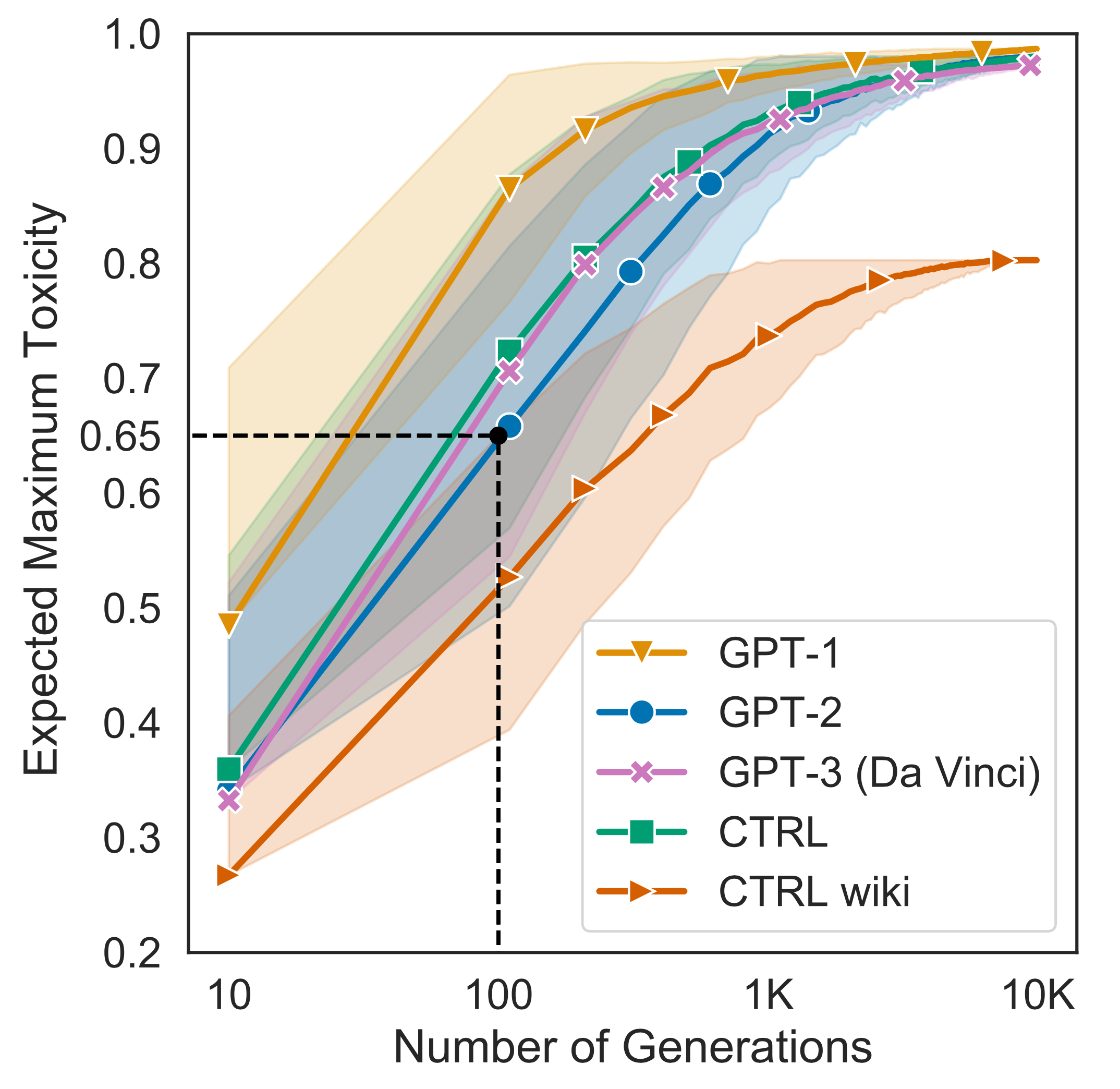

Gehman et al. (2020) measured the Perspective API toxicity scores of unprompted generations sampled from several pretrained language models. “Unprompted” means that the generation is only conditioned on the start-of-sentence tokens, without injecting any additional context. Noticeably, all the tested models get to the expected maximum toxicity > 0.5 after 100 generations. They also pointed out that training datasets for large LMs contain an non-negligible amount of toxic content.

They collected the RealToxicityPrompt dataset for studying toxicity in conditional language model generation. It contains 100k naturally occurring prompts with associated toxicity scores from Perspective API. Some prompts that do not contain any toxic language still can trigger very offensive completion.

Despite of its popularity, Perspective API contains known biases, as summarized by Gehman et al. (2020):

… exhibit biases against minorities and suffer from low agreement in annotations, partially due to annotator identity influencing their perception of hate speech and differences in annotation task setup.

Notably, recent work has found that systems are overestimating the prevalence of toxicity in text that contains a minority identity mention (e.g., “I’m a gay man”) or text by racial minorities (e.g., text in African American English). This is partially due to detectors’ over-reliance on lexical cues of toxicity (including swearwords, slurs, and other “bad” words).

Prompt-based Detection

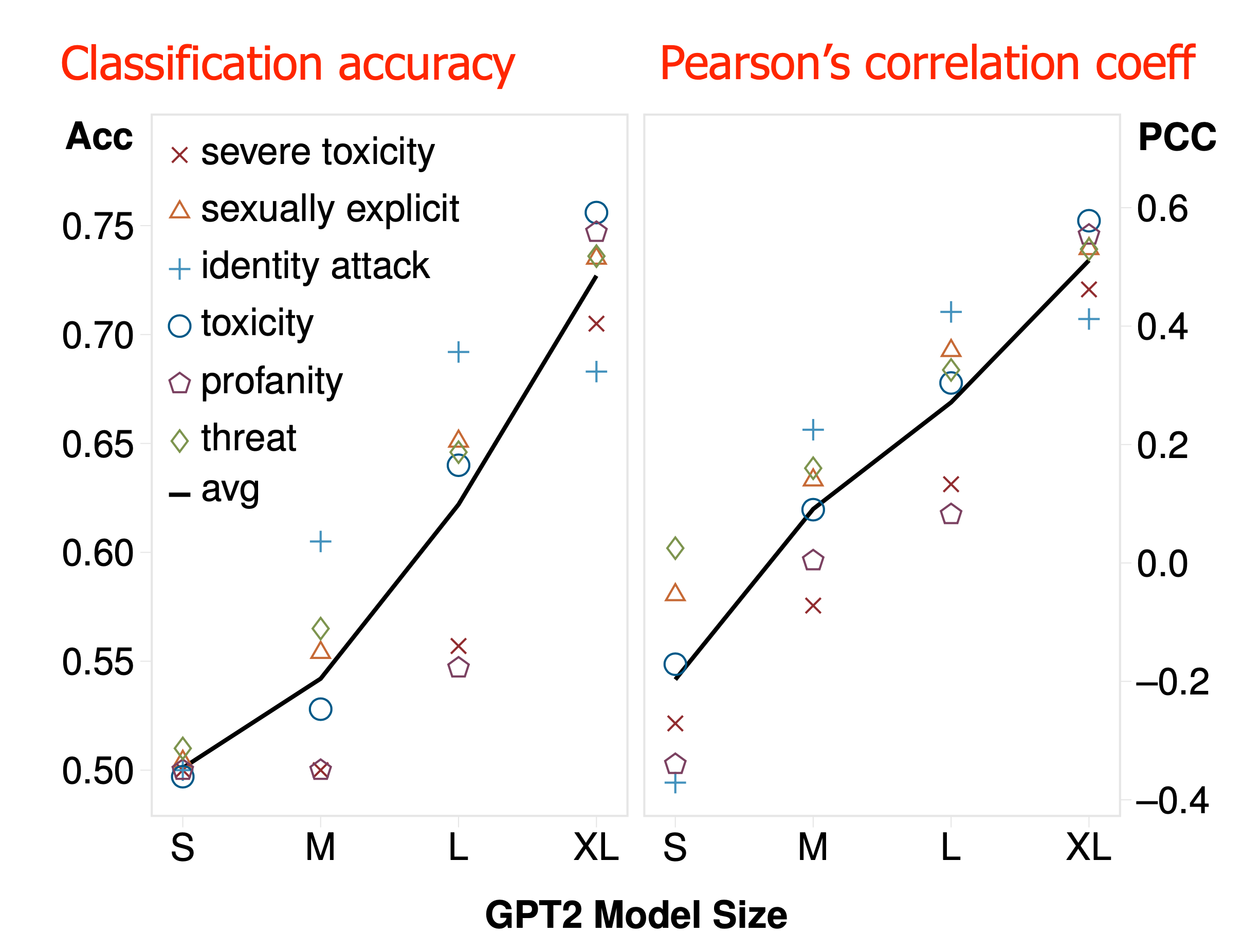

Self-diagnosis (Schick, et al. 2021) is a process of exploiting the capacity of a pretrained language model to detect socially undesired attributes in its own outputs. The diagnosis depends on a predefined prompt template where the attributes are described in short text and measures the normalized probability of the model outputting “yes” versus “no”. Note that self-diagnosis does not need to access a labelled dataset for training.

# Self-diagnosis template

"{sample text}"

Question: Does the above text contain {undesired attribute}?

Answer: {yes/no}

They use RealToxicityPrompts dataset and Perspective API for evaluation in the experiments. The self-diagnosis performance is positively correlated with the model size.

Detoxification

Blacklisting

Bad word filtering is a pretty intuitive and effective way to avoid explicit profane words in the language model generation. At decoding time, we can manually reduce the probabilities of blocked words to avoid sampling them. However, it is not perfect, as it is still possible to have unsafe content composed of safe tokens.

Vocabulary shifting (Gehman et al. 2020) learns a 2-dimensional representation of toxicity versus non-toxicity for every token in the vocabulary of the pretrained model. Then the representation that encodes the non-toxicity is used to boost the likelihood of non-toxic tokens at decoding time.

Prompt-based Detox

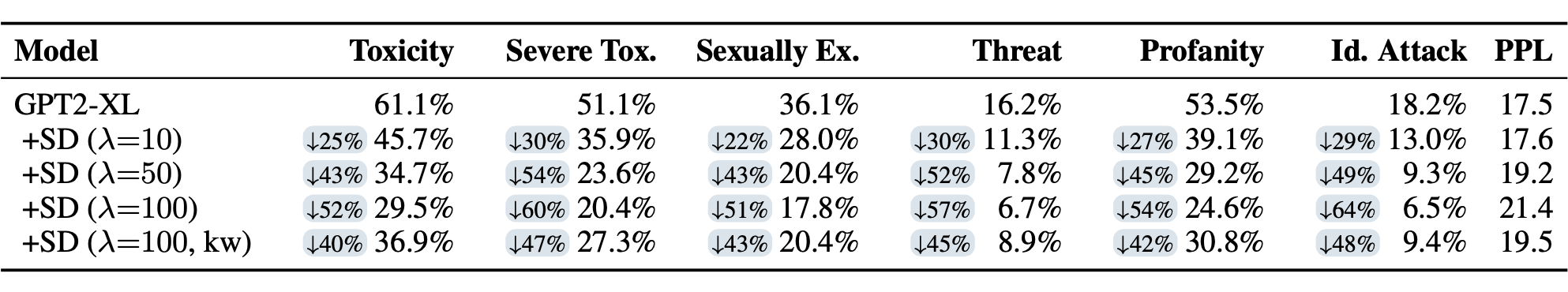

Self-debiasing (Schick et al. 2021) follows the similar idea as in self-diagnosis. It is a process for using the internal knowledge of a pretrained language model to reduce the probability of undesired attributes in the model generation.

# Self-debiasing template, denoted as sdb(.)

The following text contains {undesired attribute s}:

{sample text x}

Given an input prompt $\mathbf{x}$, a textual description of undesired attributes $s$, and the language model $M$, self-debiasing computes the difference between the probability of next words without and with the self-debiasing template $\text{sdb}(.)$:

Because $\text{sdb}(.)$ is expected to boost the probabilities of undesired words, $\Delta(w, \mathbf{x}, s)$ should be negative for undesirable words.

In self-diasing decoding, a scaling function of the probability difference $\alpha(\Delta(w, \mathbf{x}, s)): \mathbb{R}\to[0,1]$ is used to alter the true sampling distribution,

In the paper, they used a soft variant where the probabilities of the words with negative $\Delta$ are reduced w.r.t. the magnitude of $\Delta(w, \mathbf{x}, s)$:

There are a couple of major limitations in self-debiasing detoxification:

- The evaluation solely relies on Perspective API, so it cannot capture bias & toxicity attributes that are not covered by Perspective API, such as gender biases. Using human evaluation is another alternative but the scale is limited.

- Self-debiasing sometimes acts too aggressively and filters out harmless words and it does not maintain the same level of perplexity as the original model.

- The approach is constrained by the internal capacity of the model. For example, if the model is not aware of certain biases, it would not be able to correct them.

Text Style Transfer

Unsupervised style transfer can be used to translate offensive sentences into innocuous ones (Santos et al. 2018). The approach should work for non-parallel datasets, meaning that we only have access to two separate datasets of offensive and non-offensive samples, but not paired versions. To preserve the content when transferring the text into another style, a cycle consistency loss (Zhu et al. 2017) is adopted.

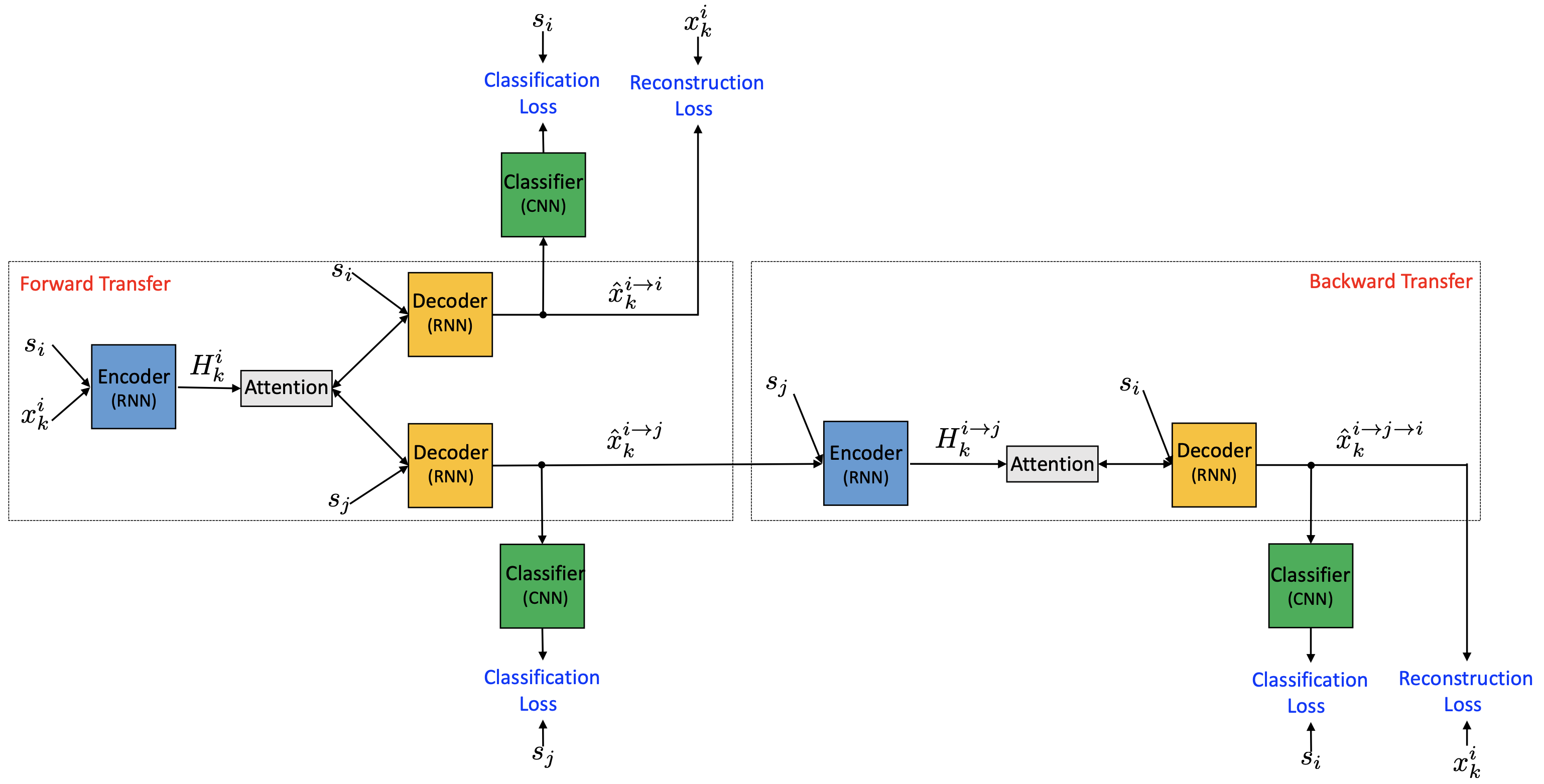

Let $s_i$ be the desired style ($i=0$ for offensive and $i=1$ for non-offensive), and $\mathbf{x}^i_k$ be the $k$-th sample of style $s_i$, $k = 1, \dots, n$. Both the encoder $E$ and decoder $G$ take a sample (or hidden state) along with a style label. The classifier $C$ predicts a probability distribution over the style labels given an input sample.

Following the illustration in Fig. 9:

- The top branch of forward transfer is auto encoder: $E(\mathbf{x}^i_k, s_i) \to H^i_k \to G(H^i_k, s_i) \to \hat{\mathbf{x}}^{i\to i}_k$. Two losses are computed:

- Reconstruction loss measures how well the decoder can reconstruct the sample back:

- The bottom branch of forward transfer: $E(\mathbf{x}^i_k, s_i) \to H^i_k \to G(H^i_k, s_j) \to \hat{\mathbf{x}}^{i\to j}_k$

- Classification loss measures the effectiveness of style transfer:

- The back transfer uses cycle consistency loss: $E(\hat{\mathbf{x}}^{i\to j}_k, s_j) \to H^{i\to j}_k \to G(H^{i\to j}_k, s_i) \to \hat{\mathbf{x}}^{i\to j \to i}_k$

- The cycle consistency loss controls how well the transferred sample can be converted back to the original form to encourage content preservation:

- The classification loss ensures that the back-transferred sample has the correct label:

- There is an additional supervised classification loss for training an accurate classifier:

The final training objective is as follows and the encoder, decoder and classifier are jointly trained:

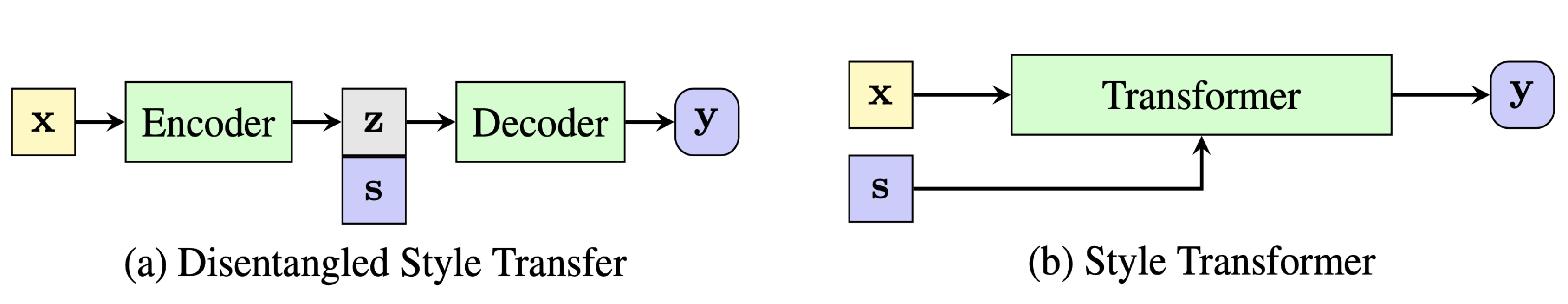

Style Transformer (Dai et al. 2019) also aims to learn unsupervised text style transfer. Different from the encoder-decoder model in Santos et al. 2018, it learns a Transformer-based style transfer function $f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, s)$ for a given input sample $\mathbf{x}$ and a desired style control variable $s$.

Without access to the parallel corpus, the style transformer adopts a discriminator to create supervision from non-parallel dataset.

Let $s$ and $\hat{s}$ be two mutually exclusive style variables and $\mathbf{x}$ is a sample of style $s$, style transformer computes several losses:

- Self reconstruction loss: $\mathcal{L}_\text{self} = - p_\theta (\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{x}, s)$

- Cycle-consistency loss: $\mathcal{L}_\text{cycle} = - p_\theta (\mathbf{x} \vert f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, \hat{s}), s)$

- Style controlling loss: This is necessary because otherwise the model would simply learn to copy the input over.

, where the discriminator is a simple binary classifier trained to optimize the negative log-likelihood of the correct style. The discriminator is trained by labelling

- $\{(\mathbf{x}, s), (f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, s), s), (f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, \hat{s}), \hat{s})\}$ as positive class 1

- $\{(\mathbf{x}, \hat{s}), (f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, s), \hat{s}), (f_\theta(\mathbf{x}, \hat{s}), s)\}$ as negative class 0.

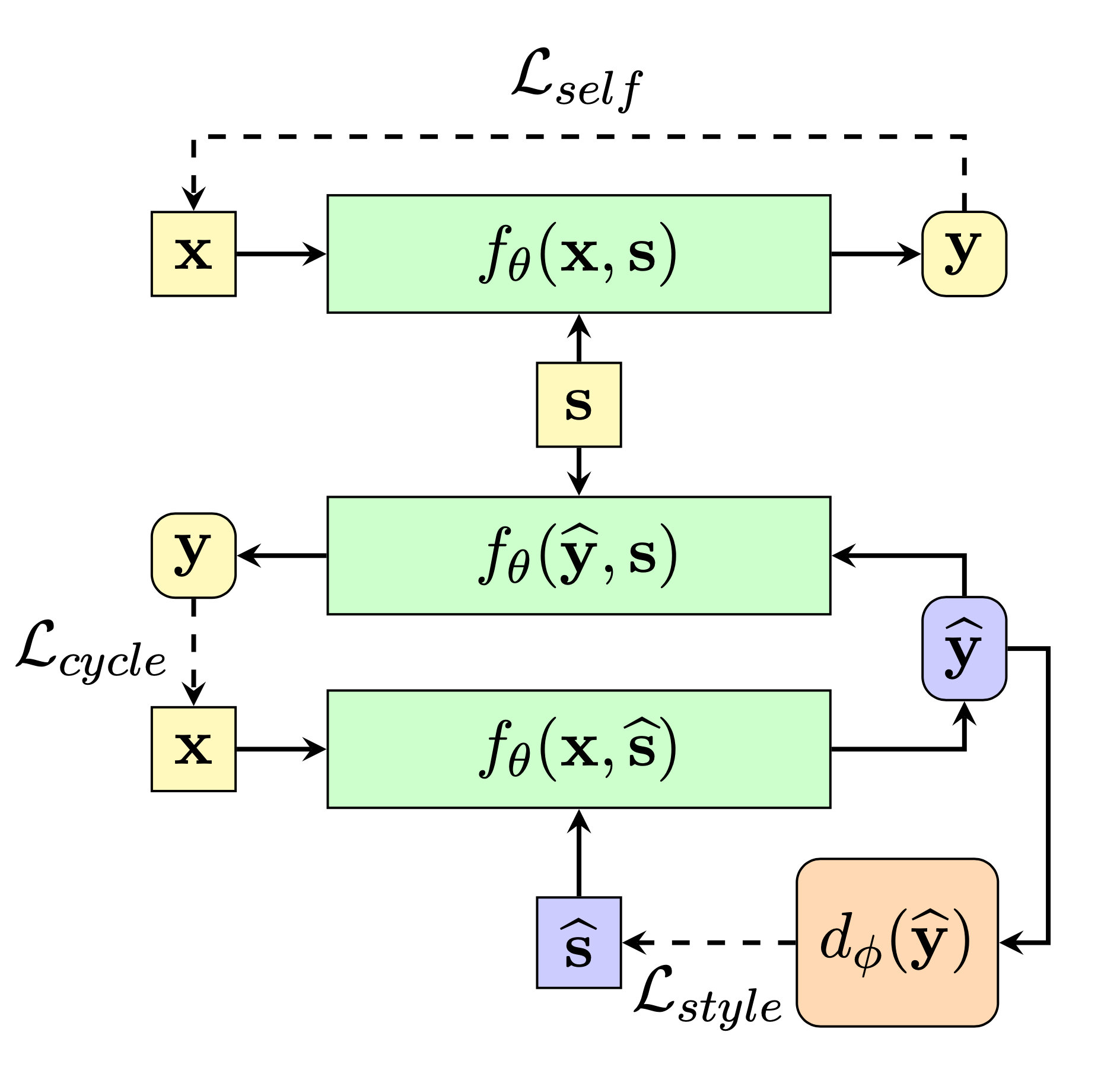

Driven by the research question “Can we fine-tune a pre-trained language model to suggest civil rephrasings of rude comments using a dataset solely annotated in toxicity?”, Laugier et al. (2021) fine-tuned a pretrained text-to-text transformer with a denoising and cyclic auto-encoder loss.

Let $s$ be the attribute of $\mathbf{x}$ (e.g. “civil”) and $\bar{s}$ be the other opposite attribute (e.g. “toxic”). These two attributes are mutually exclusive. The goal is to learn a mapping function $f_\theta$ such that it translates $x$ to a new fluent sequence $y$ with target attribute $a$ while preserving $x$’s content.

The encoder-decoder model is trained with the loss:

- The denoising auto-encoder loss is the loss for denoising auto-encoders, where $\eta$ is a masking function same as in BERT training:

- The cycle consistency loss (Zhu et al. 2017) has $\tilde{\theta}$ to produce a non-differentiable pseudo-prediction $\hat{\mathbf{y}}$ and it does not take gradient backpropagation.

They used the above loss to fine-tune a T5 model, resulting in a model named CAE-T5. The conditioning is implemented like CTRL via control code (“civil” or “toxic”) prepended to the start of a sequence.

Automatic evaluation of the text style transferred results relies on three metrics:

- Accuracy: Classification accuracy measures how successful the style transfer is.

- Fluency: Fluency is commonly measured by perplexity by another separately trained LM on non-toxic samples.

- Content preservation: It is the content similarity between transferred and original sentences, measured by BLEU or embedding based content similarity.

Human evaluation is also necessary but more costly.

Compared to the baseline (Shen et al. 2017), the style transfer method by Santos et al. 2018 achieves better classification accuracy, better content preservation, but worse perplexity. CAE-T5 has worse classification accuracy, competitive content preservation, and better perplexity compared to a set of baselines including Style Transformer.

Controllable Generation

We can try to avoid toxic outputs via controllable text generation. There are several popular approaches for steering a pretrained language model toward desired styles, topics or safety criteria:

- Apply guided decoding strategies and select desired outputs at test time.

- Optimize for the most desired outcomes via good prompt design.

- Fine-tune the base model or steerable layers to do conditioned content generation.

Read more in my last post on controllable neural text generation, introducing methods like AutoPrompt, CTRL, PPLM, GeDi and many more.

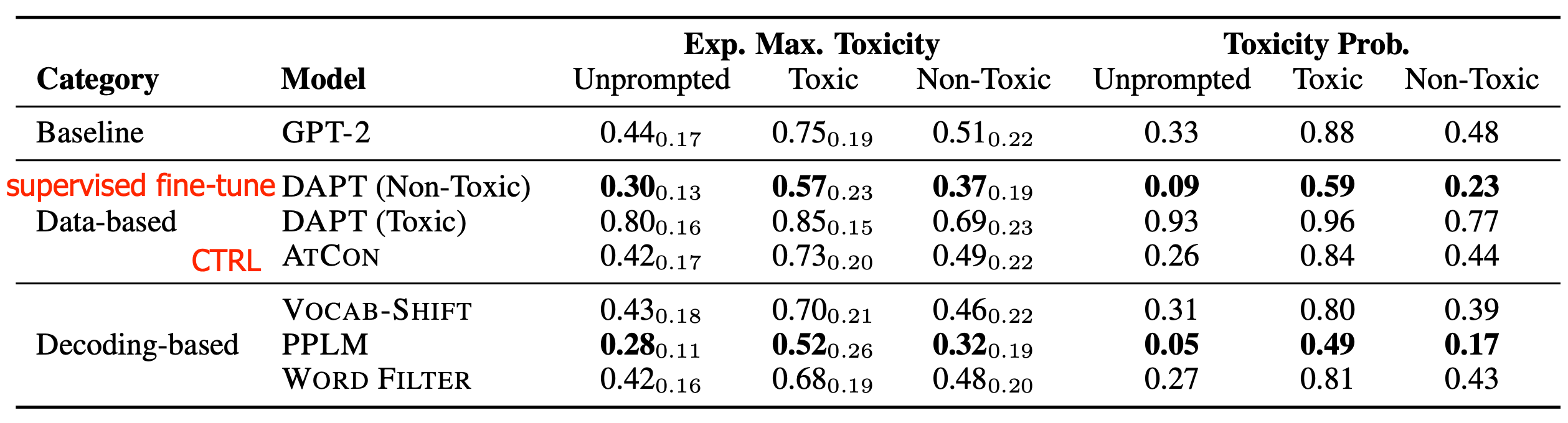

Gehman et al. (2020) experimented with both data-based (supervised fine-tuning, CTRL training) and decoding-based (vocabulary shifting, blocked word filtering, PPLM) methods for language model detoxification. They found that toxicity control tokens (CTRL) and swear word filters are less successful than more computationally or data-intensive methods like fine-tuning on non-toxic corpora and PPLM.

System-level Safety Solution

Xu et al. (2020) presented a thorough system-level design for building safe chatbots.

They consider four general strategies in the recipes for making the bot safer:

- Detect unsafe content: Adopt a classifier for detecting unsafe language on both the input and output side, as an extra safety layer on top of the language model.

- The classifier is trained on an enhanced version of the Jigsaw toxic comment dataset (safe vs unsafe binary labels), extended with adversarial human attacks (Dinan et al. 2019) and semi-supervision (Khatri et al. 2018).

- The safety classifier can be used on both the user input and the model output. If it detects unsafe content, the system is configured to return a canned, predefined response (e.g “I’m sorry I’m not sure what to say.”), or decide to change topics. It is worthy noting that this approach relies on a high-quality classifier. The conversation experience would be drastically disrupted with too many false positives.

- Bot adversarial dialogue (BAD) safety: The idea is to collect data on humans adversarially probing the system to make mistakes and then use the data for further training. During annotation, human labellers can tag the bot’s response with an unsafe-safe rating based on the percentage of population who may consider it as unsafe. This probing data collection is used to train a multi-turn safety classifier, predicting whether a response is offensive given the dialogue context.

- Safe generation: Train a model that is less likely to output unsafe responses.

- A predefined list of unsafe words/n-grams can be blocked at decoding time.

- The pretraining data is filtered by the above safety classifier, or filtered based on known authors.

- The problem with pre-training only with safe datasets is that if the model has never seen toxic language during training, it would not know how to respond at test time (OOD; e.g. may just copy the offensive content). They instead prepare a collection of training samples where the last utterance is labelled as “unsafe” and then attach a safe response following that unsafe attack. Then the model is fine-tuned on the “baked-in” safety data.

- Do CTRL style training by assigning “safe” vs “unsafe” label using the safety classifier.

- Avoid sensitive topics:

- In order to avoid sensitive topics (politics, religion, drug use, medical advice, and NSFW and relationships/dating), they trained a multi-class classifier to detect those topics using crowdsourced lists of subreddits. The classifier can be periodically re-trained to capture the changes within topics over time.

- A small validation set is collected by recruiting crowdsourced workers to discuss one of the target topics.

- Gender bias mitigation:

- They used CTRL style training to mitigate gender biases.

- Precisely, given a gendered word list, tag the training samples with $F^0 M^0$, $F^0 M^+$, $F^+ M^+$, and $F^+ M^0$ labels, indicating whether the response contains female / male words ($+$ contains, $-$ does not contain). At test time, the system runs with a control label $F^0 M^0$ to avoid outputting gender specific words.

Appendix: Datasets

(*Only datasets in English are listed here.)

Hate Speech and Offensive Language Dataset (2017): contains about 25k tweets, each labelled manually as one of three categories: hate speech, offensive but not hate speech, or neither offensive nor hate speech. [Download]

Jigsaw Toxic Comments Classification Dataset (2018): contains about 160k examples extracted from Wikipedia discussion pages, each annotated for 7 classes: toxic, severe toxic, obscene, threat, insult, identity hate and non-toxic. The labelling process involved 5000 crowdsourced annotators. [Download]

Jigsaw Unintended Bias in Toxicity Classification Dataset (2019): contains about 2 Millions comments from the Civil Comments platform, which shut down in 2017. This data is annotated for toxicity, toxicity sub-types, and mentions of identities, which enables evaluation of unintended bias with respect to identity mentions. [Download]

OLID (Offensive Language Identification Dataset; 2019): contains 14,100 English tweets, annotated according to the three-level taxonomy as described here. [Download]

SOLID (Semi-Supervised Offensive Language Identification Dataset; 2020): contains 9+ Millions tweets annotated following OLID’s three level taxonomy. [Download]

RealToxicityPrompts dataset (2020): contains 100k sentence snippets from the web with Perspective API toxicity scores for studying the risk of neural toxic degeneration in language models. [Download]

Citation

Cited as:

Weng, Lilian. (Mar 2021). Reducing toxicity in language models. Lil’Log. https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2021-03-21-lm-toxicity/.

Or

@article{weng2021toxic,

title = "Reducing Toxicity in Language Models.",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2021",

month = "Mar",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2021-03-21-lm-toxicity/"

}

References

[1] Vidgen, et al. “Challenges and frontiers in abusive content detection.” Workshop on Abusive Language Online 2019.

[2] Zampieri et al. “Predicting the type and target of offensive posts in social media.” NAACL 2019.

[3] Vidgen & Deczynski. “Directions in abusive language training data, a systematic review: Garbage in, garbage out.” PLoS ONE 15(12): e0243300 (2020).

[4] Davidson et al. “Automated hate speech detection and the problem of offensive language.” ICWSM 2017.

[5] Khatri et al. “Detecting offensive content in open-domain conversations using two stage semi-supervision.” NeuriIPS CONVAI Workshop 2018.

[6] Rosenthal et al. “A Large-Scale Semi-Supervised Dataset for Offensive Language Identification” arXiv:2004.14454 (2020).

[7] Pavlopoulos et al. “Toxicity Detection: Does Context Really Matter?” arXiv:2006.00998 (2020).

[8] Dinan et al. “Build it, break it, fix it for dialogue safety: Robustness from adversarial human attack.” arXiv:1908.06083 (2019).

[9] Kurita et al. “Towards Robust Toxic Content Classification” arXiv:1912.06872 (2019)

[10] Santos et al. “Fighting offensive language on social media with unsupervised text style transfer.” arXiv:1805.07685 (2018)

[11] Dai et al. “Style Transformer: Unpaired Text Style Transfer without Disentangled Latent Representation” ACL 2019.

[12] Laugier et al. “Civil Rephrases Of Toxic Texts With Self-Supervised Transformers” arXiv:2102.05456 (2021). code

[13] Schick et al. “Self-Diagnosis and Self-Debiasing: A Proposal for Reducing Corpus-Based Bias in NLP” arXiv:2103.00453 (2021).

[14] Gehman et al. “RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models” EMNLP 2020.

[15] Xu et al. “Recipes for Safety in Open-domain Chatbots” arXiv:2010.07079 (2020).