The full implementation is available in lilianweng/deep-reinforcement-learning-gym

In the previous two posts, I have introduced the algorithms of many deep reinforcement learning models. Now it is the time to get our hands dirty and practice how to implement the models in the wild. The implementation is gonna be built in Tensorflow and OpenAI gym environment. The full version of the code in this tutorial is available in [lilian/deep-reinforcement-learning-gym].

Environment Setup

- Make sure you have Homebrew installed:

/usr/bin/ruby -e "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install)"

- I would suggest starting a virtualenv for your development. It makes life so much easier when you have multiple projects with conflicting requirements; i.e. one works in Python 2.7 while the other is only compatible with Python 3.5+.

# Install python virtualenv

brew install pyenv-virtualenv

# Create a virtual environment of any name you like with Python 3.6.4 support

pyenv virtualenv 3.6.4 workspace

# Activate the virtualenv named "workspace"

pyenv activate workspace

[*] For every new installation below, please make sure you are in the virtualenv.

- Install OpenAI gym according to the instruction. For a minimal installation, run:

git clone https://github.com/openai/gym.git

cd gym

pip install -e .

If you are interested in playing with Atari games or other advanced packages, please continue to get a couple of system packages installed.

brew install cmake boost boost-python sdl2 swig wget

For Atari, go to the gym directory and pip install it. This post is pretty helpful if you have troubles with ALE (arcade learning environment) installation.

pip install -e '.[atari]'

- Finally clone the “playground” code and install the requirements.

git clone git@github.com:lilianweng/deep-reinforcement-learning-gym.git

cd deep-reinforcement-learning-gym

pip install -e . # install the "playground" project.

pip install -r requirements.txt # install required packages.

Gym Environment

The OpenAI Gym toolkit provides a set of physical simulation environments, games, and robot simulators that we can play with and design reinforcement learning agents for. An environment object can be initialized by gym.make("{environment name}":

import gym

env = gym.make("MsPacman-v0")

The formats of action and observation of an environment are defined by env.action_space and env.observation_space, respectively.

Types of gym spaces:

gym.spaces.Discrete(n): discrete values from 0 to n-1.gym.spaces.Box: a multi-dimensional vector of numeric values, the upper and lower bounds of each dimension are defined byBox.lowandBox.high.

We interact with the env through two major api calls:

ob = env.reset()

- Resets the env to the original setting.

- Returns the initial observation.

ob_next, reward, done, info = env.step(action)

- Applies one action in the env which should be compatible with

env.action_space. - Gets back the new observation

ob_next(env.observation_space), a reward (float), adoneflag (bool), and other meta information (dict). Ifdone=True, the episode is complete and we should reset the env to restart. Read more here.

Naive Q-Learning

Q-learning (Watkins & Dayan, 1992) learns the action value (“Q-value”) and update it according to the Bellman equation. The key point is while estimating what is the next action, it does not follow the current policy but rather adopt the best Q value (the part in red) independently.

In a naive implementation, the Q value for all (s, a) pairs can be simply tracked in a dict. No complicated machine learning model is involved yet.

from collections import defaultdict

Q = defaultdict(float)

gamma = 0.99 # Discounting factor

alpha = 0.5 # soft update param

env = gym.make("CartPole-v0")

actions = range(env.action_space)

def update_Q(s, r, a, s_next, done):

max_q_next = max([Q[s_next, a] for a in actions])

# Do not include the next state's value if currently at the terminal state.

Q[s, a] += alpha * (r + gamma * max_q_next * (1.0 - done) - Q[s, a])

Most gym environments have a multi-dimensional continuous observation space (gym.spaces.Box). To make sure our Q dictionary will not explode by trying to memorize an infinite number of keys, we apply a wrapper to discretize the observation. The concept of wrappers is very powerful, with which we are capable to customize observation, action, step function, etc. of an env. No matter how many wrappers are applied, env.unwrapped always gives back the internal original environment object.

import gym

class DiscretizedObservationWrapper(gym.ObservationWrapper):

"""This wrapper converts a Box observation into a single integer.

"""

def __init__(self, env, n_bins=10, low=None, high=None):

super().__init__(env)

assert isinstance(env.observation_space, Box)

low = self.observation_space.low if low is None else low

high = self.observation_space.high if high is None else high

self.n_bins = n_bins

self.val_bins = [np.linspace(l, h, n_bins + 1) for l, h in

zip(low.flatten(), high.flatten())]

self.observation_space = Discrete(n_bins ** low.flatten().shape[0])

def _convert_to_one_number(self, digits):

return sum([d * ((self.n_bins + 1) ** i) for i, d in enumerate(digits)])

def observation(self, observation):

digits = [np.digitize([x], bins)[0]

for x, bins in zip(observation.flatten(), self.val_bins)]

return self._convert_to_one_number(digits)

env = DiscretizedObservationWrapper(

env,

n_bins=8,

low=[-2.4, -2.0, -0.42, -3.5],

high=[2.4, 2.0, 0.42, 3.5]

)

Let’s plug in the interaction with a gym env and update the Q function every time a new transition is generated. When picking the action, we use ε-greedy to force exploration.

import gym

import numpy as np

n_steps = 100000

epsilon = 0.1 # 10% chances to apply a random action

def act(ob):

if np.random.random() < epsilon:

# action_space.sample() is a convenient function to get a random action

# that is compatible with this given action space.

return env.action_space.sample()

# Pick the action with highest q value.

qvals = {a: q[state, a] for a in actions}

max_q = max(qvals.values())

# In case multiple actions have the same maximum q value.

actions_with_max_q = [a for a, q in qvals.items() if q == max_q]

return np.random.choice(actions_with_max_q)

ob = env.reset()

rewards = []

reward = 0.0

for step in range(n_steps):

a = act(ob)

ob_next, r, done, _ = env.step(a)

update_Q(ob, r, a, ob_next, done)

reward += r

if done:

rewards.append(reward)

reward = 0.0

ob = env.reset()

else:

ob = ob_next

Often we start with a high epsilon and gradually decrease it during the training, known as “epsilon annealing”. The full code of QLearningPolicy is available here.

Deep Q-Network

Deep Q-network is a seminal piece of work to make the training of Q-learning more stable and more data-efficient, when the Q value is approximated with a nonlinear function. Two key ingredients are experience replay and a separately updated target network.

The main loss function looks like the following,

The Q network can be a multi-layer dense neural network, a convolutional network, or a recurrent network, depending on the problem. In the full implementation of the DQN policy, it is determined by the model_type parameter, one of (“dense”, “conv”, “lstm”).

In the following example, I’m using a 2-layer densely connected neural network to learn Q values for the cart pole balancing problem.

import gym

env = gym.make('CartPole-v1')

# The observation space is `Box(4,)`, a 4-element vector.

observation_size = env.observation_space.shape[0]

We have a helper function for creating the networks below:

import tensorflow as tf

def dense_nn(inputs, layers_sizes, scope_name):

"""Creates a densely connected multi-layer neural network.

inputs: the input tensor

layers_sizes (list<int>): defines the number of units in each layer. The output

layer has the size layers_sizes[-1].

"""

with tf.variable_scope(scope_name):

for i, size in enumerate(layers_sizes):

inputs = tf.layers.dense(

inputs,

size,

# Add relu activation only for internal layers.

activation=tf.nn.relu if i < len(layers_sizes) - 1 else None,

kernel_initializer=tf.contrib.layers.xavier_initializer(),

name=scope_name + '_l' + str(i)

)

return inputs

The Q-network and the target network are updated with a batch of transitions (state, action, reward, state_next, done_flag). The input tensors are:

batch_size = 32 # A tunable hyperparameter.

states = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(batch_size, observation_size), name='state')

states_next = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(batch_size, observation_size), name='state_next')

actions = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, shape=(batch_size,), name='action')

rewards = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(batch_size,), name='reward')

done_flags = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(batch_size,), name='done')

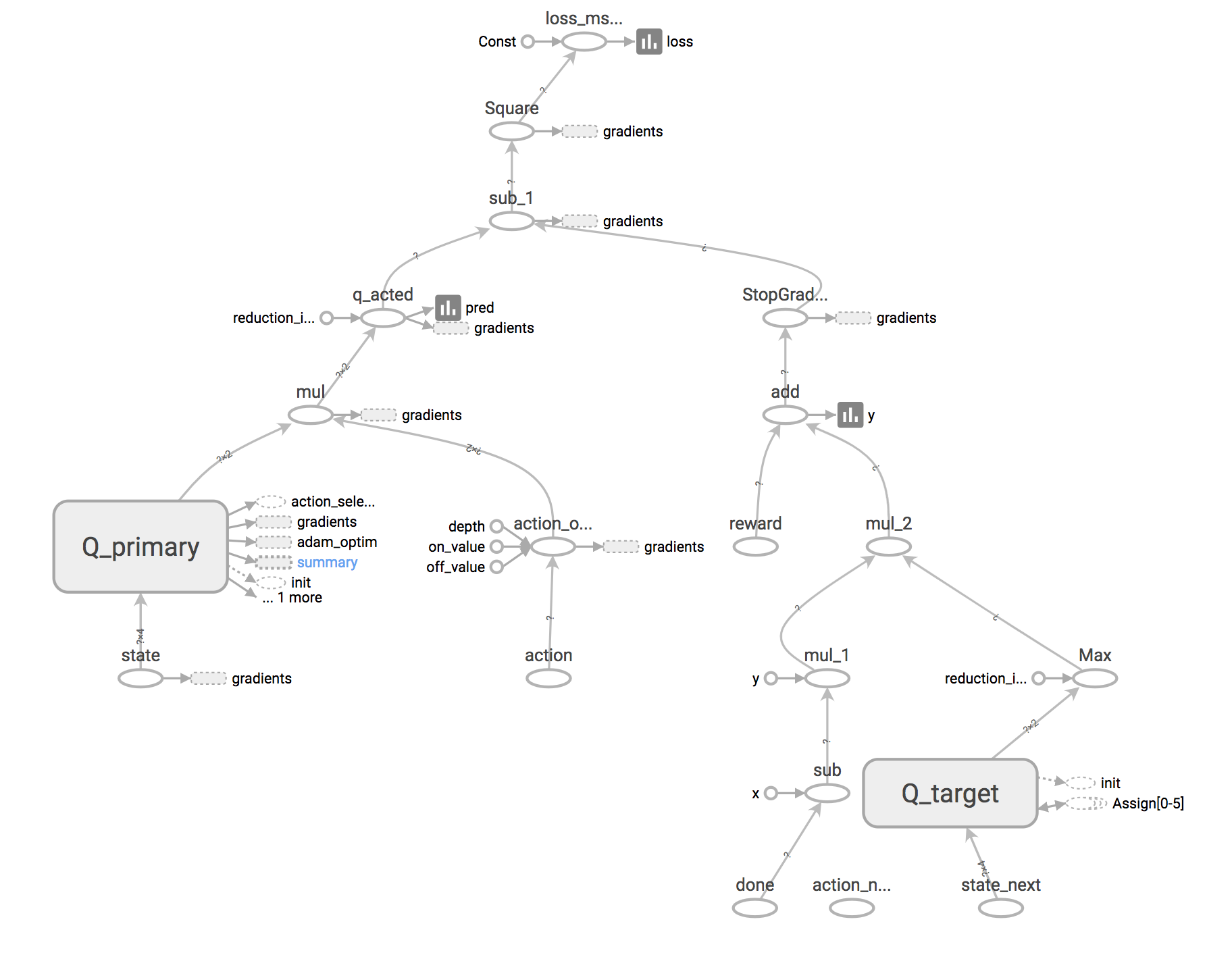

We have two networks of the same structure. Both have the same network architectures with the state observation as the inputs and Q values over all the actions as the outputs.

q = dense(states, [32, 32, 2], name='Q_primary')

q_target = dense(states_next, [32, 32, 2], name='Q_target')

The target network “Q_target” takes the states_next tensor as the input, because we use its prediction to select the optimal next state in the Bellman equation.

# The prediction by the primary Q network for the actual actions.

action_one_hot = tf.one_hot(actions, act_size, 1.0, 0.0, name='action_one_hot')

pred = tf.reduce_sum(q * action_one_hot, reduction_indices=-1, name='q_acted')

# The optimization target defined by the Bellman equation and the target network.

max_q_next_by_target = tf.reduce_max(q_target, axis=-1)

y = rewards + (1. - done_flags) * gamma * max_q_next_by_target

# The loss measures the mean squared error between prediction and target.

loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(pred - tf.stop_gradient(y)), name="loss_mse_train")

optimizer = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(0.001).minimize(loss, name="adam_optim")

Note that tf.stop_gradient() on the target y, because the target network should stay fixed during the loss-minimizing gradient update.

The target network is updated by copying the primary Q network parameters over every C number of steps (“hard update”) or polyak averaging towards the primary network (“soft update”)

# Get all the variables in the Q primary network.

q_vars = tf.get_collection(tf.GraphKeys.GLOBAL_VARIABLES, scope="Q_primary")

# Get all the variables in the Q target network.

q_target_vars = tf.get_collection(tf.GraphKeys.GLOBAL_VARIABLES, scope="Q_target")

assert len(q_vars) == len(q_target_vars)

def update_target_q_net_hard():

# Hard update

sess.run([v_t.assign(v) for v_t, v in zip(q_target_vars, q_vars)])

def update_target_q_net_soft(tau=0.05):

# Soft update: polyak averaging.

sess.run([v_t.assign(v_t * (1. - tau) + v * tau) for v_t, v in zip(q_target_vars, q_vars)])

Double Q-Learning

If we look into the standard form of the Q value target, $Y(s, a) = r + \gamma \max_{a’ \in \mathcal{A}} Q_\theta (s’, a’)$, it is easy to notice that we use $Q_\theta$ to select the best next action at state s’ and then apply the action value predicted by the same $Q_\theta$. This two-step reinforcing procedure could potentially lead to overestimation of an (already) overestimated value, further leading to training instability. The solution proposed by double Q-learning (Hasselt, 2010) is to decouple the action selection and action value estimation by using two Q networks, $Q_1$ and $Q_2$: when $Q_1$ is being updated, $Q_2$ decides the best next action, and vice versa.

To incorporate double Q-learning into DQN, the minimum modification (Hasselt, Guez, & Silver, 2016) is to use the primary Q network to select the action while the action value is estimated by the target network:

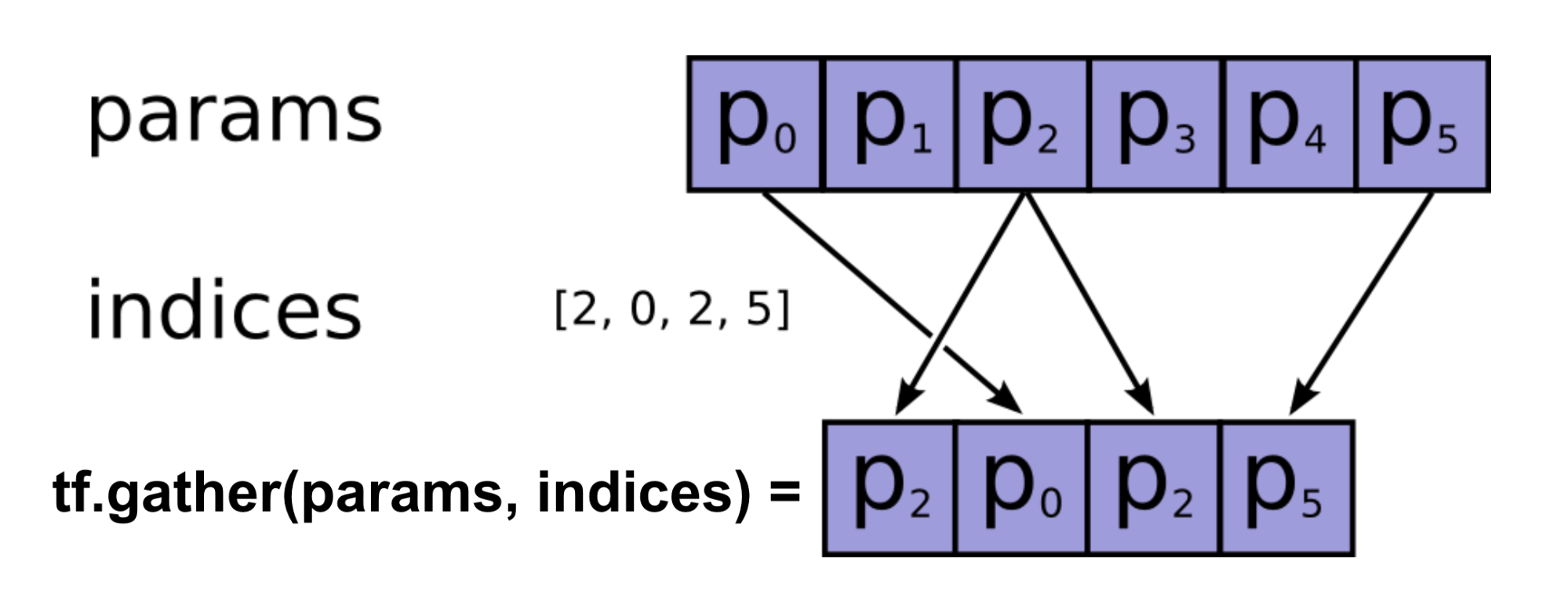

In the code, we add a new tensor for getting the action selected by the primary Q network as the input and a tensor operation for selecting this action.

actions_next = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, shape=(None,), name='action_next')

actions_selected_by_q = tf.argmax(q, axis=-1, name='action_selected')

The prediction target y in the loss function becomes:

actions_next_flatten = actions_next + tf.range(0, batch_size) * q_target.shape[1]

max_q_next_target = tf.gather(tf.reshape(q_target, [-1]), actions_next_flatten)

y = rewards + (1. - done_flags) * gamma * max_q_next_by_target

Here I used tf.gather() to select the action values of interests.

During the episode rollout, we compute the actions_next by feeding the next states’ data into the actions_selected_by_q operation.

# batch_data is a dict with keys, ‘s', ‘a', ‘r', ‘s_next' and ‘done', containing a batch of transitions.

actions_next = sess.run(actions_selected_by_q, {states: batch_data['s_next']})

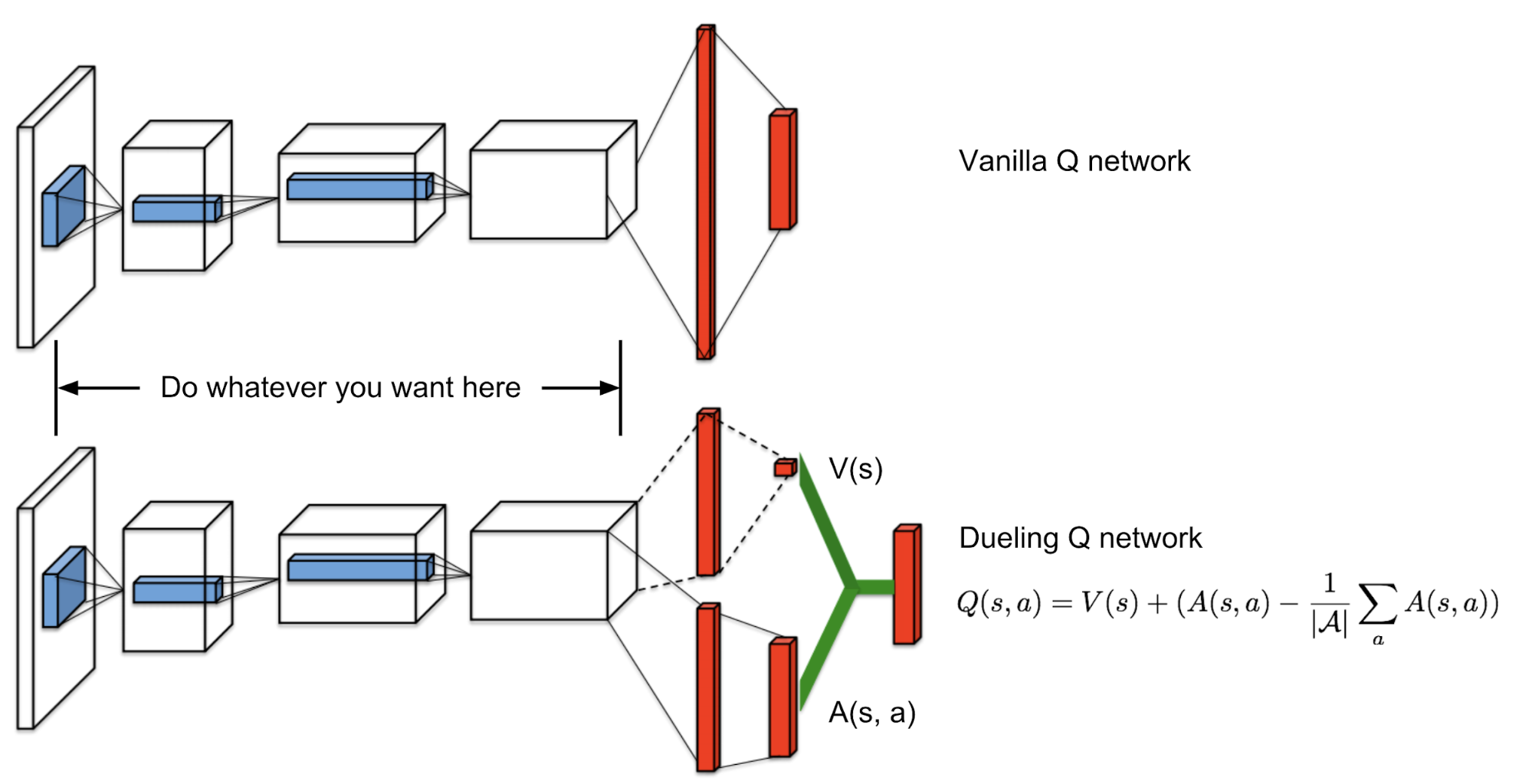

Dueling Q-Network

The dueling Q-network (Wang et al., 2016) is equipped with an enhanced network architecture: the output layer branches out into two heads, one for predicting state value, V, and the other for advantage, A. The Q-value is then reconstructed, $Q(s, a) = V(s) + A(s, a)$.

To make sure the estimated advantage values sum up to zero, $\sum_a A(s, a)\pi(a \vert s) = 0$, we deduct the mean value from the prediction.

The code change is straightforward:

q_hidden = dense_nn(states, [32], name='Q_primary_hidden')

adv = dense_nn(q_hidden, [32, env.action_space.n], name='Q_primary_adv')

v = dense_nn(q_hidden, [32, 1], name='Q_primary_v')

# Average dueling

q = v + (adv - tf.reduce_mean(adv, reduction_indices=1, keepdims=True))

Check the code for the complete flow.

Monte-Carlo Policy Gradient

I reviewed a number of popular policy gradient methods in my last post. Monte-Carlo policy gradient, also known as REINFORCE, is a classic on-policy method that learns the policy model explicitly. It uses the return estimated from a full on-policy trajectory and updates the policy parameters with policy gradient.

The returns are computed during rollouts and then fed into the Tensorflow graph as inputs.

# Inputs

states = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(None, obs_size), name='state')

actions = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, shape=(None,), name='action')

returns = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(None,), name='return')

The policy network is contructed. We update the policy parameters by minimizing the loss function, $\mathcal{L} = - (G_t - V(s)) \log \pi(a \vert s)$. tf.nn.sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits() asks for the raw logits as inputs, rather then the probabilities after softmax, and that’s why we do not have a softmax layer on top of the policy network.

# Policy network

pi = dense_nn(states, [32, 32, env.action_space.n], name='pi_network')

sampled_actions = tf.squeeze(tf.multinomial(pi, 1)) # For sampling actions according to probabilities.

with tf.variable_scope('pi_optimize'):

loss_pi = tf.reduce_mean(

returns * tf.nn.sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(

logits=pi, labels=actions), name='loss_pi')

optim_pi = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(0.001).minimize(loss_pi, name='adam_optim_pi')

During the episode rollout, the return is calculated as follows:

# env = gym.make(...)

# gamma = 0.99

# sess = tf.Session(...)

def act(ob):

return sess.run(sampled_actions, {states: [ob]})

for _ in range(n_episodes):

ob = env.reset()

done = False

obs = []

actions = []

rewards = []

returns = []

while not done:

a = act(ob)

new_ob, r, done, info = env.step(a)

obs.append(ob)

actions.append(a)

rewards.append(r)

ob = new_ob

# Estimate returns backwards.

return_so_far = 0.0

for r in rewards[::-1]:

return_so_far = gamma * return_so_far + r

returns.append(return_so_far)

returns = returns[::-1]

# Update the policy network with the data from one episode.

sess.run([optim_pi], feed_dict={

states: np.array(obs),

actions: np.array(actions),

returns: np.array(returns),

})

The full implementation of REINFORCE is here.

Actor-Critic

The actor-critic algorithm learns two models at the same time, the actor for learning the best policy and the critic for estimating the state value.

- Initialize the actor network, $\pi(a \vert s)$ and the critic, $V(s)$

- Collect a new transition (s, a, r, s’): Sample the action $a \sim \pi(a \vert s)$ for the current state s, and get the reward r and the next state s'.

- Compute the TD target during episode rollout, $G_t = r + \gamma V(s’)$ and TD error, $\delta_t = r + \gamma V(s’) - V(s)$.

- Update the critic network by minimizing the critic loss: $L_c = (V(s) - G_t)$.

- Update the actor network by minimizing the actor loss: $L_a = - \delta_t \log \pi(a \vert s)$.

- Set s’ = s and repeat step 2.-5.

Overall the implementation looks pretty similar to REINFORCE with an extra critic network. The full implementation is here.

# Inputs

states = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(None, observation_size), name='state')

actions = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, shape=(None,), name='action')

td_targets = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, shape=(None,), name='td_target')

# Actor: action probabilities

actor = dense_nn(states, [32, 32, env.action_space.n], name='actor')

# Critic: action value (Q-value)

critic = dense_nn(states, [32, 32, 1], name='critic')

action_ohe = tf.one_hot(actions, act_size, 1.0, 0.0, name='action_one_hot')

pred_value = tf.reduce_sum(critic * action_ohe, reduction_indices=-1, name='q_acted')

td_errors = td_targets - tf.reshape(pred_value, [-1])

with tf.variable_scope('critic_train'):

loss_c = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(td_errors))

optim_c = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(0.01).minimize(loss_c)

with tf.variable_scope('actor_train'):

loss_a = tf.reduce_mean(

tf.stop_gradient(td_errors) * tf.nn.sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(

logits=actor, labels=actions),

name='loss_actor')

optim_a = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(0.01).minimize(loss_a)

train_ops = [optim_c, optim_a]

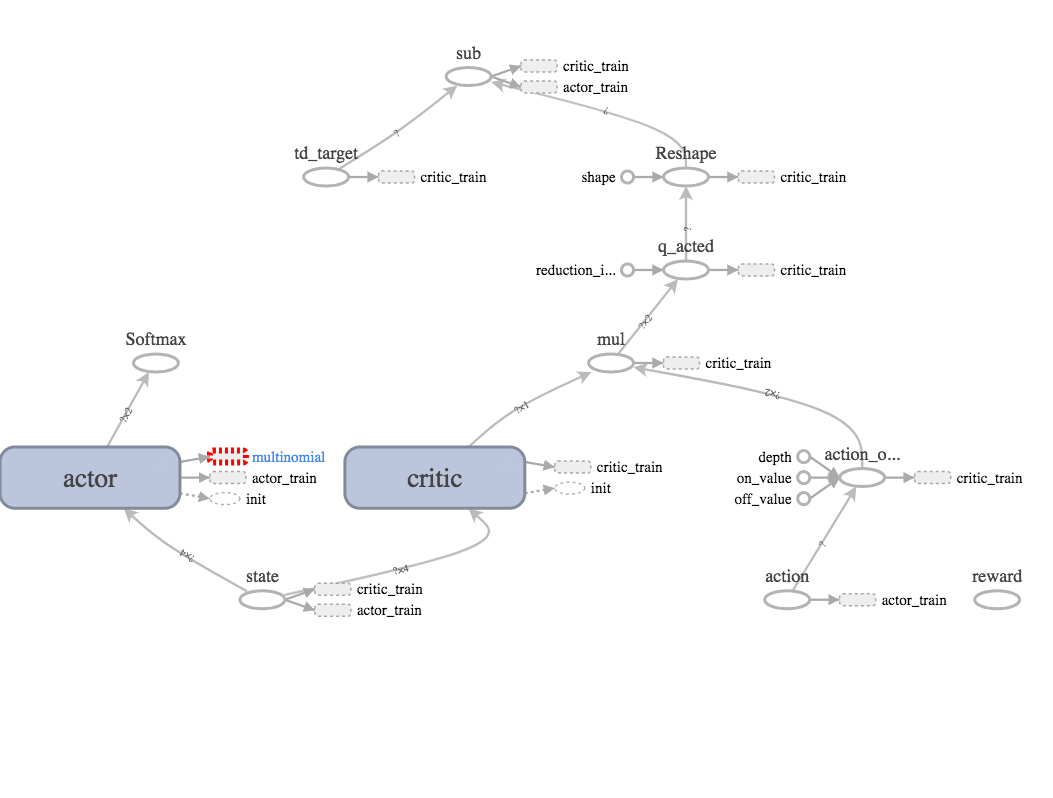

The tensorboard graph is always helpful:

References

[2] Christopher JCH Watkins, and Peter Dayan. “Q-learning.” Machine learning 8.3-4 (1992): 279-292.

[3] Hado Van Hasselt, Arthur Guez, and David Silver. “Deep Reinforcement Learning with Double Q-Learning.” AAAI. Vol. 16. 2016.

[4] Hado van Hasselt. “Double Q-learning.” NIPS, 23:2613–2621, 2010.

[5] Ziyu Wang, et al. Dueling network architectures for deep reinforcement learning. ICML. 2016.