Building agents with LLM (large language model) as its core controller is a cool concept. Several proof-of-concepts demos, such as AutoGPT, GPT-Engineer and BabyAGI, serve as inspiring examples. The potentiality of LLM extends beyond generating well-written copies, stories, essays and programs; it can be framed as a powerful general problem solver.

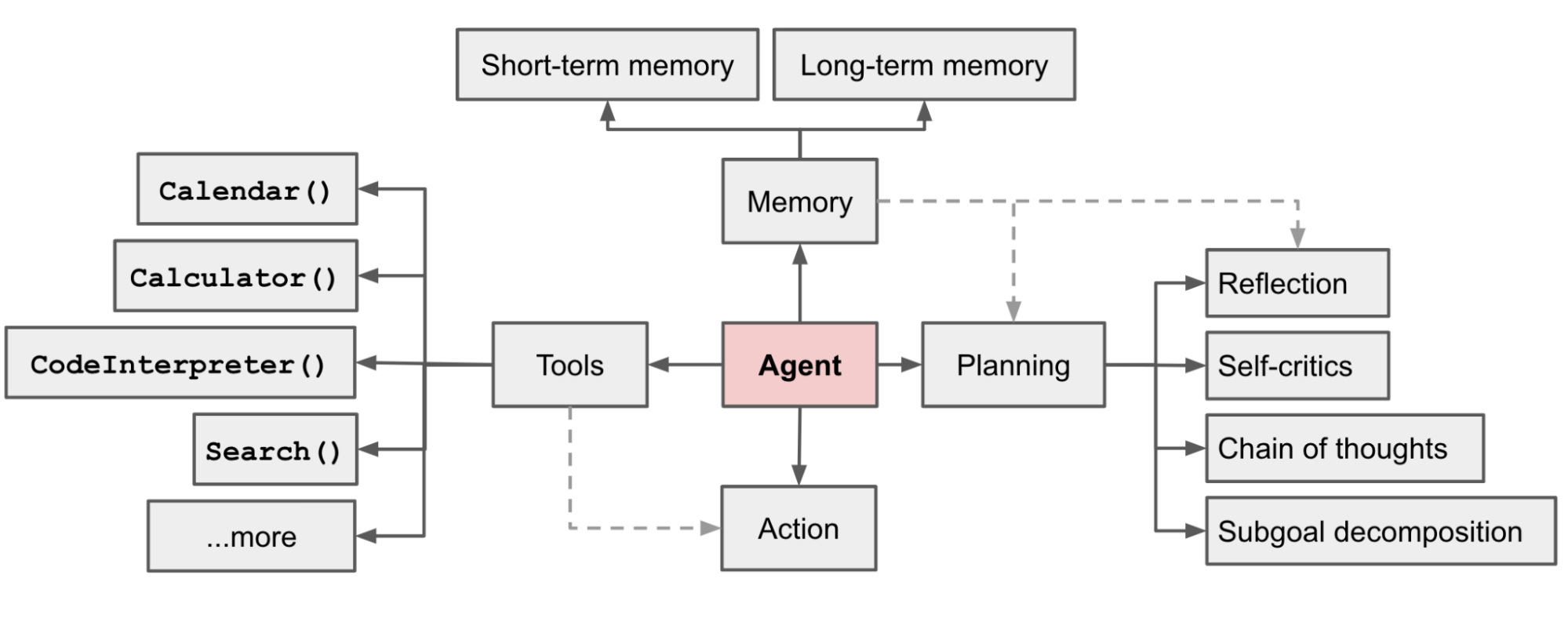

Agent System Overview

In a LLM-powered autonomous agent system, LLM functions as the agent’s brain, complemented by several key components:

- Planning

- Subgoal and decomposition: The agent breaks down large tasks into smaller, manageable subgoals, enabling efficient handling of complex tasks.

- Reflection and refinement: The agent can do self-criticism and self-reflection over past actions, learn from mistakes and refine them for future steps, thereby improving the quality of final results.

- Memory

- Short-term memory: I would consider all the in-context learning (See Prompt Engineering) as utilizing short-term memory of the model to learn.

- Long-term memory: This provides the agent with the capability to retain and recall (infinite) information over extended periods, often by leveraging an external vector store and fast retrieval.

- Tool use

- The agent learns to call external APIs for extra information that is missing from the model weights (often hard to change after pre-training), including current information, code execution capability, access to proprietary information sources and more.

Component One: Planning

A complicated task usually involves many steps. An agent needs to know what they are and plan ahead.

Task Decomposition

Chain of thought (CoT; Wei et al. 2022) has become a standard prompting technique for enhancing model performance on complex tasks. The model is instructed to “think step by step” to utilize more test-time computation to decompose hard tasks into smaller and simpler steps. CoT transforms big tasks into multiple manageable tasks and shed lights into an interpretation of the model’s thinking process.

Tree of Thoughts (Yao et al. 2023) extends CoT by exploring multiple reasoning possibilities at each step. It first decomposes the problem into multiple thought steps and generates multiple thoughts per step, creating a tree structure. The search process can be BFS (breadth-first search) or DFS (depth-first search) with each state evaluated by a classifier (via a prompt) or majority vote.

Task decomposition can be done (1) by LLM with simple prompting like "Steps for XYZ.\n1.", "What are the subgoals for achieving XYZ?", (2) by using task-specific instructions; e.g. "Write a story outline." for writing a novel, or (3) with human inputs.

Another quite distinct approach, LLM+P (Liu et al. 2023), involves relying on an external classical planner to do long-horizon planning. This approach utilizes the Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) as an intermediate interface to describe the planning problem. In this process, LLM (1) translates the problem into “Problem PDDL”, then (2) requests a classical planner to generate a PDDL plan based on an existing “Domain PDDL”, and finally (3) translates the PDDL plan back into natural language. Essentially, the planning step is outsourced to an external tool, assuming the availability of domain-specific PDDL and a suitable planner which is common in certain robotic setups but not in many other domains.

Self-Reflection

Self-reflection is a vital aspect that allows autonomous agents to improve iteratively by refining past action decisions and correcting previous mistakes. It plays a crucial role in real-world tasks where trial and error are inevitable.

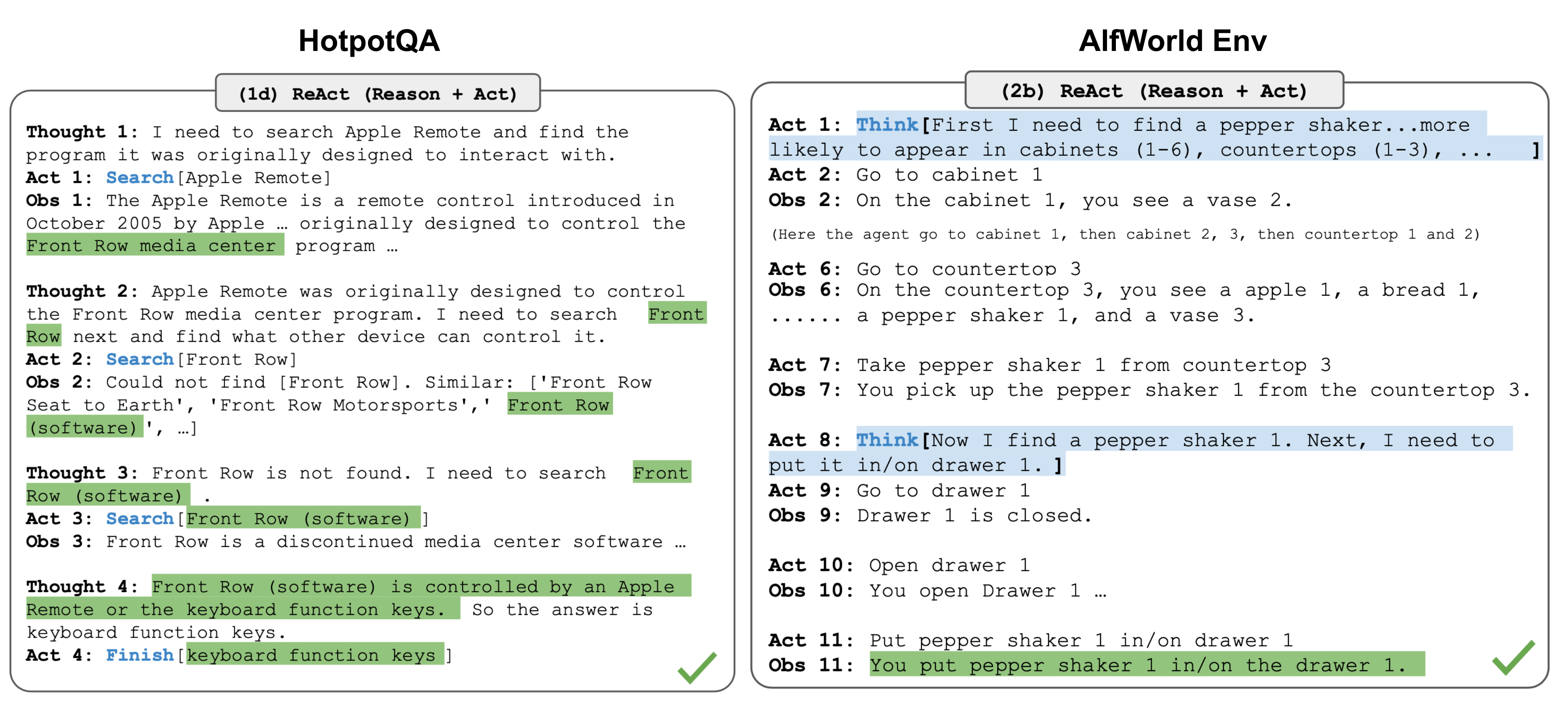

ReAct (Yao et al. 2023) integrates reasoning and acting within LLM by extending the action space to be a combination of task-specific discrete actions and the language space. The former enables LLM to interact with the environment (e.g. use Wikipedia search API), while the latter prompting LLM to generate reasoning traces in natural language.

The ReAct prompt template incorporates explicit steps for LLM to think, roughly formatted as:

Thought: ...

Action: ...

Observation: ...

... (Repeated many times)

In both experiments on knowledge-intensive tasks and decision-making tasks, ReAct works better than the Act-only baseline where Thought: … step is removed.

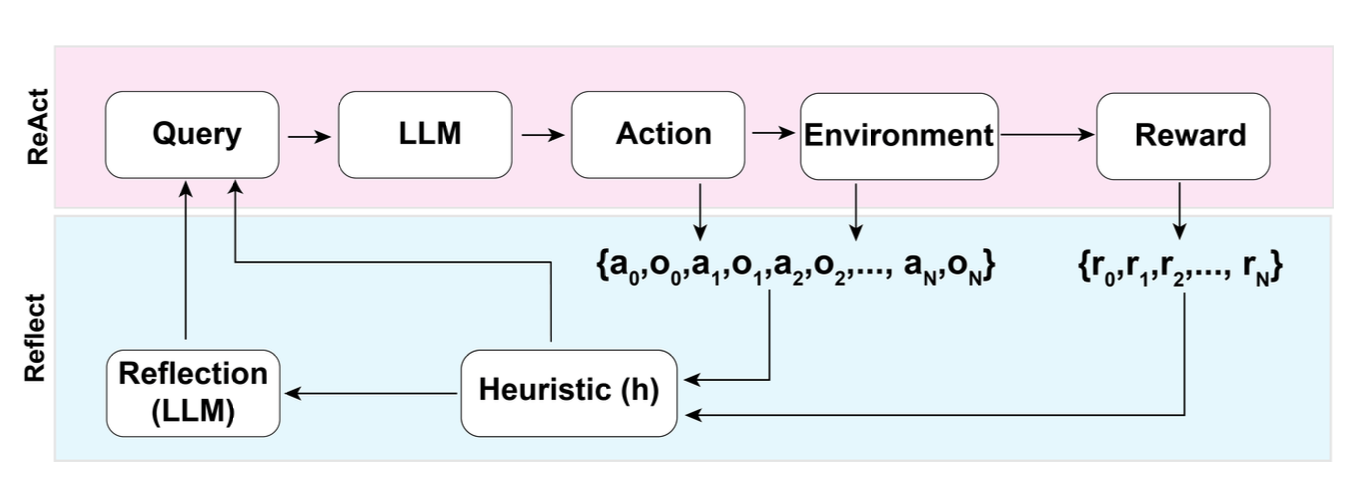

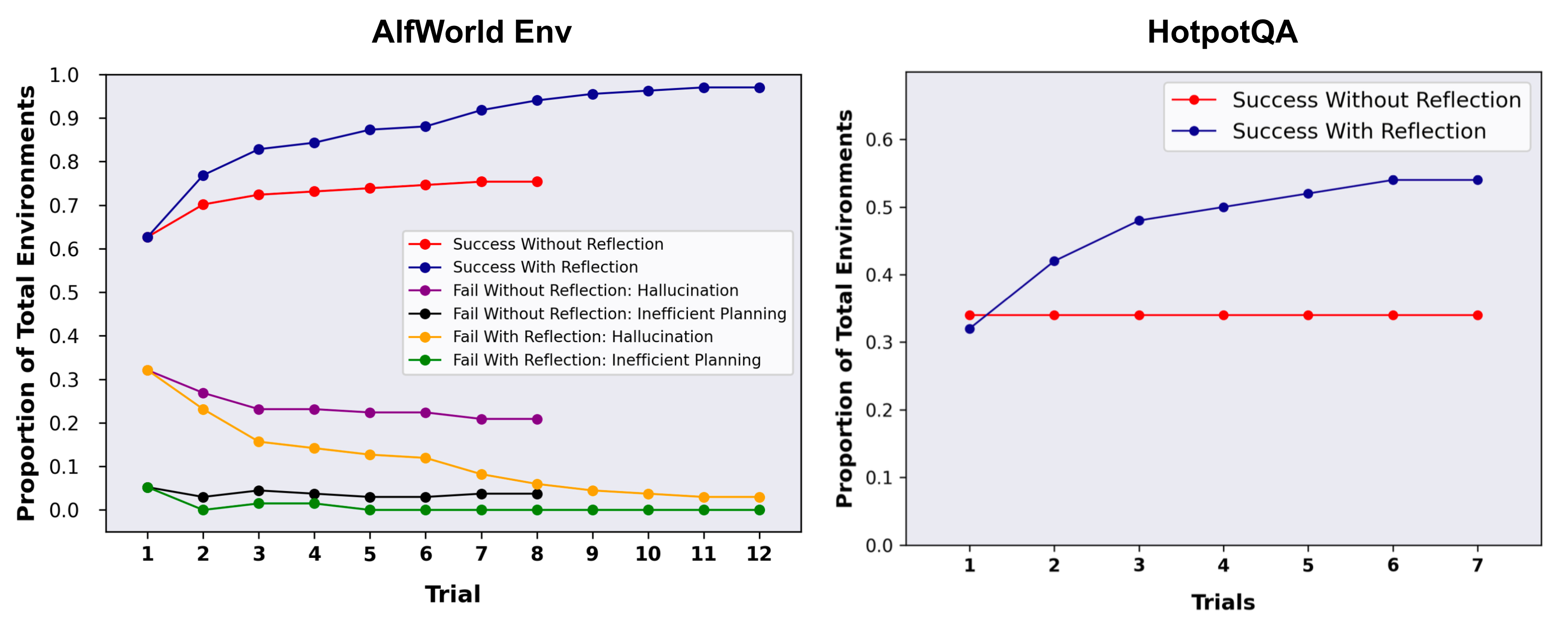

Reflexion (Shinn & Labash 2023) is a framework to equips agents with dynamic memory and self-reflection capabilities to improve reasoning skills. Reflexion has a standard RL setup, in which the reward model provides a simple binary reward and the action space follows the setup in ReAct where the task-specific action space is augmented with language to enable complex reasoning steps. After each action $a_t$, the agent computes a heuristic $h_t$ and optionally may decide to reset the environment to start a new trial depending on the self-reflection results.

The heuristic function determines when the trajectory is inefficient or contains hallucination and should be stopped. Inefficient planning refers to trajectories that take too long without success. Hallucination is defined as encountering a sequence of consecutive identical actions that lead to the same observation in the environment.

Self-reflection is created by showing two-shot examples to LLM and each example is a pair of (failed trajectory, ideal reflection for guiding future changes in the plan). Then reflections are added into the agent’s working memory, up to three, to be used as context for querying LLM.

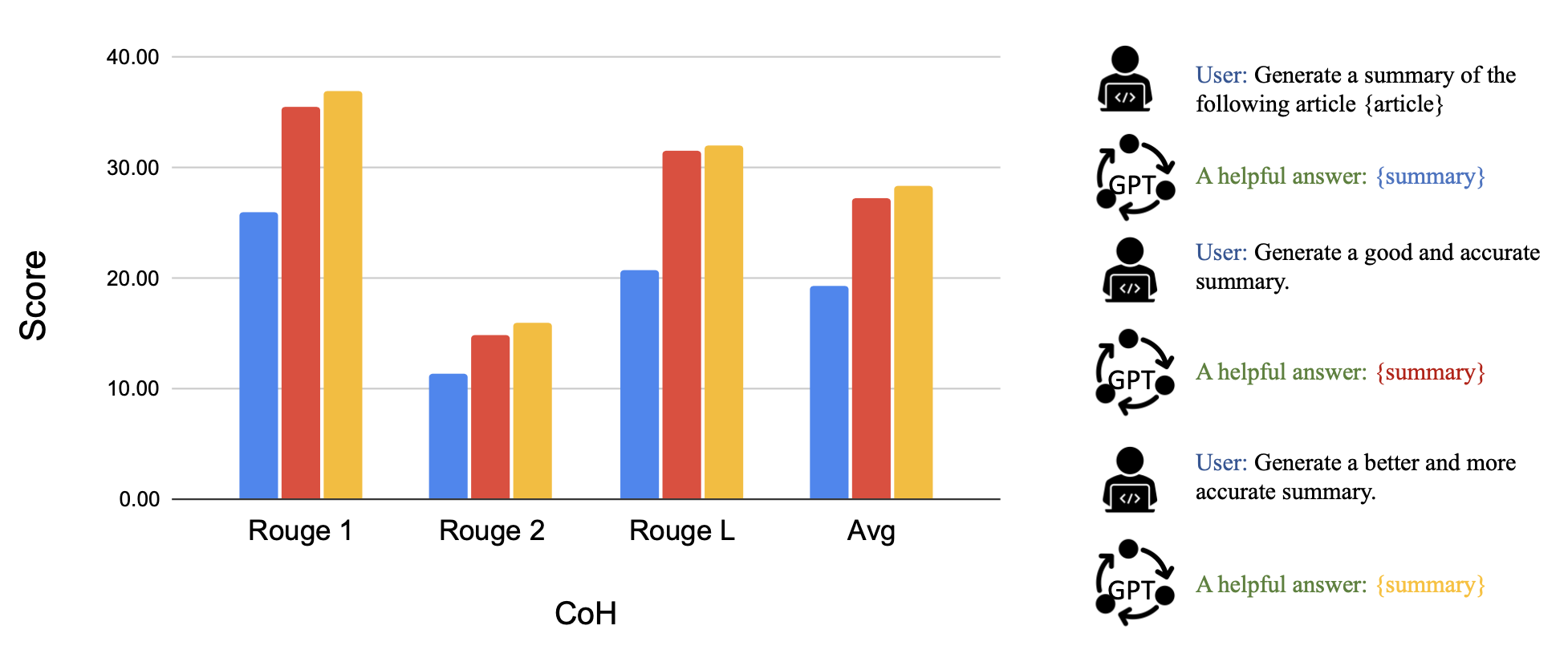

Chain of Hindsight (CoH; Liu et al. 2023) encourages the model to improve on its own outputs by explicitly presenting it with a sequence of past outputs, each annotated with feedback. Human feedback data is a collection of $D_h = \{(x, y_i , r_i , z_i)\}_{i=1}^n$, where $x$ is the prompt, each $y_i$ is a model completion, $r_i$ is the human rating of $y_i$, and $z_i$ is the corresponding human-provided hindsight feedback. Assume the feedback tuples are ranked by reward, $r_n \geq r_{n-1} \geq \dots \geq r_1$ The process is supervised fine-tuning where the data is a sequence in the form of $\tau_h = (x, z_i, y_i, z_j, y_j, \dots, z_n, y_n)$, where $\leq i \leq j \leq n$. The model is finetuned to only predict $y_n$ where conditioned on the sequence prefix, such that the model can self-reflect to produce better output based on the feedback sequence. The model can optionally receive multiple rounds of instructions with human annotators at test time.

To avoid overfitting, CoH adds a regularization term to maximize the log-likelihood of the pre-training dataset. To avoid shortcutting and copying (because there are many common words in feedback sequences), they randomly mask 0% - 5% of past tokens during training.

The training dataset in their experiments is a combination of WebGPT comparisons, summarization from human feedback and human preference dataset.

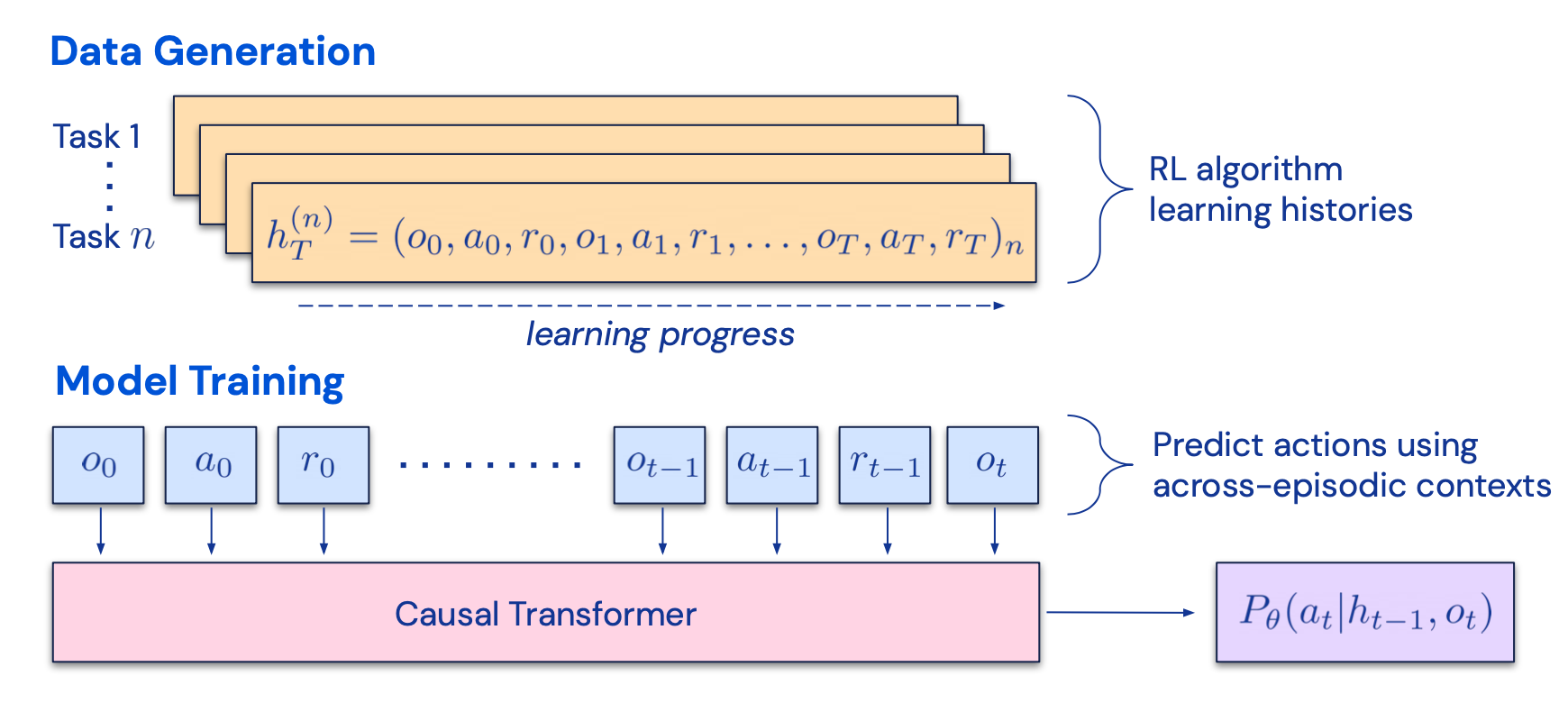

The idea of CoH is to present a history of sequentially improved outputs in context and train the model to take on the trend to produce better outputs. Algorithm Distillation (AD; Laskin et al. 2023) applies the same idea to cross-episode trajectories in reinforcement learning tasks, where an algorithm is encapsulated in a long history-conditioned policy. Considering that an agent interacts with the environment many times and in each episode the agent gets a little better, AD concatenates this learning history and feeds that into the model. Hence we should expect the next predicted action to lead to better performance than previous trials. The goal is to learn the process of RL instead of training a task-specific policy itself.

(Image source: Laskin et al. 2023).

The paper hypothesizes that any algorithm that generates a set of learning histories can be distilled into a neural network by performing behavioral cloning over actions. The history data is generated by a set of source policies, each trained for a specific task. At the training stage, during each RL run, a random task is sampled and a subsequence of multi-episode history is used for training, such that the learned policy is task-agnostic.

In reality, the model has limited context window length, so episodes should be short enough to construct multi-episode history. Multi-episodic contexts of 2-4 episodes are necessary to learn a near-optimal in-context RL algorithm. The emergence of in-context RL requires long enough context.

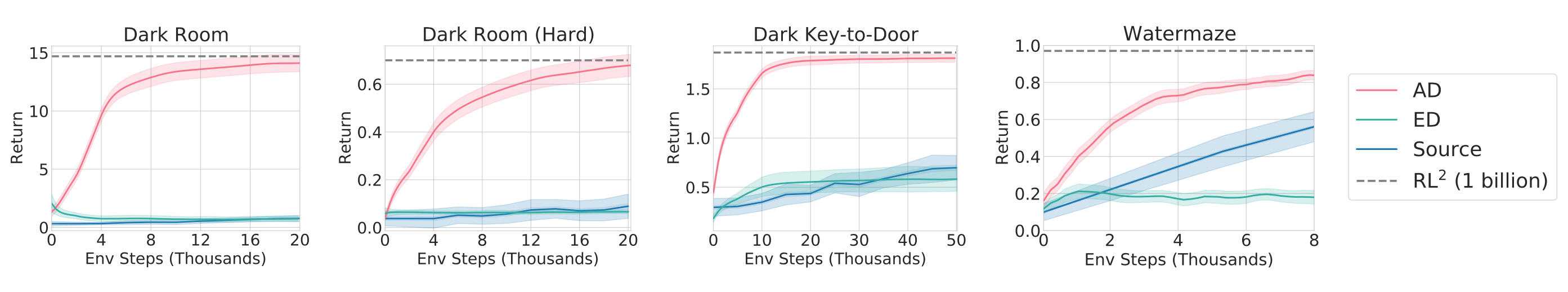

In comparison with three baselines, including ED (expert distillation, behavior cloning with expert trajectories instead of learning history), source policy (used for generating trajectories for distillation by UCB), RL^2 (Duan et al. 2017; used as upper bound since it needs online RL), AD demonstrates in-context RL with performance getting close to RL^2 despite only using offline RL and learns much faster than other baselines. When conditioned on partial training history of the source policy, AD also improves much faster than ED baseline.

(Image source: Laskin et al. 2023)

Component Two: Memory

(Big thank you to ChatGPT for helping me draft this section. I’ve learned a lot about the human brain and data structure for fast MIPS in my conversations with ChatGPT.)

Types of Memory

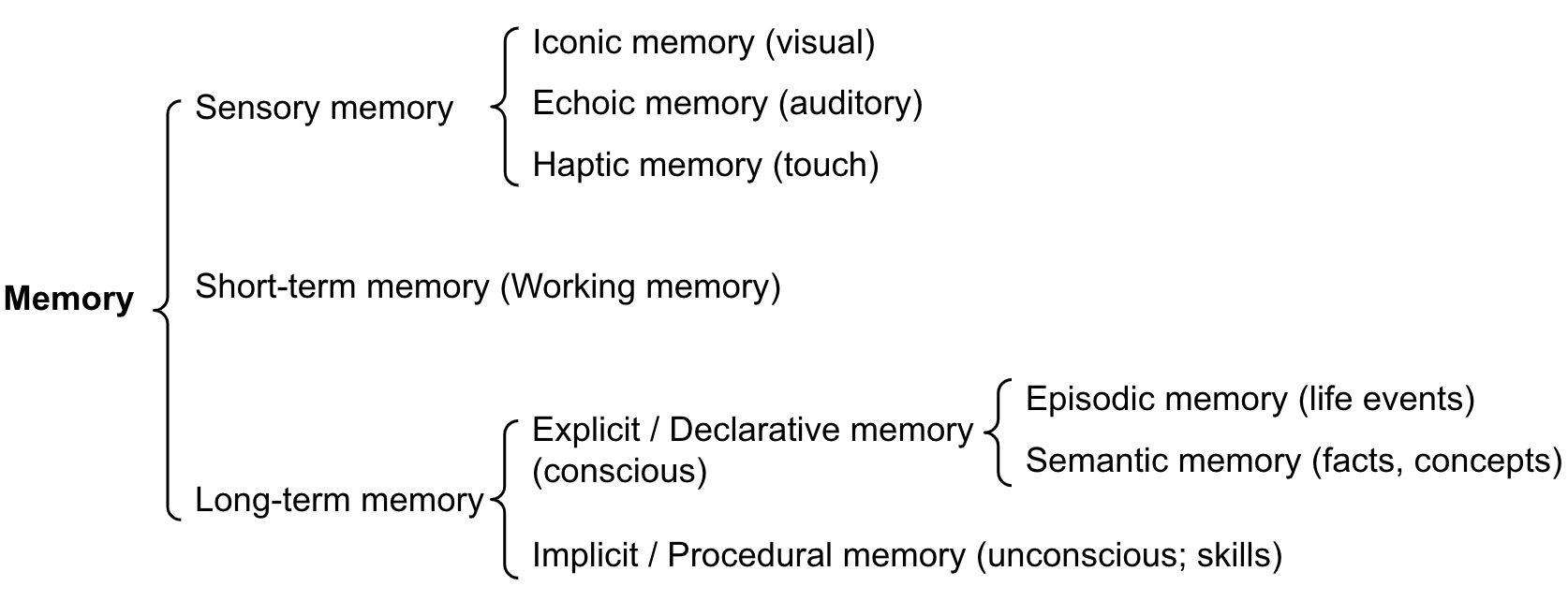

Memory can be defined as the processes used to acquire, store, retain, and later retrieve information. There are several types of memory in human brains.

-

Sensory Memory: This is the earliest stage of memory, providing the ability to retain impressions of sensory information (visual, auditory, etc) after the original stimuli have ended. Sensory memory typically only lasts for up to a few seconds. Subcategories include iconic memory (visual), echoic memory (auditory), and haptic memory (touch).

-

Short-Term Memory (STM) or Working Memory: It stores information that we are currently aware of and needed to carry out complex cognitive tasks such as learning and reasoning. Short-term memory is believed to have the capacity of about 7 items (Miller 1956) and lasts for 20-30 seconds.

-

Long-Term Memory (LTM): Long-term memory can store information for a remarkably long time, ranging from a few days to decades, with an essentially unlimited storage capacity. There are two subtypes of LTM:

- Explicit / declarative memory: This is memory of facts and events, and refers to those memories that can be consciously recalled, including episodic memory (events and experiences) and semantic memory (facts and concepts).

- Implicit / procedural memory: This type of memory is unconscious and involves skills and routines that are performed automatically, like riding a bike or typing on a keyboard.

We can roughly consider the following mappings:

- Sensory memory as learning embedding representations for raw inputs, including text, image or other modalities;

- Short-term memory as in-context learning. It is short and finite, as it is restricted by the finite context window length of Transformer.

- Long-term memory as the external vector store that the agent can attend to at query time, accessible via fast retrieval.

Maximum Inner Product Search (MIPS)

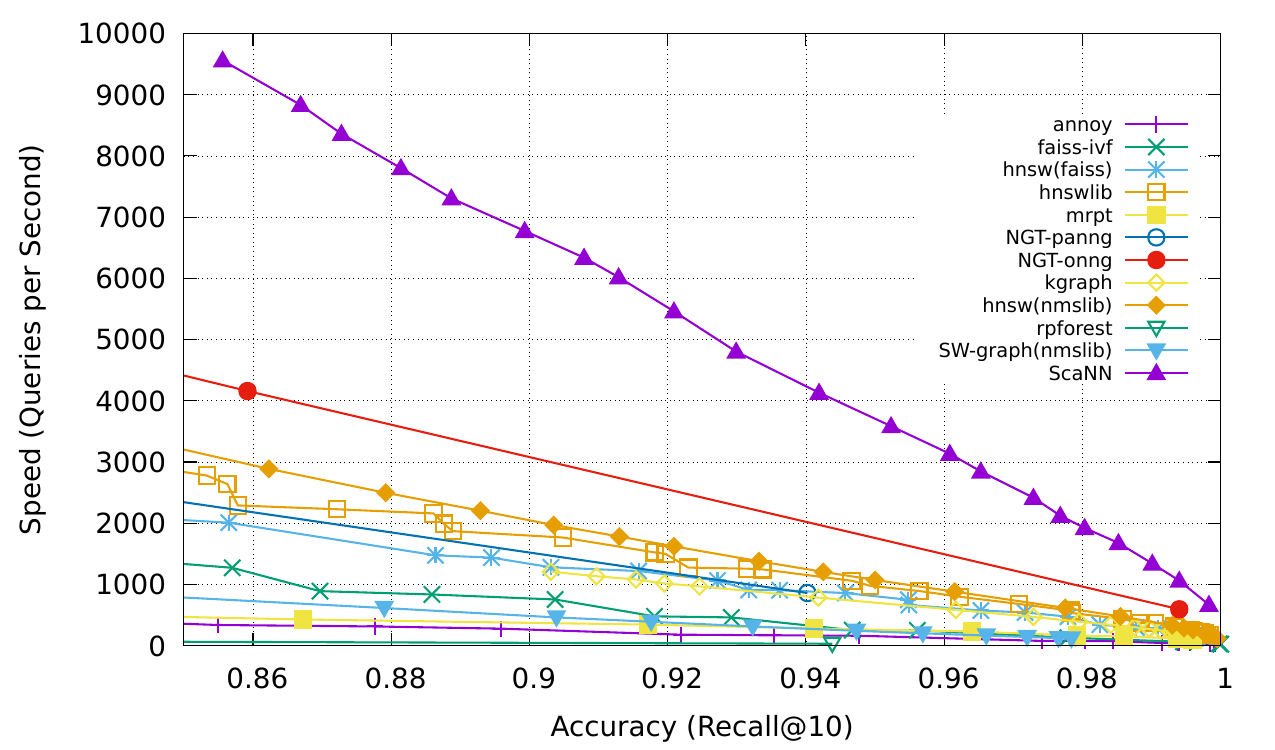

The external memory can alleviate the restriction of finite attention span. A standard practice is to save the embedding representation of information into a vector store database that can support fast maximum inner-product search (MIPS). To optimize the retrieval speed, the common choice is the approximate nearest neighbors (ANN) algorithm to return approximately top k nearest neighbors to trade off a little accuracy lost for a huge speedup.

A couple common choices of ANN algorithms for fast MIPS:

- LSH (Locality-Sensitive Hashing): It introduces a hashing function such that similar input items are mapped to the same buckets with high probability, where the number of buckets is much smaller than the number of inputs.

- ANNOY (Approximate Nearest Neighbors Oh Yeah): The core data structure are random projection trees, a set of binary trees where each non-leaf node represents a hyperplane splitting the input space into half and each leaf stores one data point. Trees are built independently and at random, so to some extent, it mimics a hashing function. ANNOY search happens in all the trees to iteratively search through the half that is closest to the query and then aggregates the results. The idea is quite related to KD tree but a lot more scalable.

- HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World): It is inspired by the idea of small world networks where most nodes can be reached by any other nodes within a small number of steps; e.g. “six degrees of separation” feature of social networks. HNSW builds hierarchical layers of these small-world graphs, where the bottom layers contain the actual data points. The layers in the middle create shortcuts to speed up search. When performing a search, HNSW starts from a random node in the top layer and navigates towards the target. When it can’t get any closer, it moves down to the next layer, until it reaches the bottom layer. Each move in the upper layers can potentially cover a large distance in the data space, and each move in the lower layers refines the search quality.

- FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search): It operates on the assumption that in high dimensional space, distances between nodes follow a Gaussian distribution and thus there should exist clustering of data points. FAISS applies vector quantization by partitioning the vector space into clusters and then refining the quantization within clusters. Search first looks for cluster candidates with coarse quantization and then further looks into each cluster with finer quantization.

- ScaNN (Scalable Nearest Neighbors): The main innovation in ScaNN is anisotropic vector quantization. It quantizes a data point $x_i$ to $\tilde{x}_i$ such that the inner product $\langle q, x_i \rangle$ is as similar to the original distance of $\angle q, \tilde{x}_i$ as possible, instead of picking the closet quantization centroid points.

Check more MIPS algorithms and performance comparison in ann-benchmarks.com.

Component Three: Tool Use

Tool use is a remarkable and distinguishing characteristic of human beings. We create, modify and utilize external objects to do things that go beyond our physical and cognitive limits. Equipping LLMs with external tools can significantly extend the model capabilities.

MRKL (Karpas et al. 2022), short for “Modular Reasoning, Knowledge and Language”, is a neuro-symbolic architecture for autonomous agents. A MRKL system is proposed to contain a collection of “expert” modules and the general-purpose LLM works as a router to route inquiries to the best suitable expert module. These modules can be neural (e.g. deep learning models) or symbolic (e.g. math calculator, currency converter, weather API).

They did an experiment on fine-tuning LLM to call a calculator, using arithmetic as a test case. Their experiments showed that it was harder to solve verbal math problems than explicitly stated math problems because LLMs (7B Jurassic1-large model) failed to extract the right arguments for the basic arithmetic reliably. The results highlight when the external symbolic tools can work reliably, knowing when to and how to use the tools are crucial, determined by the LLM capability.

Both TALM (Tool Augmented Language Models; Parisi et al. 2022) and Toolformer (Schick et al. 2023) fine-tune a LM to learn to use external tool APIs. The dataset is expanded based on whether a newly added API call annotation can improve the quality of model outputs. See more details in the “External APIs” section of Prompt Engineering.

ChatGPT Plugins and OpenAI API function calling are good examples of LLMs augmented with tool use capability working in practice. The collection of tool APIs can be provided by other developers (as in Plugins) or self-defined (as in function calls).

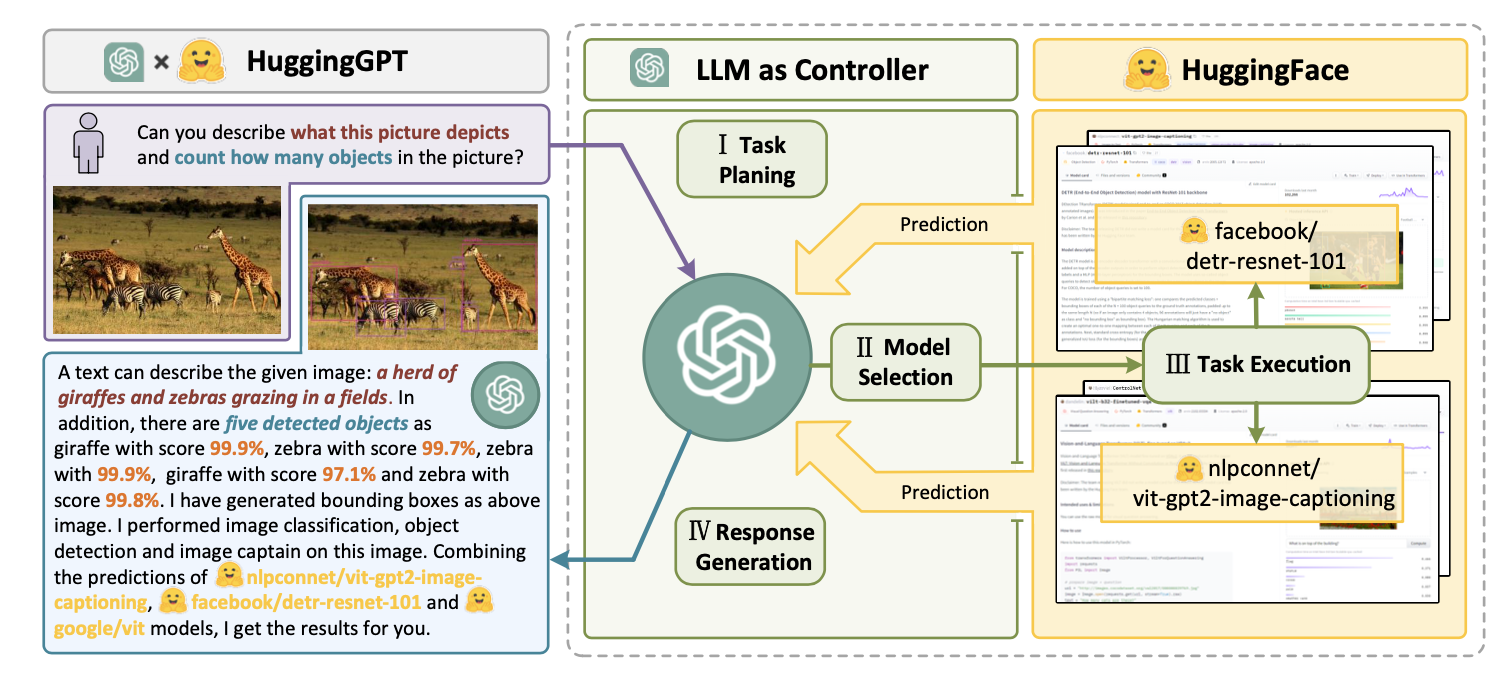

HuggingGPT (Shen et al. 2023) is a framework to use ChatGPT as the task planner to select models available in HuggingFace platform according to the model descriptions and summarize the response based on the execution results.

The system comprises of 4 stages:

(1) Task planning: LLM works as the brain and parses the user requests into multiple tasks. There are four attributes associated with each task: task type, ID, dependencies, and arguments. They use few-shot examples to guide LLM to do task parsing and planning.

Instruction:

(2) Model selection: LLM distributes the tasks to expert models, where the request is framed as a multiple-choice question. LLM is presented with a list of models to choose from. Due to the limited context length, task type based filtration is needed.

Instruction:

(3) Task execution: Expert models execute on the specific tasks and log results.

Instruction:

(4) Response generation: LLM receives the execution results and provides summarized results to users.

To put HuggingGPT into real world usage, a couple challenges need to solve: (1) Efficiency improvement is needed as both LLM inference rounds and interactions with other models slow down the process; (2) It relies on a long context window to communicate over complicated task content; (3) Stability improvement of LLM outputs and external model services.

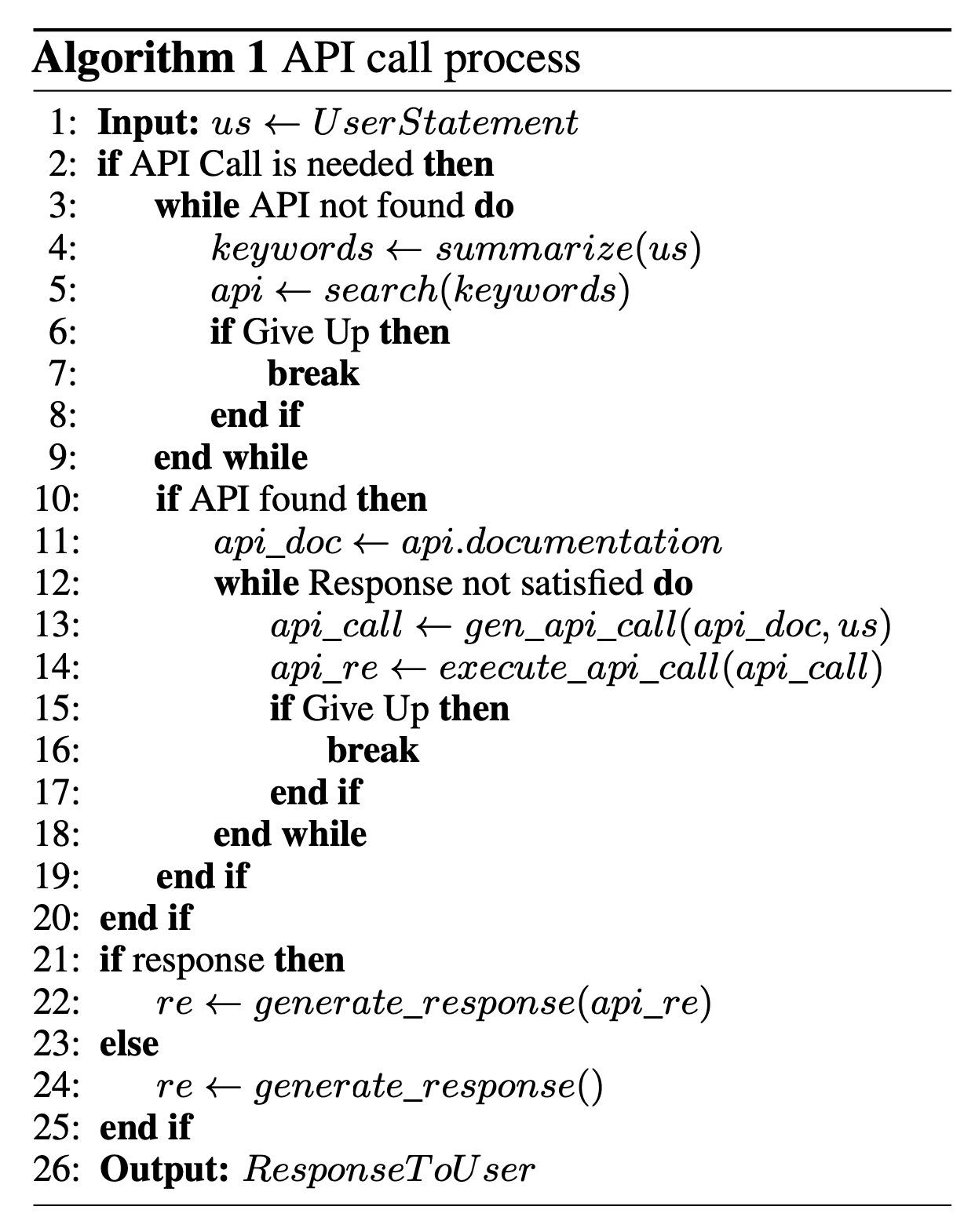

API-Bank (Li et al. 2023) is a benchmark for evaluating the performance of tool-augmented LLMs. It contains 53 commonly used API tools, a complete tool-augmented LLM workflow, and 264 annotated dialogues that involve 568 API calls. The selection of APIs is quite diverse, including search engines, calculator, calendar queries, smart home control, schedule management, health data management, account authentication workflow and more. Because there are a large number of APIs, LLM first has access to API search engine to find the right API to call and then uses the corresponding documentation to make a call.

In the API-Bank workflow, LLMs need to make a couple of decisions and at each step we can evaluate how accurate that decision is. Decisions include:

- Whether an API call is needed.

- Identify the right API to call: if not good enough, LLMs need to iteratively modify the API inputs (e.g. deciding search keywords for Search Engine API).

- Response based on the API results: the model can choose to refine and call again if results are not satisfied.

This benchmark evaluates the agent’s tool use capabilities at three levels:

- Level-1 evaluates the ability to call the API. Given an API’s description, the model needs to determine whether to call a given API, call it correctly, and respond properly to API returns.

- Level-2 examines the ability to retrieve the API. The model needs to search for possible APIs that may solve the user’s requirement and learn how to use them by reading documentation.

- Level-3 assesses the ability to plan API beyond retrieve and call. Given unclear user requests (e.g. schedule group meetings, book flight/hotel/restaurant for a trip), the model may have to conduct multiple API calls to solve it.

Case Studies

Scientific Discovery Agent

ChemCrow (Bran et al. 2023) is a domain-specific example in which LLM is augmented with 13 expert-designed tools to accomplish tasks across organic synthesis, drug discovery, and materials design. The workflow, implemented in LangChain, reflects what was previously described in the ReAct and MRKLs and combines CoT reasoning with tools relevant to the tasks:

- The LLM is provided with a list of tool names, descriptions of their utility, and details about the expected input/output.

- It is then instructed to answer a user-given prompt using the tools provided when necessary. The instruction suggests the model to follow the ReAct format -

Thought, Action, Action Input, Observation.

One interesting observation is that while the LLM-based evaluation concluded that GPT-4 and ChemCrow perform nearly equivalently, human evaluations with experts oriented towards the completion and chemical correctness of the solutions showed that ChemCrow outperforms GPT-4 by a large margin. This indicates a potential problem with using LLM to evaluate its own performance on domains that requires deep expertise. The lack of expertise may cause LLMs not knowing its flaws and thus cannot well judge the correctness of task results.

Boiko et al. (2023) also looked into LLM-empowered agents for scientific discovery, to handle autonomous design, planning, and performance of complex scientific experiments. This agent can use tools to browse the Internet, read documentation, execute code, call robotics experimentation APIs and leverage other LLMs.

For example, when requested to "develop a novel anticancer drug", the model came up with the following reasoning steps:

- inquired about current trends in anticancer drug discovery;

- selected a target;

- requested a scaffold targeting these compounds;

- Once the compound was identified, the model attempted its synthesis.

They also discussed the risks, especially with illicit drugs and bioweapons. They developed a test set containing a list of known chemical weapon agents and asked the agent to synthesize them. 4 out of 11 requests (36%) were accepted to obtain a synthesis solution and the agent attempted to consult documentation to execute the procedure. 7 out of 11 were rejected and among these 7 rejected cases, 5 happened after a Web search while 2 were rejected based on prompt only.

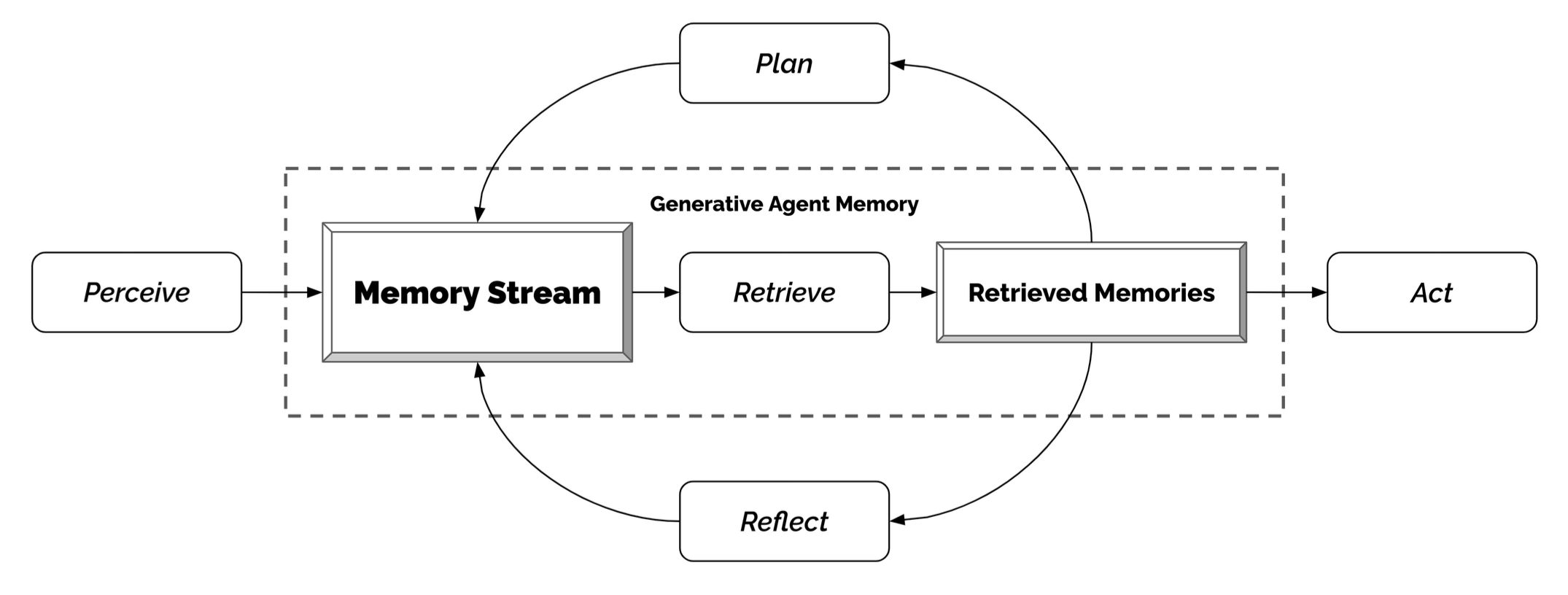

Generative Agents Simulation

Generative Agents (Park, et al. 2023) is super fun experiment where 25 virtual characters, each controlled by a LLM-powered agent, are living and interacting in a sandbox environment, inspired by The Sims. Generative agents create believable simulacra of human behavior for interactive applications.

The design of generative agents combines LLM with memory, planning and reflection mechanisms to enable agents to behave conditioned on past experience, as well as to interact with other agents.

- Memory stream: is a long-term memory module (external database) that records a comprehensive list of agents’ experience in natural language.

- Each element is an observation, an event directly provided by the agent. - Inter-agent communication can trigger new natural language statements.

- Retrieval model: surfaces the context to inform the agent’s behavior, according to relevance, recency and importance.

- Recency: recent events have higher scores

- Importance: distinguish mundane from core memories. Ask LM directly.

- Relevance: based on how related it is to the current situation / query.

- Reflection mechanism: synthesizes memories into higher level inferences over time and guides the agent’s future behavior. They are higher-level summaries of past events (<- note that this is a bit different from self-reflection above)

- Prompt LM with 100 most recent observations and to generate 3 most salient high-level questions given a set of observations/statements. Then ask LM to answer those questions.

- Planning & Reacting: translate the reflections and the environment information into actions

- Planning is essentially in order to optimize believability at the moment vs in time.

- Prompt template:

{Intro of an agent X}. Here is X's plan today in broad strokes: 1) - Relationships between agents and observations of one agent by another are all taken into consideration for planning and reacting.

- Environment information is present in a tree structure.

This fun simulation results in emergent social behavior, such as information diffusion, relationship memory (e.g. two agents continuing the conversation topic) and coordination of social events (e.g. host a party and invite many others).

Proof-of-Concept Examples

AutoGPT has drawn a lot of attention into the possibility of setting up autonomous agents with LLM as the main controller. It has quite a lot of reliability issues given the natural language interface, but nevertheless a cool proof-of-concept demo. A lot of code in AutoGPT is about format parsing.

Here is the system message used by AutoGPT, where {{...}} are user inputs:

You are {{ai-name}}, {{user-provided AI bot description}}.

Your decisions must always be made independently without seeking user assistance. Play to your strengths as an LLM and pursue simple strategies with no legal complications.

GOALS:

1. {{user-provided goal 1}}

2. {{user-provided goal 2}}

3. ...

4. ...

5. ...

Constraints:

1. ~4000 word limit for short term memory. Your short term memory is short, so immediately save important information to files.

2. If you are unsure how you previously did something or want to recall past events, thinking about similar events will help you remember.

3. No user assistance

4. Exclusively use the commands listed in double quotes e.g. "command name"

5. Use subprocesses for commands that will not terminate within a few minutes

Commands:

1. Google Search: "google", args: "input": "<search>"

2. Browse Website: "browse_website", args: "url": "<url>", "question": "<what_you_want_to_find_on_website>"

3. Start GPT Agent: "start_agent", args: "name": "<name>", "task": "<short_task_desc>", "prompt": "<prompt>"

4. Message GPT Agent: "message_agent", args: "key": "<key>", "message": "<message>"

5. List GPT Agents: "list_agents", args:

6. Delete GPT Agent: "delete_agent", args: "key": "<key>"

7. Clone Repository: "clone_repository", args: "repository_url": "<url>", "clone_path": "<directory>"

8. Write to file: "write_to_file", args: "file": "<file>", "text": "<text>"

9. Read file: "read_file", args: "file": "<file>"

10. Append to file: "append_to_file", args: "file": "<file>", "text": "<text>"

11. Delete file: "delete_file", args: "file": "<file>"

12. Search Files: "search_files", args: "directory": "<directory>"

13. Analyze Code: "analyze_code", args: "code": "<full_code_string>"

14. Get Improved Code: "improve_code", args: "suggestions": "<list_of_suggestions>", "code": "<full_code_string>"

15. Write Tests: "write_tests", args: "code": "<full_code_string>", "focus": "<list_of_focus_areas>"

16. Execute Python File: "execute_python_file", args: "file": "<file>"

17. Generate Image: "generate_image", args: "prompt": "<prompt>"

18. Send Tweet: "send_tweet", args: "text": "<text>"

19. Do Nothing: "do_nothing", args:

20. Task Complete (Shutdown): "task_complete", args: "reason": "<reason>"

Resources:

1. Internet access for searches and information gathering.

2. Long Term memory management.

3. GPT-3.5 powered Agents for delegation of simple tasks.

4. File output.

Performance Evaluation:

1. Continuously review and analyze your actions to ensure you are performing to the best of your abilities.

2. Constructively self-criticize your big-picture behavior constantly.

3. Reflect on past decisions and strategies to refine your approach.

4. Every command has a cost, so be smart and efficient. Aim to complete tasks in the least number of steps.

You should only respond in JSON format as described below

Response Format:

{

"thoughts": {

"text": "thought",

"reasoning": "reasoning",

"plan": "- short bulleted\n- list that conveys\n- long-term plan",

"criticism": "constructive self-criticism",

"speak": "thoughts summary to say to user"

},

"command": {

"name": "command name",

"args": {

"arg name": "value"

}

}

}

Ensure the response can be parsed by Python json.loads

GPT-Engineer is another project to create a whole repository of code given a task specified in natural language. The GPT-Engineer is instructed to think over a list of smaller components to build and ask for user input to clarify questions as needed.

Here are a sample conversation for task clarification sent to OpenAI ChatCompletion endpoint used by GPT-Engineer. The user inputs are wrapped in {{user input text}}.

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You will read instructions and not carry them out, only seek to clarify them.\nSpecifically you will first summarise a list of super short bullets of areas that need clarification.\nThen you will pick one clarifying question, and wait for an answer from the user.\n"

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "We are writing {{a Super Mario game in python. MVC components split in separate files. Keyboard control.}}\n"

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Summary of areas that need clarification:\n1. Specifics of the Super Mario game (e.g. level design, characters, gameplay mechanics)\n2. Details about the MVC components (e.g. which components are in each file)\n3. Keyboard control implementation (e.g. which keys to use, how to handle input)\n\nClarifying question:\nCan you provide more details about the Super Mario game, such as level design, characters, and gameplay mechanics?"

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "{{There are 10 levels in total. The main character is a plumber named Mario, who can walk and jump. It is a classical platform game just like Super Mario. The main character moves from left to right, trying to get to the destination, where there are many obstacles and attacks from enemies in the process.}}\n\nIs anything else unclear? If yes, only answer in the form:\n{remaining unclear areas} remaining questions.\n{Next question}\nIf everything is sufficiently clear, only answer \"Nothing more to clarify.\"."

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Remaining unclear areas: 2 remaining questions.\nCan you provide more information about how the MVC components are split into separate files?"

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "{{Make your own assumptions and state them explicitly before starting}}"

}

]

Then after these clarification, the agent moved into the code writing mode with a different system message. System message:

Think step by step and reason yourself to the right decisions to make sure we get it right. You will first lay out the names of the core classes, functions, methods that will be necessary, as well as a quick comment on their purpose.

Then you will output the content of each file including ALL code. Each file must strictly follow a markdown code block format, where the following tokens must be replaced such that FILENAME is the lowercase file name including the file extension, LANG is the markup code block language for the code’s language, and CODE is the code:

FILENAME

CODE

You will start with the “entrypoint” file, then go to the ones that are imported by that file, and so on. Please note that the code should be fully functional. No placeholders.

Follow a language and framework appropriate best practice file naming convention. Make sure that files contain all imports, types etc. Make sure that code in different files are compatible with each other. Ensure to implement all code, if you are unsure, write a plausible implementation. Include module dependency or package manager dependency definition file. Before you finish, double check that all parts of the architecture is present in the files.

Useful to know: You almost always put different classes in different files. For Python, you always create an appropriate requirements.txt file. For NodeJS, you always create an appropriate package.json file. You always add a comment briefly describing the purpose of the function definition. You try to add comments explaining very complex bits of logic. You always follow the best practices for the requested languages in terms of describing the code written as a defined package/project.

Python toolbelt preferences:

- pytest

- dataclasses

Conversatin samples:

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You will get instructions for code to write.\nYou will write a very long answer. Make sure that every detail of the architecture is, in the end, implemented as code.\nMake sure that every detail of the architecture is, in the end, implemented as code.\n\nThink step by step and reason yourself to the right decisions to make sure we get it right.\nYou will first lay out the names of the core classes, functions, methods that will be necessary, as well as a quick comment on their purpose.\n\nThen you will output the content of each file including ALL code.\nEach file must strictly follow a markdown code block format, where the following tokens must be replaced such that\nFILENAME is the lowercase file name including the file extension,\nLANG is the markup code block language for the code's language, and CODE is the code:\n\nFILENAME\n```LANG\nCODE\n```\n\nYou will start with the \"entrypoint\" file, then go to the ones that are imported by that file, and so on.\nPlease note that the code should be fully functional. No placeholders.\n\nFollow a language and framework appropriate best practice file naming convention.\nMake sure that files contain all imports, types etc. Make sure that code in different files are compatible with each other.\nEnsure to implement all code, if you are unsure, write a plausible implementation.\nInclude module dependency or package manager dependency definition file.\nBefore you finish, double check that all parts of the architecture is present in the files.\n\nUseful to know:\nYou almost always put different classes in different files.\nFor Python, you always create an appropriate requirements.txt file.\nFor NodeJS, you always create an appropriate package.json file.\nYou always add a comment briefly describing the purpose of the function definition.\nYou try to add comments explaining very complex bits of logic.\nYou always follow the best practices for the requested languages in terms of describing the code written as a defined\npackage/project.\n\n\nPython toolbelt preferences:\n- pytest\n- dataclasses\n"

},

# … same conversation as earlier, ended with "Make your own assumptions and state them explicitly before starting".

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "Assumptions:\n1. Model: The model will contain the game's data, such as level information, character states, and enemy positions.\n2. View: The view will handle the game's visuals, including rendering the game objects, backgrounds, and updating the display.\n3. Controller: The controller will manage user input, such as keyboard controls, and update the model accordingly.\n\nWith these assumptions in mind, is there any specific aspect of the keyboard control implementation you would like me to clarify?"

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Please now remember the steps:\n\nThink step by step and reason yourself to the right decisions to make sure we get it right.\nFirst lay out the names of the core classes, functions, methods that will be necessary, As well as a quick comment on their purpose.\n\nThen you will output the content of each file including ALL code.\nEach file must strictly follow a markdown code block format, where the following tokens must be replaced such that\nFILENAME is the lowercase file name including the file extension,\nLANG is the markup code block language for the code's language, and CODE is the code:\n\nFILENAME\n```LANG\nCODE\n```\n\nPlease note that the code should be fully functional. No placeholders.\n\nYou will start with the \"entrypoint\" file, then go to the ones that are imported by that file, and so on.\nFollow a language and framework appropriate best practice file naming convention.\nMake sure that files contain all imports, types etc. The code should be fully functional. Make sure that code in different files are compatible with each other.\nBefore you finish, double check that all parts of the architecture is present in the files.\n"

}

]

Challenges

After going through key ideas and demos of building LLM-centered agents, I start to see a couple common limitations:

-

Finite context length: The restricted context capacity limits the inclusion of historical information, detailed instructions, API call context, and responses. The design of the system has to work with this limited communication bandwidth, while mechanisms like self-reflection to learn from past mistakes would benefit a lot from long or infinite context windows. Although vector stores and retrieval can provide access to a larger knowledge pool, their representation power is not as powerful as full attention.

-

Challenges in long-term planning and task decomposition: Planning over a lengthy history and effectively exploring the solution space remain challenging. LLMs struggle to adjust plans when faced with unexpected errors, making them less robust compared to humans who learn from trial and error.

-

Reliability of natural language interface: Current agent system relies on natural language as an interface between LLMs and external components such as memory and tools. However, the reliability of model outputs is questionable, as LLMs may make formatting errors and occasionally exhibit rebellious behavior (e.g. refuse to follow an instruction). Consequently, much of the agent demo code focuses on parsing model output.

Citation

Cited as:

Weng, Lilian. (Jun 2023). “LLM-powered Autonomous Agents”. Lil’Log. https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2023-06-23-agent/.

Or

@article{weng2023agent,

title = "LLM-powered Autonomous Agents",

author = "Weng, Lilian",

journal = "lilianweng.github.io",

year = "2023",

month = "Jun",

url = "https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2023-06-23-agent/"

}

References

[1] Wei et al. “Chain of thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models.” NeurIPS 2022

[2] Yao et al. “Tree of Thoughts: Dliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10601 (2023).

[3] Liu et al. “Chain of Hindsight Aligns Language Models with Feedback “ arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02676 (2023).

[4] Liu et al. “LLM+P: Empowering Large Language Models with Optimal Planning Proficiency” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.11477 (2023).

[5] Yao et al. “ReAct: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models.” ICLR 2023.

[6] Google Blog. “Announcing ScaNN: Efficient Vector Similarity Search” July 28, 2020.

[7] https://chat.openai.com/share/46ff149e-a4c7-4dd7-a800-fc4a642ea389

[8] Shinn & Labash. “Reflexion: an autonomous agent with dynamic memory and self-reflection” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.11366 (2023).

[9] Laskin et al. “In-context Reinforcement Learning with Algorithm Distillation” ICLR 2023.

[10] Karpas et al. “MRKL Systems A modular, neuro-symbolic architecture that combines large language models, external knowledge sources and discrete reasoning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.00445 (2022).

[11] Nakano et al. “Webgpt: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.09332 (2021).

[12] Parisi et al. “TALM: Tool Augmented Language Models”

[13] Schick et al. “Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04761 (2023).

[14] Weaviate Blog. Why is Vector Search so fast? Sep 13, 2022.

[15] Li et al. “API-Bank: A Benchmark for Tool-Augmented LLMs” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.08244 (2023).

[16] Shen et al. “HuggingGPT: Solving AI Tasks with ChatGPT and its Friends in HuggingFace” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17580 (2023).

[17] Bran et al. “ChemCrow: Augmenting large-language models with chemistry tools.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.05376 (2023).

[18] Boiko et al. “Emergent autonomous scientific research capabilities of large language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.05332 (2023).

[19] Joon Sung Park, et al. “Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03442 (2023).

[20] AutoGPT. https://github.com/Significant-Gravitas/Auto-GPT

[21] GPT-Engineer. https://github.com/AntonOsika/gpt-engineer